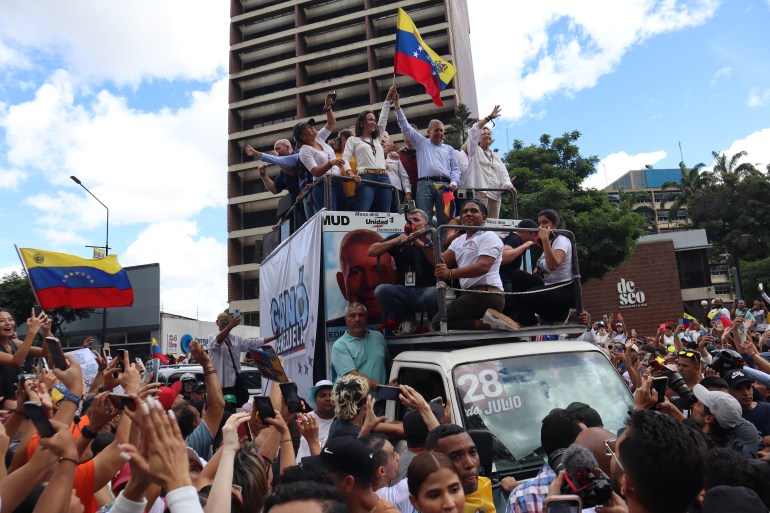

Caracas, Venezuela – A mini-truck — with its cargo bed set up like a small stage — paraded through the streets of Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, on Tuesday. It was emblazoned with a simple phrase: “He won.”

That truck carried opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia, one of two people claiming victory in Sunday’s presidential election.

But on the other side of town, that same day, a government rally was telling a different version of events.

There, the incumbent Nicolas Maduro appeared on the balcony of the Miraflores presidential palace to thank his supporters for propelling him to re-election. They joined him in a rendition of the national anthem.

Both sides maintained they had triumphed. But their celebrations were overshadowed as waves of protest and repression gripped the country.

Venezuela’s attorney general, a Maduro ally, announced on Tuesday that 749 “criminals” had been arrested during the demonstrations, on charges ranging from terrorism to obstructing public roadways.

The human rights group Foro Penal estimated that 11 people had been killed as of Wednesday.

Experts say the violent reaction from the Maduro government is an attempt to quash the opposition — and impose its desired election results.

“Maduro is trying to solidify the reality of this scam,” said Ryan Berg, director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Through repression, Berg explained, Maduro aims to “ensure that this fake, fabricated result becomes the facts on the ground”.

Two candidates, two results

Outrage over the contested election began in the early hours of Monday, when Venezuela’s National Electoral Council (CNE) — an institution controlled by government loyalists — announced that Maduro had prevailed.

It awarded 51 percent of the vote to Maduro, versus only 44 percent for Gonzalez.

But immediately, those results aroused suspicion. Public opinion polls in the lead-up to the vote suggested Gonzalez had a staggering lead: The firm ORC Consultores, for example, found that Maduro trailed Gonzalez by 47 percentage points.

Then there were questions about the vote tally itself. The CNE did not release its usual breakdown of the votes from each polling station, as it had done in the past.

Amid the confusion, the opposition, led by Gonzalez and Maria Corina Machado, accused the Maduro government of manipulating the results.

In the days after the vote, Gonzalez and Machado also announced they had access to more than 80 percent of the tally sheets from the nearly 30,000 voting machines used in the election.

Those results, they said, proved Gonzalez was the winner, with 67 percent of the vote compared with Maduro’s 30 percent.

If true, that would make Gonzalez’s win the biggest in more than 70 years — matched only by Maduro’s claims to victory in 2018, in another race marred by allegations of fraud.

Maduro, however, has called the opposition’s claims tantamount to attempting to overthrow the government.

“An attempt is being made to impose a coup d’etat in Venezuela again of a fascist and counterrevolutionary nature,” Maduro said on state TV.

His attorney general has threatened to issue arrest orders for both Machado and Gonzalez. Already, armed forces seized a key opposition leader, Freddy Superlano of the Voluntad Popular party, on Tuesday morning.

Maduro himself has since pledged to release the full vote tally from Sunday’s race, though no timetable has been set — and critics fear the government cannot be trusted to report the results faithfully.

Opposition in uproar

The turmoil has driven opposition supporters to the streets to denounce what they consider massive electoral fraud.

Cristian Jose Camacaro Guevara, a 23-year-old designer, is among them. He lives in Petare, an impoverished suburb in the greater Caracas area.

On Tuesday, Camacaro walked more than five kilometres to the upscale neighbourhood of Chacao to support the pro-opposition protests.

But when he arrived, forces backing Maduro’s government deployed tear gas to disperse the crowds, leaving him and others choking for air.

“You feel strangled. Sometimes you even want to rip off your own skin,” Camacaro explained. He brought a small bottle of water and baking soda from home to rinse his burning face.

Smoke still lingered approximately 200 metres from where he stood as he spoke to Al Jazeera.

Camacaro added that government security forces were not the only threat facing the protesters. He said he saw clashes between demonstrators and “colectivos” — armed paramilitary groups that support the government, often through violence.

“They are armed and we’re not,” Camacaro explained. Some protesters were arrested, he added. “Some even died.”

Camacaro expressed ambivalence towards the opposition: He said he is unsure whether he agrees with the coalition’s political agenda.

But with Venezuela’s economy continuing to flounder and political repression ongoing, he believes that a change in government is necessary.

According to the United Nations, more than 7.7 million people have left the country since 2014, fleeing instability and shortages of basic necessities like food and medicine.

And more may still leave as a result of the elections. In May, a poll from the firm Encuestadora Meganalisis asked voters if they would think about migrating away if there was no change in government.

More than 41 percent said yes. Another 45 percent said they did not know.

Camacaro’s family is among those considering a departure. He said his parents and younger sister have plans to leave next year if Venezuela’s situation does not improve.

“They just cannot take it any more,” he said. He added that they see Sunday’s election and the opposition’s efforts as “the last chance“ for a better Venezuela.

Controversy ‘not over’

In the weeks ahead, Maduro is likely to double down on repression, according to Mercedes De Freitas, founder and director of Transparencia Venezuela, a corruption watchdog.

“I don’t see this as a pacific process. I see lots of tension,” De Freitas said.

In this post-election period, to achieve its aims, “the government needs to show that it has power to repress, do harm and control,” De Freitas added.

Berg from the Center for Strategic and International Studies likewise fears that Venezuela is entering a particularly dangerous period.

International observers are starting to leave Venezuela after the election. And the international community is divided over whether to recognise Maduro’s claims to victory.

On Wednesday, for instance, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador held a news conference saying there was “no evidence” of election fraud in the official tally.

He also called the Organization of American States — which conducts election oversight — “biased”. The organisation had previously voiced concern that there was a “coordinated strategy” to “undermine the integrity of the electoral process” in Venezuela.

The Carter Center, one of the few organisations Maduro allowed to observe the elections, also offered a harsh rebuke to the government. It blamed the Venezuelan authorities for a “complete lack of transparency”.

“This is certainly not over by any means,” Berg told Al Jazeera.