Clockwise from left: A barn owl sits in its cage; a poster of owls; Olivia Miseroy, regional park superintendent, holds an animal ambassador barn owl named Ghost.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

As I turned the corner around a walled-off enclosure at a nature center in San Dimas, I didn’t anticipate all the intense, yellow eyes that would meet me on the other side.

At least 22 great horned owls were staring at me — or, more accurately, through me. One of them was hissing. Out hiking, I often spot great horned owls, usually hearing their unmistakable call long before I spot them high in a tree. Seeing that many owls all at once perched in a 50-foot flight cage outside a county building was remarkable.

I was lucky enough to do so because, on Saturday, Los Angeles County launched its raptor rescue center at the San Dimas Canyon Nature Center. The space is a collection of enclosures: a large one where the owls have enough space to fly, and other smaller spaces for additional birds of prey (including separate areas for those that hunt one another). The county plans to build another 50-foot flight cage in a nearby field for raptors, thanks to $200,000 it received from Supervisor Kathryn Barger’s office.

Staff and volunteers care for the birds, who are often found in nature hurt, sick or without their caretaker. L.A. County Parks and Recreation officials opened the center to fill a tremendous need.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger, left, and Kristine Koh, rehabilitation manager, hold a red-tailed hawk that they released during the grand opening of a raptor rescue center in San Dimas on Saturday.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“We can’t rehabilitate land, we can’t plant new trees and then not look at the sky and also support our birds of prey,” said Norma Edith García-Gonzalez, county parks director.

Before this center, L.A. County partnered with bird rescue Wild Wings of California to look after raptors in need. The nonprofit was shut down by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in 2023, meaning there was only one licensed raptor rescue, in Calabasas, for all of L.A. County.

But people kept calling the San Dimas Canyon Nature Center, asking where to take their birds, and officials realized they had to step up, said Noemi Navar, a regional park superintendent who oversees the center and adjacent park.

Jennyfer Murillo, park aid with San Dimas Canyon Natural Area and Nature Center, cools off Lozen, a red-tailed hawk and animal ambassador.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

The center anticipates, based on its work with Wild Wings, that it will take in 250 raptors — including owls, hawks, kestrels — every year. It will be busiest in the spring during what Navar calls “baby season,” when it will take in dozens of great horned owlets who have been found starving and need to be nursed back to health before being released.

At its launch, the center already had about 70 birds in rehab. Raptors are brought in for several reasons. They might be suffering from infections or injuries or starvation. Maybe they were harmed during severe weather. In some cases they’ve been hurt by humans.

In previous years working with Wild Wings, the center saw birds of prey injured from hitting windows; hit by vehicles; shot by pellet or BB guns; sickened by pesticides or rat poison; or stuck in glue traps, barbed wire or fishing line. Birds are also frequently injured when their nests are destroyed by tree-trimming crews, Navar said.

The grand opening of the raptor rescue center in San Dimas Canyon Nature Center.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Kristine Koh, rehabilitation manager, holds a red-tailed hawk that was later released at the rescue center’s grand opening.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In the past five years, the L.A. County Department of Animal Care and Control impounded more than 1,200 sick or injured raptors, said department Director Marcia Mayeda. Her team will now work with the county’s raptor center to bring injured birds to them, providing 24/7 coverage to rescue raptors.

“As humans encroach on the native habitats, the number of injured and orphaned raptors increases, and rehabilitating them fulfills our ethical duties to mitigate harm caused by human activities and to promote wildlife welfare,” Mayeda said.

Want to get involved? The center just so happens to be in need of volunteers. Helping out involves working with great horned owls, red-tailed hawks, red-shouldered hawks and Cooper’s hawks. Occasionally, Navar says, the center will see a kestrel or screech owl.

When a baby bird comes in, center staff and volunteers find out where the bird came from so they know where to take the fledgling back to its home territory post-recovery. The bird is isolated and evaluated by trained staff and veterinarians. Once cleared, it joins its new pals in an enclosure or cage.

Some have mites and need to be sprayed with treatments. “Others are just little, and we have to feed them, and they have to learn how to feed on their own,” Navar said.

The center starts the young birds off with frozen rats. From there, staff and volunteers work up to releasing live rats in the pen, watching from a distance to make sure the birds can catch their dinner.

“They are wildlife, and it’s extremely important that they stay wild, and that we’re doing our part to stay out of their way, out of sight,” Navar said.

Displays set up during the grand opening of the raptor rescue center.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Of all the birds of prey that come through the center, great horned owlets take the longest to raise before release: five months. It costs $3 per rat to feed them, and the birds get at least one rat per day. In total, that adds up to about $900 per owl. To supplement the cost of their meals, the county’s foundation has launched a fundraising campaign to support the center.

Becoming a volunteer at the center is no easy feat. First, after completing a background check, you’ll take the 11-week docent course. Next, you will volunteer at the nature center, helping with outreach, tours, cleaning and prepping the raptors’ food. You’ll also take a written and practical exam. After 500 hours of training, you’ll be ready to join the team in all volunteer tasks.

“This is a lot of work all the time,” Navar said. “So, as long as somebody is committed to come and work with us and volunteer, we are happy to take as many that are willing to give their time.”

But if you have an open schedule and open mind, Laura Dugan with the Pomona Valley Audubon Society said at Saturday’s launch that your volunteering hours will have a real impact in the local ecosystem.

Visitors watch a red-tailed hawk soar to freedom in San Dimas on Saturday.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“Each bird that soars back into the skies represents not just a triumph of rehabilitation, patience and compassion, but also a step toward restoring the natural balance of our ecosystems,” Dugan said. “And studies show that rehabilitation works — banded rehabilitated birds have been recorded successfully breeding for many years after release.”

To learn more about volunteering, visit parks.lacounty.gov. Let me know if you sign up!

Newsletter

You are reading The Wild newsletter

Sign up to get expert tips on the best of Southern California’s beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains in your inbox every Thursday

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

3 things to do

Guests enjoy wine and friendship at the Barnsdall Art Park Foundation’s weekly wine tasting.

(Photo by Janna Ireland; from Barnsdall Art Park Foundation)

Sip wine with friends at Barnsdall Art Park in L.A.

Grab your picnic blanket and pals, and head over to Barnsdall Art Park in L.A. for the park foundation’s Friday night wine tastings. You will sip vino curated by local Silverlake Wine amid backdrops of the Hollyhock House, which is available for touring for an extra fee, and stunning views of the Hollywood sign and Griffith Observatory. You can also purchase dinner from food trucks on site. Tickets are $47.75, or $16.25 for designated drivers. Proceeds support park programming. The event starts at 5:30 p.m. and runs every Friday until August 30. Learn more at barnsdall.org.

Kayak through Upper Newport Bay in Newport Beach

Enjoy the wonders of Upper Newport Bay, one of the largest remaining estuaries in Southern California, via a two-hour kayaking excursion hosted by the Newport Bay Conservancy. A naturalist leads the tour through this area of nearly 1,000 acres of wetlands. Nearly 200 species of birds have been spotted in the wetlands, including the endangered California least tern. Lucky paddlers might spot a silver mullet — a fish, not a cool grandpa — or even notice a stingray glide beneath their boat. Find tickets at eventbrite.com.

Volunteer at a cleanup at the Whittier Narrows Nature Center in South El Monte

The Whittier Narrows Natural Area is a gem of an L.A. County park, offering 400 acres of riparian woodlands. On Saturday, you can volunteer from 8 a.m. to noon to help clean the area around the Whittier Narrows Nature Center. You’ll pull weeds, sweep, pick up litter, bag leaves and rake. And probably make some friends! Wear a long-sleeved shirt, pants, hat and closed-toe shoes. Sunscreen is also recommended. Learn more on the county parks department’s Instagram page.

The must-read

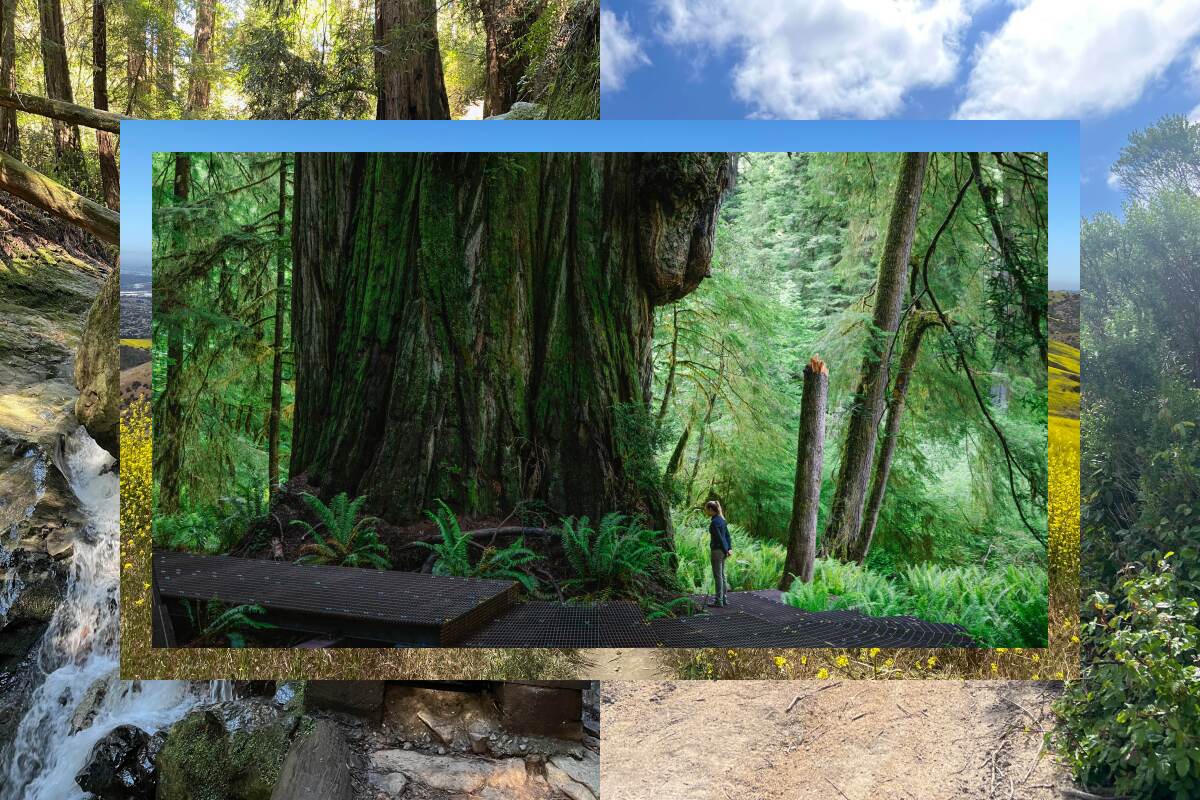

California’s state parks boast thousands of miles of trail.

(Photos by Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times and John McKinney)

Can you list five of California’s state parks? Most residents cannot, writes outdoors journalist John McKinney, in this guide to 10 magnificent hikes in some of California’s state parks. His list includes Mt. San Jacinto State Park, where you can take the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway to hike from Mountain Station (8,516 feet) to the summit of Mt. San Jacinto (10,834 feet). “Imagine hiking in Switzerland while gazing down at the Sahara,” McKinney wrote of the view from this peak near charming Idyllwild.

More than 100 of California’s state parks offer nature walks, family hikes and all-day adventures on about 3,000 miles of trail. This piece will help you tick some of those miles off your must-hike list.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Sometimes when I start a hike, I wonder to myself how at risk I am that day of a sunburn — especially if I’ve forgotten to apply sunscreen.

Thanks to the fine folks at Joshua Tree National Park, I recently learned “the shadow rule.” Turns out, if your shadow is taller than you, you will experience less UV exposure. If your shadow is a short little guy, then you have higher UV exposure, and thus are at higher risk of getting burned. Short shadow, high risk. Got it!

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.