The Zodiac killer struck first. Then came the Manson family. Later, the Hillside Stranglers, the Night Stalker and the Golden State Killer terrorized California.

Starting in the late 1960s, one lurid murder after another fed public perceptions that crime in California was spiraling out of control. Gang shootings turned neighborhoods into combat zones. The crack epidemic ravaged communities.

Fear and outrage spawned a raft of harsh sentencing laws. California enacted one of its most punitive, “three strikes and you’re out,” after one parolee killed 18-year-old Kimber Reynolds of Fresno in 1992 and another kidnapped and killed 12-year-old Polly Klaas of Sonoma County a year later.

“We’re going to start turning career criminals into career inmates,” Republican Gov. Pete Wilson declared in 1994.

The laws strengthening criminal penalties drove a surge in the state’s prison population over 30 years, beginning in the 1970s. Under both Republicans and Democrats — including Kamala Harris, who became a prosecutor in 1990 — a tough-on-crime political culture flourished in California, and African Americans were hit hardest: Their incarceration rate remains more than five times their share of California’s population.

The crackdown on crime swept most of the country, but California stood out as one of the most aggressive states. Only recently has it begun shedding its lock-’em-up mind-set.

In the 2020 presidential race, the disproportionate imprisonment of African American men has become a major issue, and it’s posing an especially big challenge for Harris, California’s first black U.S. senator. She is counting on strong support from African Americans. But many black voters are wary of her 27 years as a prosecutor enforcing laws that sent African Americans to prison.

Often left unsaid is that Harris, a former state attorney general and San Francisco district attorney, did not play a role in passing those laws.

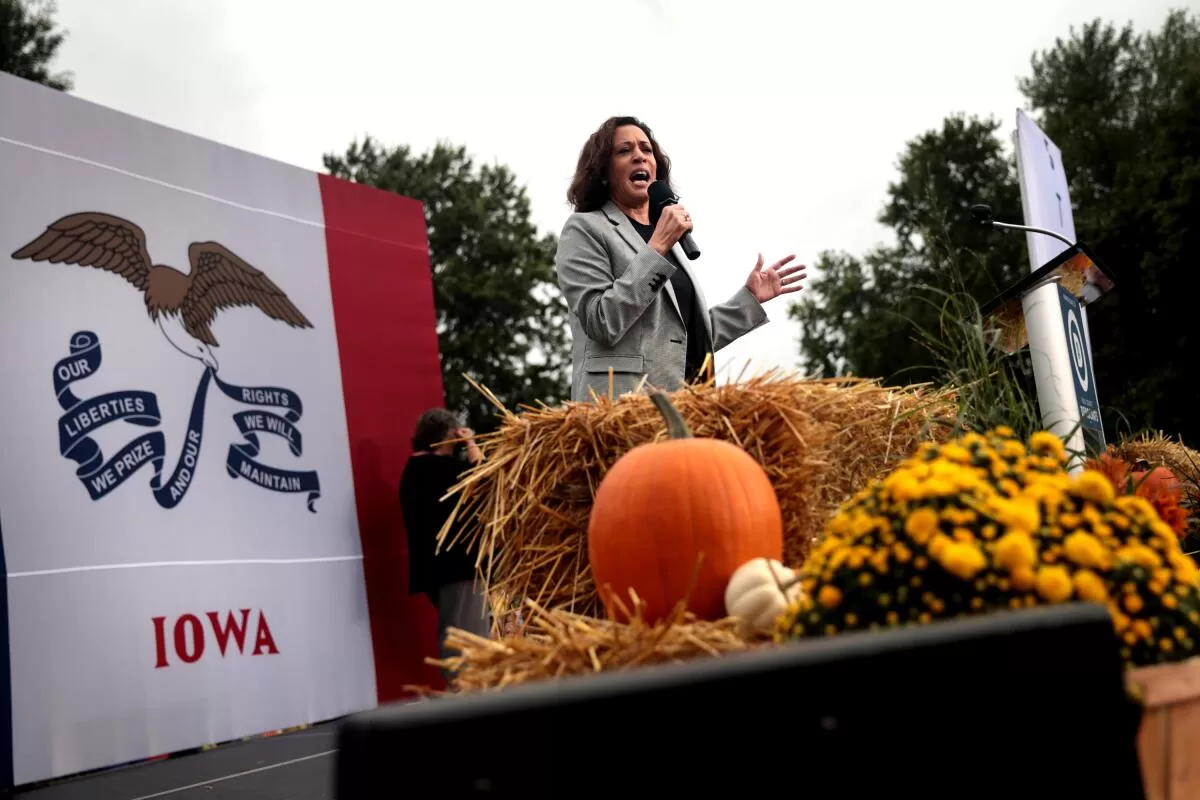

Kamala Harris campaigns in Des Moines. Many black voters are wary of her years spent enforcing laws that sent African Americans to prison.

(Scott Olson / Getty Images)

Still, her home state’s high rate of incarcerating people of color goes a long way in explaining the trouble she has had selling her candidacy to black voters nationwide. In California and many other states, racial disparities in imprisonment have intensified resentments of what many see as deeply ingrained discrimination in America’s criminal justice system.

“Communities of color, they have a hard time trusting you when you are connected with law enforcement,” said Yvette McDowell, a black attorney and former Pasadena prosecutor who is undecided in the Democratic presidential race.

Citing generations of racial bias in the justice system, banks and other institutions, she said, “History has taught us a lot about distrusting people who don’t have our best interests at heart.”

Tensions between law enforcement and California’s black communities run deep. The 1965 Watts riots stemmed largely from anger over police brutality. The Black Panther Party, formed the following year, set up patrols to monitor police harassment in Oakland. The L.A. riots of 1992 were touched off by the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of Rodney King, an African American.

The friction with law enforcement has had a broad cultural impact. In the 1980s and 1990s, black outrage at police misconduct was a frequent theme in the music of Tupac Shakur, N.W.A. and other West Coast rap performers. Ice Cube, the former N.W.A member who wrote the lyrics to “F— the Police,” told The Times in 1989 that cops “see you in a car” and “assume you are a dope dealer.”

Black outrage at police misconduct was a frequent theme in the music of West Coast rap performers like Ice Cube.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

The United States now has the world’s highest incarceration rate, with 2.3 million people in jail or prison.

“You have this multi-generational impact of the absence of 2 million people, and the people who come home — not rehabilitated, just punished — can’t get housing and jobs,” said Karim Webb, an L.A. restaurant owner active in promoting young entrepreneurs affected by racial bias in the justice system.

“It has led to a miserable set of circumstances for people to have to try to overcome with very, very limited tools or resources.”

(Chris Keller / Los Angeles Times)

Many of the crimes that set in motion California’s prison boom were ghastly. The theatrically named serial killers left scores of victims and a trail of mayhem that both captivated and terrified the state.

Jonathan Simon, author of “Mass Incarceration on Trial,” sees the 1969 murder of nine people by members of the Charles Manson cult as the “turning point in building public consensus that violent crime in California was really out of control and nobody was safe from it.”

In 1976, Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, signed a package of crime bills mandating stiffer punishments. They abolished most of California’s indeterminate-sentencing laws, requiring most felons to serve fixed prison terms. The idea was to crack down on crime and curb racial prejudice in parole board decisions on the release of inmates.

In 1976, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a package of crime bills mandating stiffer punishments.

(Jeff Robbins / Associated Press)

Liberals feared lawmakers would keep toughening penalties, leading to overcrowded prisons. That’s indeed what happened under Republican Govs. George Deukmejian and Wilson and Democratic Gov. Gray Davis.

“Every news story of an atrocious crime generated a bill saying, let’s add five years to that,” recalled former state Atty. Gen. Bill Lockyer, a Democrat who served in the Legislature from 1973 to 1998.

The peak of the tough-on-crime era was 1994, when Wilson signed the “three strikes” law, a move ratified by voters months later. For anyone convicted of a serious felony, the penalty was doubled for a second such crime, and for a third it was 25 years to life in prison.

The measure’s highest-profile sponsor was Mike Reynolds, the grief-stricken father of Kimber, who was shot in the head and killed in 1992 in a Fresno purse robbery. Then in 1993, another parolee kidnapped Polly Klaas from a slumber party and strangled her.

Both crimes “just crystallized public opinion around ‘we need to do something,’ ” recalled Rose Kapolczynski, a top campaign advisor to Barbara Boxer, Harris’ predecessor in the Senate.

Violent crime was declining from its 1991 peak when California became one of a dozen states that passed three-strikes laws in 1994. That was the same year President Clinton signed a crime bill that many Democrats now see as overly punitive.

(Chris Keller / Los Angeles Times)

“In retrospect, it had a lot of unintended consequences, but at the time it was definitely part of the effort to reframe the debate around crime and undercut Republicans who just painted every Democrat as putting your family’s life in danger,” Kapolczynski said.

The consequences in California’s prisons were dramatic. From 1977 to 2006, the population jumped from fewer than 20,000 inmates to over 166,000 — more than double the prison design capacity. Since 1984, California has spent $6.2 billion building 23 prisons.

California’s prison overcrowding got so severe that the U.S. Supreme Court found in 2011 that unsafe and unsanitary conditions had caused “needless suffering and death,” a breach of the Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Through ballot measures and legislation, California has reduced the number of inmates and pared back prison sentences mandated under its three-strikes and other criminal laws.

But the prisons remain emblematic of chronic racial inequities in the justice system. African Americans make up less than 6% of California’s population but 29% of its inmates, according to the state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Latinos are 39% of the population but 43% of the inmates.

By contrast, whites are 37% of California’s population but just 22% of the state’s prisoners.

(Chris Keller / Los Angeles Times)

In California and other states, prison “became a seemingly normal part of the life cycle in low-income communities of color,” said Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that works to stop mass incarceration.

In many black communities, he said, police “stop and frisk” practices further eroded public trust of law enforcement, as did the spread of phone videos showing officers shooting and killing unarmed African Americans.

“Confidence in the police as an ally in promoting public safety — whatever challenges there were already I think were greatly magnified,” Mauer said.

In her campaign for president, Harris has vowed to relieve mass incarceration and correct racial inequities in the justice system. As attorney general, she started implicit-bias training for law enforcement, and as district attorney she launched a program that enabled first-time nonviolent offenders to get their charges dismissed if they finished job training.

Critics have faulted her, though, for working in court to uphold California’s death penalty, despite her personal opposition, and for her threats to jail parents of chronically truant schoolchildren.

Zachary Norris, executive director of the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, an Oakland group that works to shift public resources from prisons to community investments, said police intimidation and mass incarceration drag families and neighborhoods “into a cycle of debt and deprivation.” As a result, he suggested, Harris and any other former prosecutor running for high office must clear a substantial hurdle to gain black support.

“When you have folks who are seen as the face of moving young people and adults into that system, there is going to be a residue of anxiety, a residue of unfairness,” Norris said. “Someone whose main position has been to be a part of that process, I think, is going to be in a very difficult position.”