A great crime novel doesn’t just tell a story of wrongdoers being forced to answer for their misdeeds. It doesn’t stop at the whodunit aspect or the terse repartee between jaded cops, but rather it says something about the world in which the injustice takes place.

That’s a key element in the work of Attica Locke, a novelist and television writer and producer, whose Highway 59 book trilogy follows a Black lawman named Darren Mathews as he confronts the horrors of racial prejudice in contemporary East Texas. In the series’ upcoming finale, “Guide Me Home,” Mathews comes out of his early retirement to look into the disappearance of a Black college student in an all-white sorority.

“Every novel is a crime novel,” Locke told me last week. “It’s a crime of the heart. It’s a moral crime. It is a crime to me the way in which our government is not taking care of its citizens.”

Locke has blazed an unusual path for herself.

After toiling for years as a screenwriter for hire in Hollywood, she turned to fiction writing, publishing her first novel, “Black Water Rising,” in 2009.

Since then, she’s found success in TV, with credits on Fox’s “Empire,” Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us” and Hulu’s “Little Fires Everywhere,” adapted from Celeste Ng’s novel. In 2022, she brought her own sister Tembi’s memoir, “From Scratch,” to the screen for Netflix. Locke is currently developing her first Mathews novel, “Bluebird, Bluebird,” for Universal Television, where she and her sister have an overall deal.

I spoke with Locke earlier this year at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books for a panel discussion on book adaptations. Last week, I caught up with her to revisit her thoughts on her career, the craft of writing and the challenges of working in today’s television business environment.

“Guide Me Home” author Attica Locke.

(Victoria Will)

The new novel is deeply political, addressing directly how many Black Americans felt in the wake of the Trump election in 2016. Why did you want to address that atmosphere through the story of this Texas lawman?

It was, in some ways, an accident, meaning I wanted to write about Highway 59 because I’m from that area and I spent a lot of my childhood riding up and down, visiting relatives. And I had this idea to do this book series in which each book would be a different little rural town along this highway. And when I talked to both my agent and a publisher, I had to think about who would be the main character. Is it a lawyer? A PI? And when I thought of Texas Rangers, I thought, “Well, there’s the answer.”

So I was like, “What do they do?” One of the big things they had been doing was that they had a task force looking at the Aryan Brotherhood, but really as a gang that was running drugs and guns, not the moral issue of what the group meant to me as a Black person. So I just folded that into the book, having absolutely no idea that Donald Trump would be elected. I couldn’t just somehow erase the fact that I had written myself into this world, and I simply leaned into it. I allowed it to give me the gift of a space to work through my own feelings about the world shifting in this particular moment.

And that very much continues in your new book, “Guide Me Home.”

The politics, specifically with this book, scared the crap out of me, only because I thought people don’t want that. This book in the series has a very different energy. And I was scared that it wasn’t following the tropes of the genre in the way that it should. My husband read it and said, “You know what I see here? It’s like you’ve got a protagonist who wants out of the genre.”

There’s no way to ignore where we are, not with a thinking character like this. For me, this is the way the series had to end. But I have been a little scared that readers will be like, “What?” because it moves at a different pace. It’s asking about crimes that aren’t shoot-em-up, bang-bang crimes.

You started your career as a screenwriter, right?

I was going to be a director. That’s what I thought I wanted to do. I did the Sundance Labs in 1999 — oh, my God, another lifetime ago. I came out of there with a movie deal that just never went forward for a multitude of reasons. There were concerns about raising foreign financing with Black rural material. And I just kind of went, “What am I going to do?”

In my heart of hearts, I don’t think I’m a director; I’m a storyteller. So I ended up being a professional screenwriter for hire for well over a decade, because I had to eat. What’s funny is, I was at Sundance with a script — a version of “Bluebird, Bluebird” that didn’t have a ranger — and it just never went anywhere. I would think about it every now and then, that I could always resurrect this as a book.

Now it’s come full circle and you’re adapting “Bluebird, Bluebird” for Universal. How did that opportunity come about?

After my sister and I made “From Scratch,” we took meetings all over town looking at who we might partner with for a more long-term relationship. And Universal just loved the book series.

What’s interesting about now having a partner in my sister is that she sees things in my own book that I’m not thinking of. And with the adaptation, you have to bring something new. It’s such a tricky thing to catch the soul of a book in a bottle. What you’re trying to do is, “What did it feel like when I put that book down?” I’m chasing that feeling over eight episodes. And when I was able to see that there were new things that I could bring to Darren Mathews’ story, then I got excited. Honestly, if we don’t have anything new to say, there’s not really a reason to do it.

It sounds like you took a lot of lessons from having adapted other people’s works, including “Little Fires Everywhere” and even your own sister’s memoir (“From Scratch”). What did you learn from that experience?

[Making “From Scratch”] was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. It was just weird, but also magical. I think the gift that it gave me was that it kind of grew me up in a way. I really learned a lot about the beauty of elegant conflict. When Tembi and I would be in conflict, we were safe to get uncomfortable because we all loved each other at the end. My sister was very clear about what her non-negotiables were and what could never get cut from the story. And once I knew what was most important to her, then you get to play.

When adapting your own work, do you come in with non-negotiables for yourself and the studio?

It’s funny, because I haven’t said what those are out loud yet. Here’s the other great thing, especially about having been the author: What I wrote is on a shelf; it will never ever, ever be undone. Now you’ve got me thinking I should go home and write down my non-negotiables.

Here’s another instance where I’m working with my sister. She doesn’t have the same feelings about Texas that I do, but she knows me. So there’s this weird thing where there’s some things that almost don’t need to be said.

Since your background is as a professional screenwriter, do you apply some of those cinematic ideas to your fiction writing? Do you think in terms of set pieces?

I don’t, but I do think what is similar is that I’m writing what I see. When I was writing my debut novel, I was putting on a kind of literary air in the way I was writing sentences. It didn’t sound quite like me, and my husband was like, “I get what you’re doing here but I don’t think it works.” And one night, I was reading a Pete Dexter novel that was in the present tense. And I was like, “That’s my mother tongue.”

I remember getting up out of bed and going downstairs and rewriting the first few pages of the novel in the present tense. It was like I was suddenly freed. I found my own voice because I was connecting up to the screenwriter in me, where I wasn’t needing to pretend to be a different type of writer.

We get a lot of Darren’s characterization from getting into his head. Have you thought about how you’ll bring that to the screen from the page?

That’s gonna be the hardest part. He’s a conflicted man, and he’s a fundamentally moral man, and I think you can write into that feeling state, rather than literally having his actual interior thoughts.

At a certain point, you’ll probably have to trust the actor’s ability to convey that.

Yes, and I look forward to getting there. I think we are in a time in our business right now where everyone’s a little on the back foot after 2023, and I feel the trepidation. I feel the need to get everything in order before you green-light or shoot, and that bumps up against the novelist in me.

I’m going to paraphrase from Jane Smiley: Writing is writing; it is not planning. Right now, there’s a lot of, “I don’t want to spend money or buy anything until you tell me everything.” And I understand it. “From Scratch” cost a lot of money. So I totally get people going, “Wait a second.”

Right. We’ve been writing a lot about the industry contraction and how it has affected workers and writers. It seems difficult to be a creative in that environment.

I also think it’s difficult for the executives who are not the owners of these companies and are trying to make things happen. Before, there had been this buoyancy, this kind of lightness. And right now, I feel a heaviness. Joy is an access point to vision, and I’m really missing vision. I have a lot of compassion and understanding for where we are. I just don’t know what the answers are to give everybody that sense of excitement again.

Well, now when studios are looking at intellectual property, they’re not just looking at it in terms of whether it can be a six-episode miniseries. It’s about whether it can also be a pop-up store, a restaurant or a mall feature.

I’m just doing my little, bitty part of it in my little corner to try to still access joy and do the work. My sister Tembi said, “I feel the contraction too. And all we can do is find points of light through the restriction.” Find ways that we can bring people joy and make people think in different ways about the human condition.

Are you sure this is the end of the Highway 59 series? The world is giving you a lot of fresh material to work with.

I will never say never, but like I said, I accidentally wrote myself into a series that became an exploration of the Trump era, and I think there’s some fantasy inside me that if I just stop writing the books, it’ll go away. And I know that’s ridiculous, but I don’t want to write anymore about this time in our history through this particular lens.

Newsletter

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

‘I couldn’t pay the rent anymore’: One of Hollywood’s last costume shops is closing. Legendary costume designer Ursula Boschet has been in business for nearly half a century, but at 90, the combined forces of the pandemic and the Hollywood slowdown have forced her to close up shop.

Willow Bay explains why she and Bob Iger bought Angel City FC. Bay and her husband, the Walt Disney Co. CEO, are investing more than $100 million into the women’s soccer club. “Women’s sports is having a culture-defining moment,” Bay said.

Why some Silicon Valley investors are backing the Trump-Vance campaign. Several prominent tech types are vocally backing Trump due to concerns about how the government is regulating cryptocurrency, its policies on artificial intelligence and the threat of an increase in capital gains taxes.

Disneyland workers vote overwhelmingly to authorize strike. The vote gives union leaders the option to stage a walkout if contract negotiations stall.

‘Bridgerton’, ‘Baby Reindeer’ help boost Netflix earnings. Netflix said it added roughly 8 million subscribers in the second quarter, bringing its membership base to about 278 million globally. Wall Street’s reaction? Meh.

ICYMI

IATSE ratifies new contract

Video game performers inch closer to strike

Warner Bros. Discovery tries to match Amazon NBA bid

Hollywood throws support behind Harris

Two historic L.A. movie theaters close this week

Number of the week

The $80.5-million domestic opening weekend for “Twisters” shows what happens when a studio understands the kind of movie it has and who the audience is.

In this case, the film was big everywhere but really tore it up in the Midwest, which you could kind of tell was going to happen based on the marketing campaign. The ads put Glen Powell in a cowboy hat with a truck-commercial country rock soundtrack. If that’s not a winning formula, I don’t know what is.

Looking at the opening weekend demographics, nearly half the attendees were over 35 and 78% were over 25.

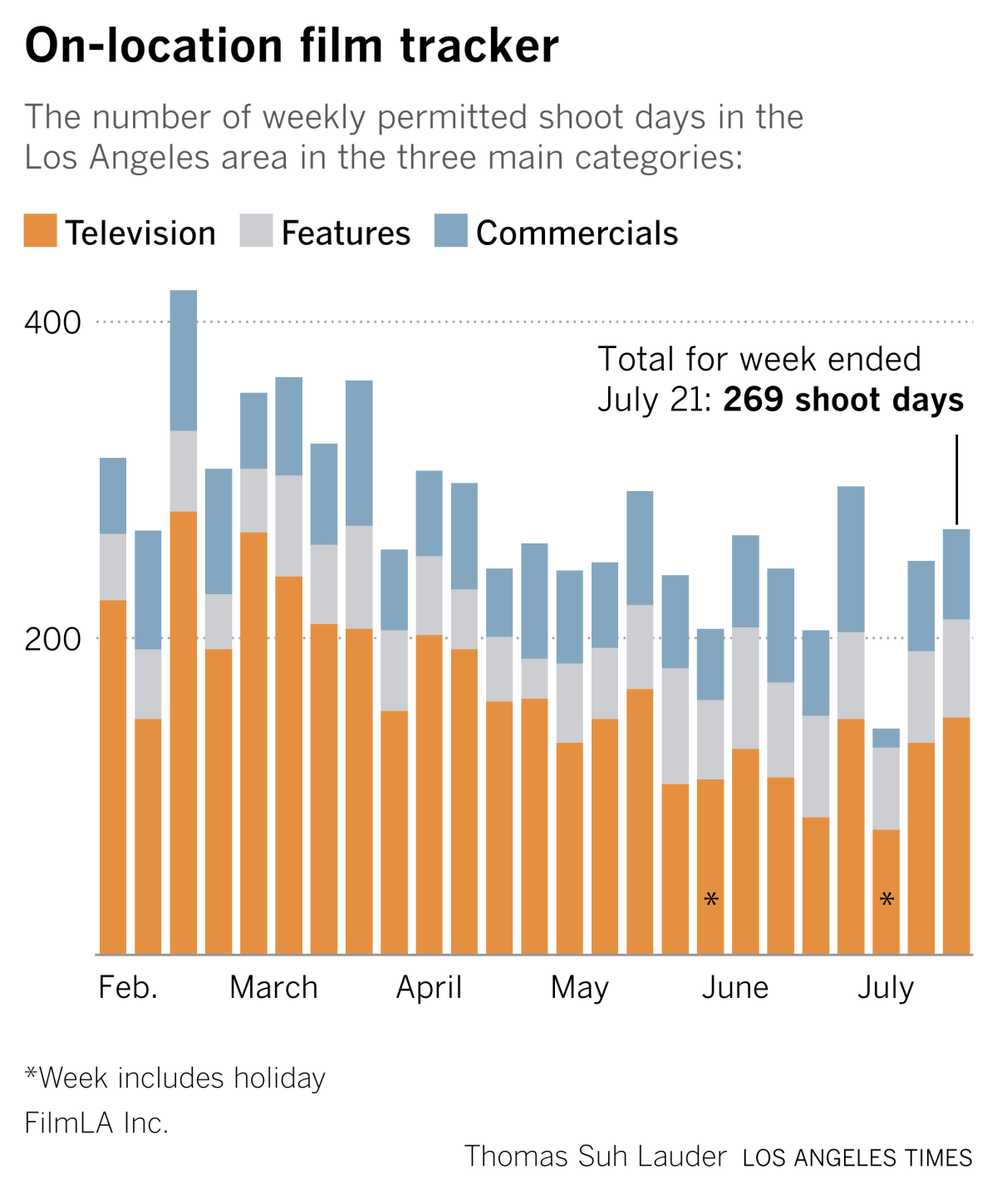

Film shoots

On location production in the Los Angeles area was up last week, according to FilmLA permitting data.

Best of the web

— TikTok’s one-man Telemundo. (New York Times)

— White collar work is just meetings now. (The Atlantic)

— Entertainment and media sales to hit $3.4 trillion in 2028. (Bloomberg)

Finally …

The band Mannequin Pussy put out a new album earlier this year and it rocks.