As far as many residents of southeastern Nigeria are concerned, the vast stretch of interstate borderland between Anambra and Imo state is no man’s land — except for the few who find haven in the area.

Some locals call it Mother Valley due to its steep forest terrain. Some have even named parts of it the Sambisa of the South East — after the infamous stronghold of violent extremists in northeastern Nigeria. The forest area goes by many other names depending on which community you’re in. It spans over 700 hectares and is within reach of thousands of rural populations. On a map, it appears as a vast green spread between border communities. The forest is so dense that most of the ground is invisible from above. It houses wildlife, tall tropical rainforest trees, broad leaves that form a thick canopy over the landscape, and separatist hideouts nestled close to its fringes with communities.

The area provides cover for hideouts used by Pro-Biafran militants, who typically identify with the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a separatist group founded over a decade ago.

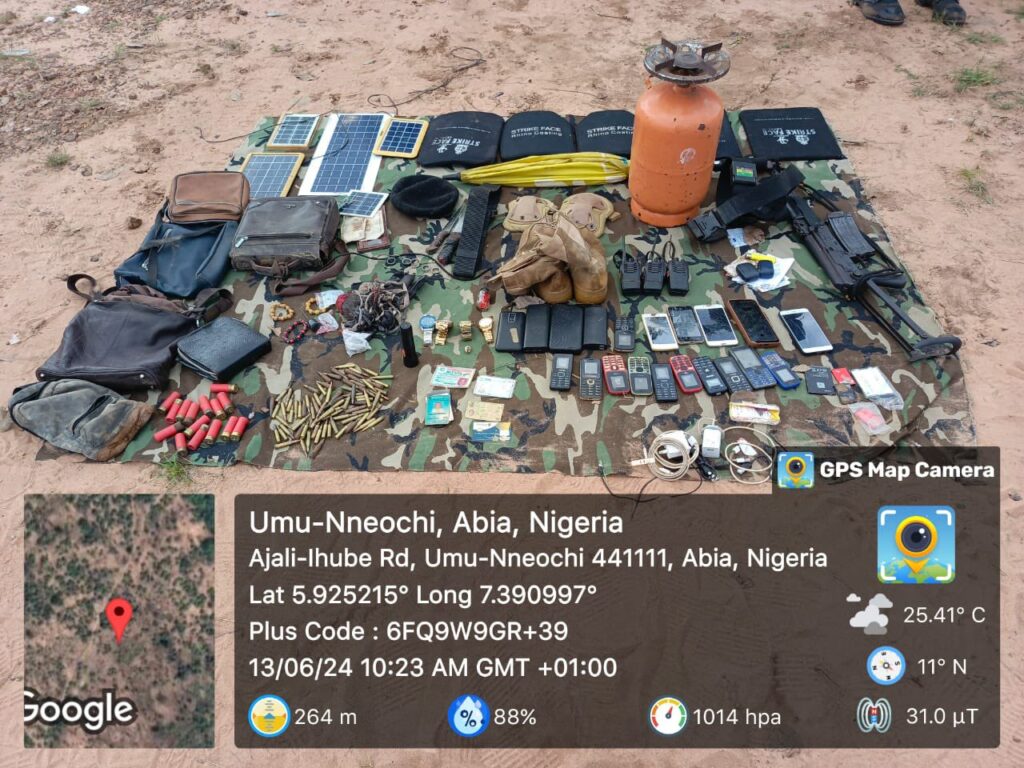

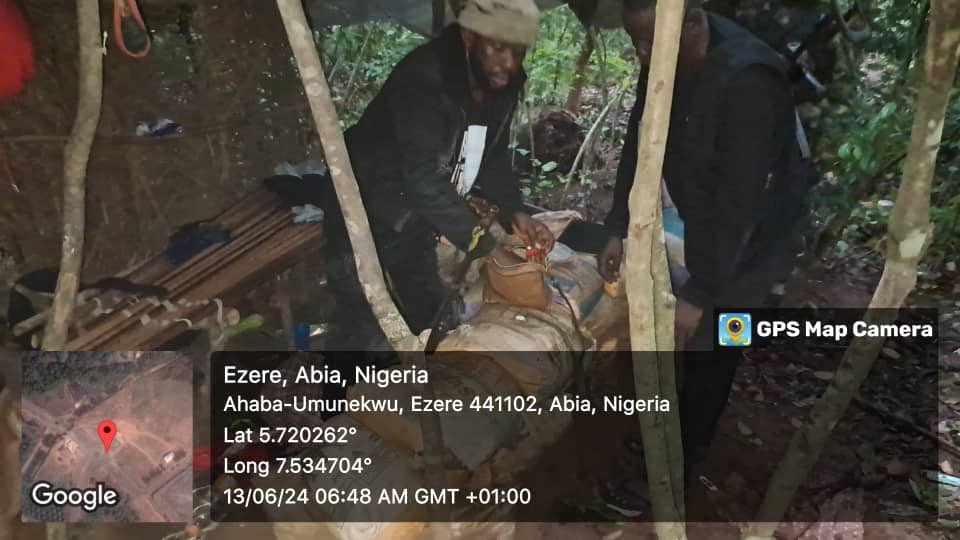

The hideouts vary in size and purpose. Some are small, four-foot-tall tents used to store weapons under the bushes, while others are large campgrounds with domestic supplies and living quarters. One example is the infamous bushes near Orsumoghu town in Imo state. In March 2024, the army conducted an operation in one of the separatist camps there, recovering weapons and various supplies used by IPOB fighters and uncovering the major base of operation, which had eluded the troops for years despite repeated aggression by non-state actors in the area. At some point during the raids early this year, videos circulated of the army allegedly deploying multiple armoured tankers and personnel to secure the area.

“I hope the military leaders will come up with a better strategy. We are tired of Orsumoghu looking like a war zone,” an X/Twitter user said, reacting to the video.

Although some areas in Orsumoghu have been recovered, ongoing operations in the region indicate that more terror enclaves persist within these forests.

Most of the separatist camps in the South East are within walking distance of the communities. Being familiar with these communities enables them to operate from nearby bush camps and blend with townsfolk when inactive. Some confession videos suggest recruitment from these areas. Military operations have located and identified some of these camps with foot soldiers often stationed to guard weapons and abduct victims. Yet many of the hideouts remain elusive.

Sometimes, the camps are not even in the bushes but in the compounds of top commanders who reside in the communities they terrorise.

This tactic blurs the line between violent separatists and townspeople. Sometimes, residents claim they are being profiled as members of IPOB, prompting young men to avoid staying in communities considered as hotspots.

While some of these camps have been found, many remain uncharted by security forces. Various pictures and videos show the camps in the forests of the five southeastern states and sometimes in the South-South. They capture how the insurgents conduct executions and dump bodies in ditches or shallow graves. Occasionally, security forces stumble upon these elusive sites, finding pits of bodies. Other times, the violent groups post clips from unidentified locations showing the decomposing bodies of victims.

The forests in South East Nigeria are dense, with tall tropical palm trees and closely packed bushes that create large covers over the ground. This makes it easy to conceal makeshift tents and secret burial sites.

State forces — including the police, soldiers, and sometimes local security outfits — have conducted numerous operations in these forests. The pattern is almost always the same: follow intelligence to locate an area often situated less than an hour’s walk into the nearest bushes of a rural community being terrorised.

If you were in the B44 camp in Oru, Imo state, you only needed to take a dirt road north of the forest hideout and walk a little before crossing a river. Then, a straight path through the woods awaits. If you are new to the area, you may stop to admire the palm trees, municipal forest, and the houses stylishly embedded within them before coming upon another dirt road. From there, it’s a 20-minute walk to the fringes of the crude oil-producing Awo-Omamma community.

The B44 camp, also called Monday Oluchi Ogu Camp, is well-positioned to enforce the sit-at-home order in the area. The insurgents also terrorise surrounding communities such as Izombe towards the west and possibly Umuaka to the south of the camp and Umunoha a little further south. Members likely comprise locals of the community. They would meet their local native doctor there in Awo-Omamma to prepare charms for them. When these charms failed, they knew where to find him and delivered the same fury they sought for their enemies.

Awo-Omamma is rife with soldiers and police formations, making it a highly contested area between IPOB enforcers and state security teams. At least five major clashes have been documented by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) Project since 2021.

Finally, in March this year, the Nigerian Army invaded the camp, recovering a cache of weapons and other operational resources.

The assumption is that many of these IPOB propaganda videos shot in unidentified locations were filmed in the South East, particularly in Imo state, where they are most active. However, it is hard to know, considering that some have no visual clues to aid image analysis.

The videos sometimes show people being executed and buried or dumped in ditches. In one video, a man is seen begging for his life in a dense forest before being shot point-blank, followed by another shot to ensure he is dead. His body was then dragged and dumped in a ditch with other decomposing corpses. In another video, set in an unidentified forest area, a woman is stripped naked and forced to lie beside the dead bodies of other victims before being beheaded and mutilated. They were near a ditch where bodies were dumped.

Although the forests in southern Nigeria are not as vast as those in the north, they are still large enough to enable these groups to evade security forces and establish dumping grounds for victims. The military has found remains in shallow graves and compounds and sometimes intercepts members trafficking skulls and other body parts, presumably for rituals.

If the rants of a local anti-Biafra influencer, Ijele Speaks II (@IjeleSpeaks2), are true, there are many more gravesites to be found in uncharted parts of Arondizuogu and Arochukwu, Imo state, as he claimed on an X/Twitter broadcast in November last year. However, the 2024 raid of Arochukwu did not uncover any gravesites.

How fighters are stationed

In a video clip, four young men who looked badly beaten were tied up and placed beside each other on the floor by fighters of IPOB’s Eastern Security Network (ESN). These boys were also IPOB fighters—foot soldiers who had left their post and were now paying the price. The man with the camera advanced to the first man and asked him to introduce himself, to which he responded that he was an ESN fighter. The same question was posed to the others on the ground, and they replied similarly. They also talked about their posting in the bushes and their duty to serve as guards to protect the forest base, presumably including abductees.

Why did they leave their post? They were homesick. They snuck away for a while to touch base with familiar grounds in the community, meet with friends and ‘buy’ a goat. This is typical of how the group posts fighters. First, they recruit locals from rural communities, then they station them near those communities.

In another video, a man was bundled up in the back of a police pickup truck, bloodied and emotionally broken from his encounter with security personnel. He was a family man whose wife had just given birth. He seemed like a decent husband, even taking time off from the insurgency to be with his wife and newborn. But for some reason, he was back out with the group that day when he was arrested. However, he was cooperative and vowed to lead the state forces to the hideout of his commanders. He did not know the name of the place, but it was not in the bush and he could easily trace the compound in the community.

Not all of the camps are situated within the forest. Sometimes, they are inside various households of IPOB commanders. These are often used as bomb-making and weapon-assembling grounds and sometimes as attack launchpads. The military has encountered several of these residential bases. The coordinates of a March 2022 raid led to a residential area close to Orsumoghu Forest. The raid was conducted about a month after members of the group ambushed a team of soldiers on the road leading to the village. The security personnel recovered items similar to those usually found in the bushes.

Sometimes, these raids are in reaction to direct ambushes on security personnel. In a community called Awo-Idemili in Imo state, such ambushes occurred in close succession in early 2022, prompting soldiers to track down the aggressors. Earlier in April, buildings and cars were set ablaze at a local government headquarters in Orsu Awo-Idemili. Midway through the month, they returned to attack state forces nearby. The army launched another raid, tracking the militants to their base.

Tension in Awo-Idemili continued to rise in 2022. The army reported that IPOB militants accidentally stepped on IEDs they had set up for the military. Two months later, the army reported a similar IED attack in the area. This compelled the troops to begin conducting raids to find these explosives in various camps.

“Eke Ututu market has recently become a flashpoint as dissidents often ambush troops using explosives and firearms from within and around the market while troops are on routine patrol,” Brigadier General Onyema Nwachukwu, the army’s Director of Public Relations, reported.

Counterinsurgency in the region

By 2016, the Nigerian military was stretched thin, conducting about 10 different operations across the country. By 2020, this expanded to more than 40 operations as insecurity grew in the southern region. Over the years, more operations have been initiated and renewed in the South East, from Operation Golden Dawn 1 through 3 to Operation UDO KA, alongside various joint operations with local security forces.

Timeline analysis of mission reports suggests the counterinsurgency efforts became intensified towards the later months of 2021 under Operation Golden Dawn 1. This coincided with the growth of the group. A policeman in Imo state explained the struggle of fighting the group:

“The problem we are having is that these boys or these men, what they normally do, they do kidnapping, attack police stations, burning down police stations and government facilities, once they are through with that, they go back to their hideouts in the bush.”

He added that the challenge is not just tracking the hideouts of these groups but actually those who recruit and fund them from outside the country. According to him, actors in the diaspora can always recycle fighters from the rural poor with payment, arms, and promises of reward for fighting for freedom.

“Someone that is educated and has a means of living will not be involved with something like that,” he told HumAngle, drawing attention to the backdrop of poverty in the region and its influence in recruiting a seemingly limitless pool of fighters.

HumAngle recently highlighted how the diaspora supporters call for direct attacks on the government and people through coordinated disinformation and propaganda campaigns. A key figure, Simon Ekpa, leader of IPOB’s violent wing, who is based in Finland, has on numerous occasions called for attacks on security personnel at checkpoints and their bases.

Following these calls for violence and increased security threats, there has been a higher concentration of checkpoints across the region. Travellers plying the highways often decry the tedium of passing through these checkpoints, with most being forced to dismount their vehicles and walk the distance of the checkpoint. This protects against ambushes while facilitating security assessments.

The crisis in the South East is a complicated issue. With various factions of non-state actors operating in the area, it is hard for security forces to keep track, especially when they can easily blend with the local communities with which they are familiar.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.