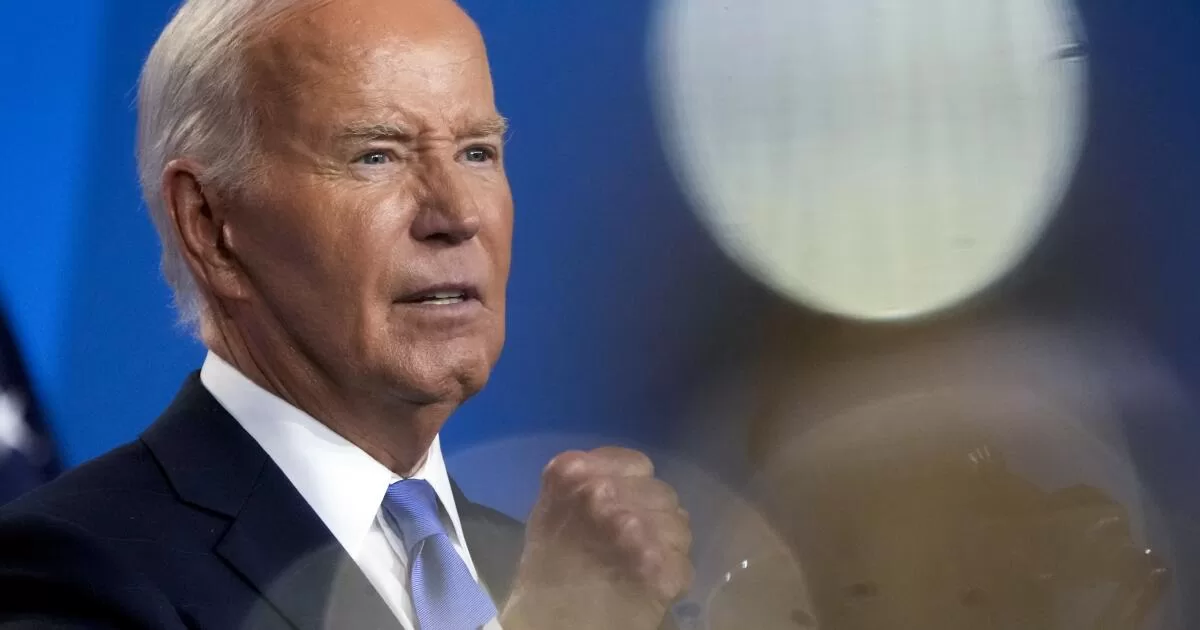

The news from Milwaukee and the Republican National Convention has dominated this week, but it hasn’t stopped speculation about whether Joe Biden will or should withdraw as the Democratic presidential nominee. A lot of Democrats who want a change are eager to have an open contest, to let the wild rumpus begin at the Democratic convention in Chicago in August.

The hope that the way to victory is an open convention is a pipe dream.

For many members of Congress and others sophisticated about politics, a wide-open nominating convention in Chicago in four weeks is the best way to come up with a dream ticket — Whitmer-Warnock seems to be the one mentioned most. At minimum, they want to have a contest, an open process that yields the nominee. To some, if Kamala Harris prevails in that setting, directly vanquishing other rivals, it would bolster her candidacy. And the excitement of a wide-open convention would give the Democratic ticket the jump start it needs.

A little history is in order. The last time there was a convention with more than one ballot was in 1952. Both parties held some primaries that year, but they were basically beauty contests that did not choose nominees. The Democratic nominee, Adlai Stevenson, didn’t even run in a primary; at the convention (in Chicago, by the way), he was drafted and won on the third ballot. Republican candidate Dwight Eisenhower split primary victories with his prime rival, Robert Taft, but those outcomes had little to do with his final nomination.

Although every convention since has seen the nomination resolved on the first ballot, there have been plenty we can call open — contested conventions, where candidates jostled and the disgruntled were determined to make their unhappiness known.

For Republicans, consider the 1964 convention at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. Barry Goldwater was a first-ballot victor, after his rival, the newly divorced and remarried Nelson Rockefeller, flamed out, but not before Republican moderates led a last-ditch effort behind Pennsylvania Gov. Bill Scranton to wrest the nomination away. Bitterness on the convention floor, including Rockefeller being nearly hooted off the podium, left a fractured party. Goldwater would likely have lost in any case, but his defeat by Lyndon Johnson was wider and deeper as a result of the fractures demonstrated at the convention.

Then there was 1976. At Kemper Arena in Kansas City, Mo., the Republican nomination was in serious question as the convention began. Incumbent Gerald Ford, who did not have a majority of delegates, faced a fierce challenge from Ronald Reagan. Ford eked out a victory on the first ballot, but a large number of unhappy conservatives threatened to bolt the GOP and form a new party, which contributed to Ford’s narrow defeat at the hands of Jimmy Carter.

For Democrats, of course, Chicago in August could be déjà vu all over again. Their 1968 gathering is the limiting case of a contested and bitter convention, one where the withdrawal of the incumbent Johnson, spurred by a challenge from Minnesota Sen. Eugene McCarthy, led to a struggle between Robert F. Kennedy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey that was upended by Kennedy’s assassination that June. Most of Kennedy’s delegates went to Humphrey, who won the nomination handily on the first ballot. But anti-Vietnam War demonstrations outside the convention hall were met with tear gas and violence from Chicago police, and after Connecticut Sen. Abe Ribicoff used the podium to decry Mayor Richard J. Daley’s “Gestapo tactics,” the vivid image inside the hall was Daley shaking his fist and shouting an antisemitic epithet at Ribicoff. All of it left Humphrey with the opposite of a “convention bump.” He fell just short in November, a defeat easily attributable to mayhem at the convention.

The Democrats had at it again in 1980 in New York City. The incumbent Carter easily prevailed at winning renomination, but only after a hard-fought challenge from Massachusetts Sen. Edward M. Kennedy. Kennedy’s defiant convention speech was anything but a full-throated endorsement of the nominee. He closed by saying, “For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.” The divisions exposed at the convention were not the only cause for Carter’s loss to Reagan — the U.S. hostages seized in Iran and “stagflation” were key. But the disunity didn’t help.

The main reason even these contentious conventions required just one ballot, and most others are showcases of party unity, is that, for all its flaws, the primary-driven nominating process works. In state-by-state contests, candidates who fail — who can’t win or place in key races, who find money drying up — cannot easily claim to have been robbed. The nominee emerges fair and square, and the process provides time and opportunity to heal the wounds among party factions.

There is no question that Democrats are deeply divided over whether Joe Biden is the best choice for the party in an existential election against a Republican nominee who pledges a presidency of retribution and a dictatorship on Day 1. But in the event Biden withdraws, the party needs an alternative to a barnstorming free-for-all in Chicago.

The obvious path is simply to pass the torch to Vice President Harris, and make the convention one where Democrats can both have the excitement of choosing a new running mate and yet directly make the case for the Biden-Harris record and for democracy, reproductive rights and political integrity. The only other option would be a more controlled mini-contest, three weeks or so of debates with perhaps three or four candidates, followed by ranked-choice voting at the convention. But that course has its own pitfalls — who would choose which candidates and put into place a mechanism for an expedited ranked-choice vote on the convention floor?

There is no sugarcoating the mess Democrats find themselves in right now. But they need to keep it from getting even messier, and soon.

Norman J. Ornstein is an emeritus scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and co-host, with Kavita Patel, of the podcast “Words Matter.”