Bangladesh has been rocked by student protests for nearly three weeks.

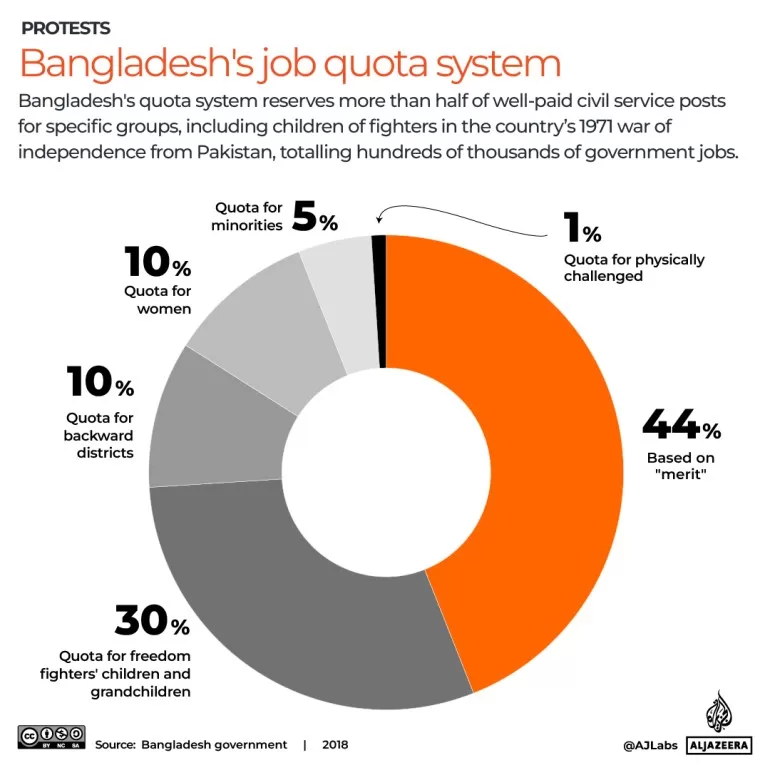

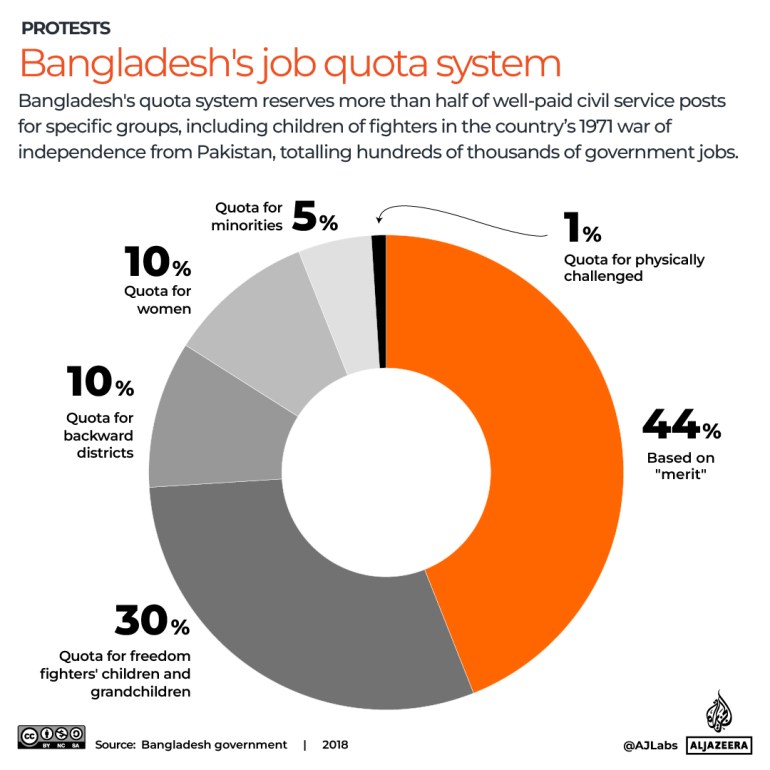

Since July 1, university students have been protesting across the country to demand the removal of quotas in government jobs after the High Court reinstated a rule that reserves nearly one-third of posts for the descendants of those who participated in the country’s 1971 liberation movement.

Following the High Court’s ruling in June, 56 percent of government jobs are now reserved for specific groups, including children and grandchildren of freedom fighters, women, and people from “backward districts”.

Student protesters have clashed with police and members of Bangladesh Chhatra League, a student wing of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s governing Awami League party.

Six people have been killed and hundreds of others injured.

Who are leading the protests?

The demonstrations are notable not only for their size and intensity, but also their demographics.

“Look at who is protesting,” Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center, told Al Jazeera.

“It’s not just a case of grassroots demonstrations led by the poor. These are university students most of whom are above working class … The fact that you have so many students who are so angry speaks to the desperation of finding jobs. They may not be desperately poor, but they still need to find good, stable jobs.”

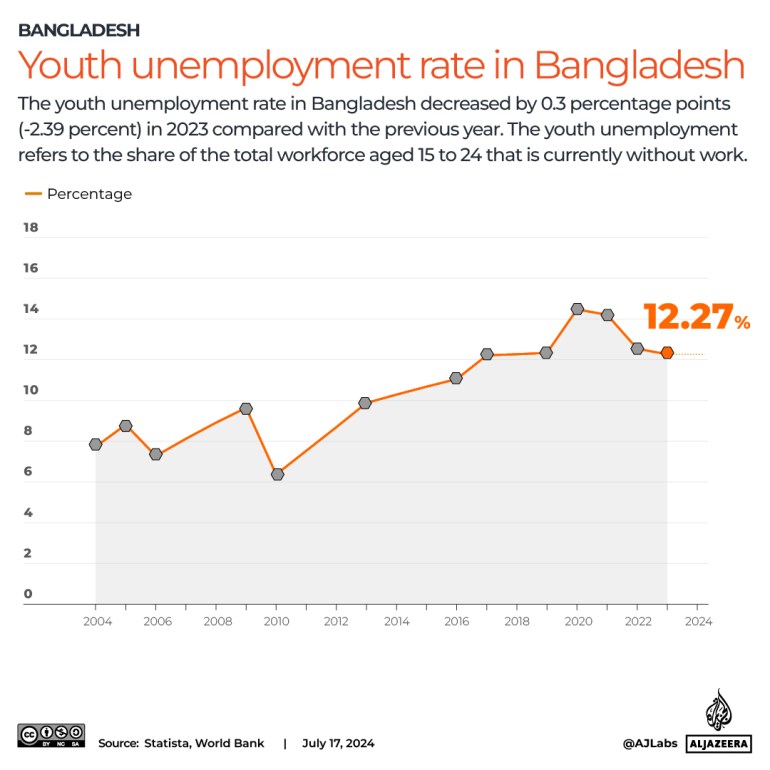

About 67 percent of Bangladesh’s 68.6 million people are in the legal working age group of 15-64 and more than a quarter are between the ages of 15 and 29, according to the International Labour Organization.

“So you’re looking at a situation where there’s a significant working-age population,” Kugelman said.

Vina Nadjibulla, vice president of research and strategy at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, said the South Asian country faces an “acute job crisis for university graduates”.

“The 30 percent quota will hit that group,” Nadjibulla told Al Jazeera.

The protests stand out all the more because of the significant economic gains that Bangladesh has made in recent years.

The economy has grown at an average of 6.25 percent annually over the last two decades.

Poverty declined from 11.8 percent in 2010 to 5 percent in 2022 based on the international poverty line of $2.15 a day.

In the process, it also surpassed its much bigger neighbour India in terms of per capita gross domestic product (GDP).

Bangladesh has also seen a marked improvement in its human development outcomes and, as a result, is on track to graduate in 2026 from the United Nations List of Least Developed Nations.

Where is Bangladesh’s economy falling short?

Despite those successes, “there is still a lot of inequality and poverty”, with at least 37.7 million people reportedly experiencing food shortages last year, Nadjibulla said. “The growth is not trickling down to the educated university students who are taking to the streets,” she said.

Kugelman said the country risks missing out on the opportunity to capitalise on its demographic dividend.

“That’s the big issue. The stakes are particularly high,” he told Al Jazeera.

Bangladesh’s economic rise stems largely from readymade garments (RMG) exports – predominantly to the West – and remittances from workers abroad.

“It is struggling to find a comparable” sector to RMG, said Kugelman.

“It needs ways to attract more FDI [foreign direct investments] to spark and sustain newer sectors. If you create more sectors and more diverse exports, jobs will follow.”

Nadjibulla said the government needs to ensure there is appropriate education and training to match the needs of the workforce.

Last year, about 40 percent of Bangladeshis aged 15-24 were not working, studying or training.

Nadjibulla said the efforts of global businesses to expand their supply chains beyond China could be an opportunity for Bangladesh.

“That is where education reforms become critical,” she said.

“What we are seeing right now is a complex interplay of government shortcomings, inequality and youth disenfranchisement and disenchantment with the government of Sheikh Hasina.”