Out of wartime necessity, Ukrainians tend to be keen observers of U.S. politics. And for the Ukrainian government — as well as its European backers — the tumult of this American campaign season is viewed with growing alarm.

Those worries were crystallized this week by the selection of J.D. Vance, a vociferous critic of U.S. aid to Ukraine, as running mate to former President Trump.

Over the last 21/2 years, as Ukraine has struggled to fend off a Russian onslaught, billions of dollars worth of military assistance from the United States and its European allies have been a critical lifeline. Now, the outlook for long-term support appears more clouded than at any point in the war.

“There was already considerable concern about the durability of the future U.S. commitment to Ukraine, and more broadly about the commitment to NATO,” said Ian Lesser, a distinguished fellow with the German Marshall Fund in Brussels.

The choice of Vance for the No. 2 spot on the GOP ticket, he said, “is only going to reinforce those concerns.”

Publicly, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has telegraphed confidence his government can weather whatever storm might be approaching.

On Monday, he told reporters in Kyiv that “we will work together” with any U.S. leadership.

Some in Zelensky’s circle are already pointing out that a vice president’s foreign policy views traditionally do not carry great weight in U.S. administrations, and that in the event Trump were elected, his voice would be the only one that would count.

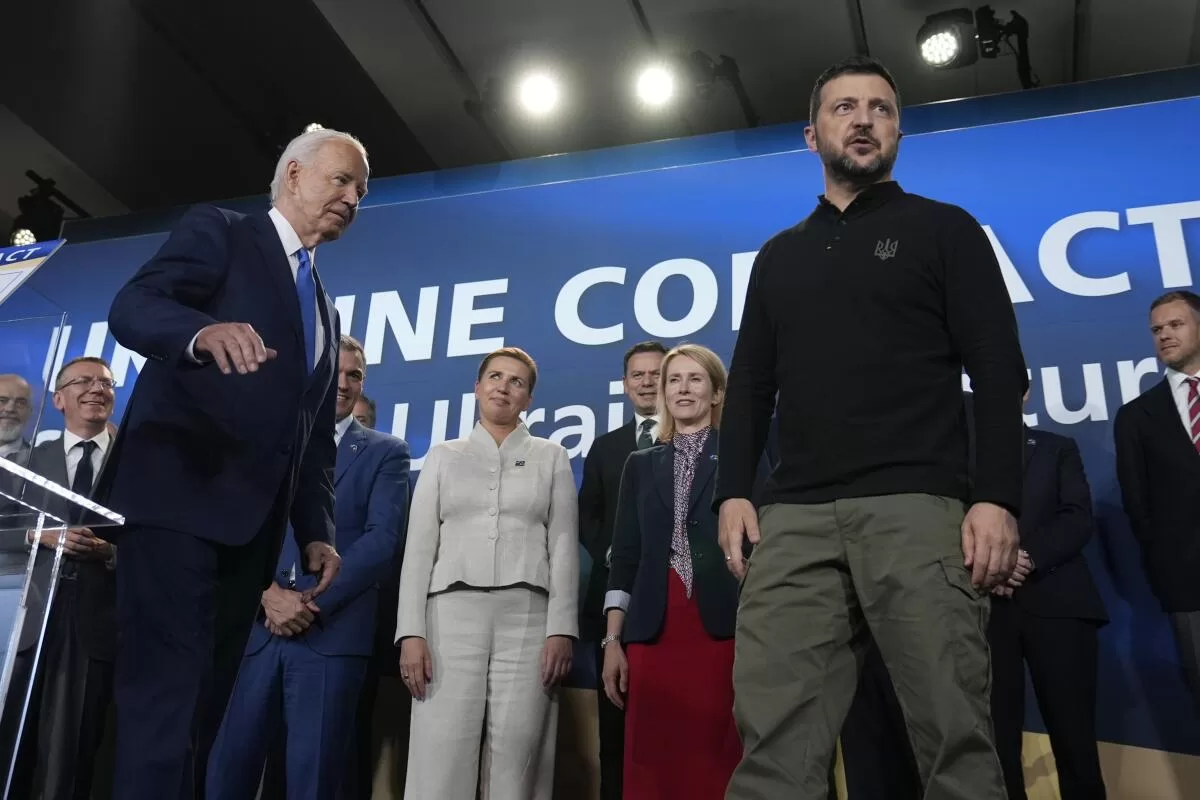

President Biden with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky during the NATO gathering in Washington last week.

(Susan Walsh / Associated Press)

But many close observers of the war in Ukraine believe a Vance vice presidency, if it came to pass, would serve to amplify what analyst Jessica Berlin called Trump’s “worst impulses” — including a notable willingness to take a benign view of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Vance is “an outspoken proponent of pro-Russian, pro-Putin policies,” said Berlin, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. “And he’s particularly dangerous because he is a sharper communicator than Trump.”

Like Trump, his running mate has called for a quick end to the war — which Zelensky’s camp considers code for a demand that it cede territory to Russia, consigning Ukrainian citizens in occupied cities, towns and villages to a brutal fate.

In February, Vance startled some attendees at the Munich Security Conference, a showcase gathering for the Western foreign policy establishment, by minimizing the Russian threat to Europe, and showing no interest in engaging with those who wanted to talk about why a Russian victory would be so dangerous.

Although it garnered little attention at the time, one particularly stark comment from Vance — who was then in the midst of what would turn out to be a successful campaign to represent Ohio in the U.S. Senate — still makes Ukraine backers bristle.

“I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or the other,” he said in a 2022 podcast interview with Trump ally Stephen K. Bannon that aired just two days before Russia’s full-scale invasion began.

For supporters of Ukraine, Vance’s selection is also a reminder of his prominent role in a congressional battle that resulted in a six-month holdup of a $61-billion U.S. aid package, a logjam that broke in April when House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) allowed a vote to release the assistance.

At the time, Ukraine hoped the long delay, whose ramifications are still being felt on the battlefield, was an aberration that did not reflect a lack of U.S. public support for the Ukrainian cause.

Even before Vance’s addition to the Republican ticket, the internal Democratic struggle over whether age and infirmity should preclude President Biden from serving another term had been causing jitters in Europe, although allied leaders have carefully refrained from any public expression of concern over Biden’s fitness to run.

But the triumphal spectacle of this week’s Republican convention — which came on the heels of an assassination attempt against Trump at a Pennsylvania rally — coincided with quiet efforts on the part of some key European leaders to avoid being caught off guard if events seemed to be tilting in Trump’s favor.

In Germany, for example, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left party dispatched a delegation to the Republican convention in Milwaukee to assess the mood.

“We want to be better prepared for a possible Trump victory than we were eight years ago,” the party’s foreign policy spokesman, Nils Schmid, told Germany’s RND network.

Sitting European leaders, with a few exceptions, are generally circumspect about internal U.S. politics, but former ones offered up some acid commentary about Vance’s selection.

“More champagne popping in the Kremlin,” Guy Verhofstadt, a former Belgian prime minister, wrote Tuesday on X about the new vice presidential candidate.

Some in Ukraine expressed hopes that Vance, a former U.S. Marine, might yet change his stance on the conflict if they were able to show him personally what was at stake. After all, they reasoned, the onetime “Never Trumper” changed his mind about Trump.

“We need to try and convince him,” Yevhen Mahda, executive director of the Institute of World Policy think tank in Kyiv, told the BBC. “He fought in Iraq, therefore he should be invited to Ukraine so he can see with his own eyes what is happening, and how American money is spent.”

Among the European far right, though, the selection of Vance rekindled hopes that if Trump were elected, figures such as Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who has tried to quash European backing for Kyiv, would have a powerful new ally in Washington.

“A Trump-Vance administration sounds just right,” Orban political aide Balazs Orban, who is not related to the prime minister, wrote on X. “Vance is definitely the best choice.”