Trapped in a time-worn narrative, the United States is a nation haunted by the echoes of its 20th-century historical preeminence. Nowhere in Washington can you escape the ghosts of America’s much-idealized past and swagger. Its once formidable economic successes — envied, admired, and emulated the world over — precipitated by a fervent belief in its ideological and military superiority and cultural cache remain the talk of the town despite evidence of the nation’s growing social malaise, economic decline, and its foreign policy misadventures in Iraq and Afghanistan. Yet, in the second decade of the 21st century, America’s political establishment remains equally enraptured and entrapped by historical narratives that once propelled the nation to the pinnacle of global dominance.

An astute observer of Washington’s political scene and its myriad vaunting incarnations will note, however, that the once unassailable colossus of the 20th century remains very much a hostage to outdated paradigms of a bygone era that continue to shape America’s domestic and foreign policy, often it might be added, to the detriment of its international standing and prestige. As U.S. demographics shift and the rest of the world has advanced, modernized, and adapted to new post-Cold War realities, the political establishment in Washington clings to a nostalgia that is conspicuously anachronistic. Heeding Jefferson’s dictum that the present cannot be governed by the dead hand of the past, the United States has a distinct opportunity to reimagine the world to meet the geopolitical challenges of the day.

Beyond the Iron Curtain

During the Cold War, the United States perceived the world through a binary lens of great power competition with the Soviet Union and its constellation of satellite states as its principal adversaries. An intense rivalry between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, fueled by a clash of competing ideologies and superpowers, condemned millions to life of relative material destitution and mental indoctrination behind the Iron Curtain. Despite the Cold War having receded with the fall of the Berlin Wall over three decades ago and the burgeoning multilateral institutional architecture established on the belief in liberal internationalism took its place, the U.S. political establishment nevertheless persists in framing international relations as an invariable zero-sum game defined by adversarial competition. The increasing clout of China and a resurgent Russia provide ample opportunities for the assertion of realism. Both countries take full advantage of refining their interests in terms of power. Yet, this perspective alone egregiously fails to acknowledge the multifaceted, multipolar reality of today’s global order and the economic, social, and political developments that have taken root in modern and increasingly dynamic populations of the so-called Eastern bloc and much of the Global South.

Despite witnessing thirty years of remarkable economic development and generational shifts in ideological realignment towards, paradoxically, market economic models and in some instances liberalism, the United States behaves as if the Soviet man has not perished with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, as if the remnants of the Berlin Wall still lay dormant in Eastern Europe’s backward alleys and sidewalks, and as if China was the natural successor to the West’s feverish ideological and military confrontation, taking the place of its much-maligned Cold War predecessor. The United States and its Western allies created multilateral institutions with an explicit goal of facilitating dialogue and engagement yet today collectively pursue militarism as a form of persuasion, arguing dubiously that military deterrence will singlehandedly dissuade near-peer competitors from advocating for their sovereign national interests based on their own discrete security and threat assessments.

The Cold War Heuristics and Narrative Fallacies

The United States continues to interpret global events through the distorting prism of Cold War-era dichotomies and its many unfortunate “—isms”. Terms such as fascism, Nazism, Stalinism, totalitarianism, and authoritarianism are frequently invoked to characterize adversaries, even when these labels alone fail to capture the intricate realities of contemporary geopolitical dynamics. The reliance on outdated heuristics distorts American perceptions of current events and precipitates policies that are often misaligned with the complexities of the modern world. As Christopher Fettweis put it in Psychology of a Superpower (2018), “the ubiquitous Hitler analogies are rhetorical, to support policy decisions already made ”(119) and supported in myriad different ways in newspaper articles and media reports. Analogizing history through the lens of the enemy image, Fetweiss contends, demonstrates “intellectual and moral sloppiness”, “implacable hostility”, “muddled thinking”, and “shallow (or dishonest) thinking” (120) leading the public to believe in some “secret, nefarious, long-term master plan” (120) of devious rogue actors bent on expansion and influence.

Recent headlines from influential English-language publications demonstrate this point well. Take Le Monde’s headline for its opinion editorial on June 19, 2024, as a projection of the West’s greatest fears unto the rapidly shifting geopolitical landscape — “Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un’s worrying summit of pariahs” or The Economist’s “Vladimir Putin’s dangerous bromance with Kim Jong-un” or Washington Post’s “Xi Jinping’s authoritarian rise in China has been powered by sexism”.

The superficial portrayal of Russia in terms of its Putinism or of China in terms of Xi’s monolithic one-dimensional authoritarianism overlooks the subtleties of their political and economic systems. China’s state capitalism and its integration into the global economy — with the Clinton administration’s assistance and backing — present both challenges and opportunities that cannot be adequately captured and comprehended by Cold War-era thinking. Framing Russia’s actions as a revival of Soviet-style expansionism that will not stop at Ukraine’s borders ignores the distinct security concerns, motivations, and strategic objectives of the contemporary Russian state, which Putin made clear in his 2007 Munich Security Conference address. The Western public is led to believe, however, that Putin’s animus dominandi is so rapacious that his neo-russification agenda will find his army marching into former Warsaw Pact states and thus threaten the security and order of all of Europe.

In his August 2023 Le Monde Diplomatique article, John Mearsheimer dismissed this version of events, no matter how often invoked, as a “myth”. “There is no evidence that Putin wants to incorporate all of Ukraine into Russia”, Mearsheimer argued, “or seeks to conquer any other country in eastern Europe. Furthermore, Russia does not have the military capability to achieve that ambitious goal, much less become a European hegemon.” The supposed viability of Neo-Sovietization of former Baltic states and Poland is itself a “narrative fallacy” or a psychologically satisfying story based on a principle of post hoc, ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this) popularized by Nassim Taleb in his 2007 book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. In it, Taleb uses the term to describe our tendency to create stories or explanations to make sense of the world, even when those stories might misconstrue reality. This cognitive bias leads the public to believe that they not only understand but can predict complex events, when in fact, events are often shaped by randomness and uncertainty.

There is no doubt, however, that by advancing glib rhetoric to publicly denigrate and humiliate rising powers whilst at the same time overestimating their existential danger and hostility can prove costly and counterproductive resulting in the (un)intended consequences which may not necessarily deliver the much-avowed global peace and stability. This is not to argue, as some have rightly done so, that “erring on the sign of caution” is a paramount demand of prudence and that it is better to share in the “paranoia of Churchill” than the “faith of Chamberlain” (Fetweiss,120). But perhaps it is time to abandon old and tried ideological precedents, keeping in mind that history does not have predictive powers.

Shifting Horizons: The New Global Landscape

The rest of the world has largely transcended the ideological battles that once defined the 20th century. Nations across Asia, Europe, and Latin America have concentrated on raising their standards of living through economic development, technological innovation, and regional cooperation. New generations have embraced globalization, liberalization, and institutional reform.

In Southeast Asia, countries have prioritized economic growth and regional stability over ideological conflicts. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports that ASEAN’s combined GDP grew from $1.8 trillion in 2000 to $3.2 trillion in 2021. Many Eastern European countries after joining the European Union, had seen a significant spur in economic growth, benefitting from increased trade and investment. According to the World Bank, Poland’s GDP grew from approximately $65 billion in 1990 to over $811 billion in 2023. Hungary mastered impressive GDP growth of $140 billion in the same period, and the Czech Republic’s GDP grew from approximately $29.8 billion in 1991 to over $330 billion in 2023. Combined with high educational attainment, increased life expectancy, and a decline in general poverty, the figures demonstrate the region’s remarkable transformation from post-communist economies to dynamic, market-oriented democracies.

A recent Foreign Policy article fittingly titled “China’s Public Wants to Make a Living, Not War” expects Chinese military action against Taiwan to meet with fierce public opposition thwarting the regime’s propagandistic overtures at reunification. The 2023 Pew Research Center Poll conducted across 16 countries suggests that “domestic politics and people’s understanding of their own country’s history … heavily inform their thoughts about how their country should behave on the global stage”, yet a significant portion of the young adult population would prefer to “get their own house in order first’ and perceive their country’s overseas involvement as ‘making things worse”. Young adults see climate change as an overarching international priority, followed by “energy independence (for those on the right) or diversification (for those on the left)” and find “value of working with allies and international organizations to solve various world problems via their country’s relative power and diplomatic strength.”

Yet amid shifting global public policy priorities and a yearning for the economic development of the once severely ideological Asian and Eastern European bloc, the United States appears intent on revisiting and perpetuating historical grievances. Yet, promulgating the narrative that any contender to American hegemony is analogous to past totalitarian regimes hinders constructive maturing of the region’s institutions and productive international dialogue. It also perpetuates a sense of American exceptionalism that is increasingly out of step with global realities. Prophesies and oracles about the West’s increasingly belligerent enemies will continue to further antagonize China, Russia, and its allies, bringing the world to an ever-closer nuclear confrontation.

Militarism and the Preservation of History

The U.S. government’s official communique and the auxiliary military-industrial complex play a pivotal role in perpetuating these narratives. The “enemy image” rhetoric calls for increasing government-to-government engagement in building partnerships with like-minded allies. But militarism of U.S. foreign policy, too, serves to keep historical fears and hostilities very much alive and even threatens to expand them to new theaters of potential armed confrontation — to Taiwan, the Antarctic, and outer space.

Former Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman encapsulated the bifurcation of the international system into the democratic “us” versus the authoritarian “them” in February 2023 by calling for a new strategic vision of what the new world order demands in a world of aspirational autocracies. She emphasizes the evolving threat posed by Xi Jinping’s leadership in China, highlighting his ambition to reshape the global rules-based order, underscoring the importance of defending democratic values while urging domestic investment and bipartisan cooperation to strengthen national resilience. For the Biden administration, aligning with allies and partners to effectively counter challenges posed by China and Russia is a fundamental test of democratic values both at home and abroad. Time will tell if the 2024 presidential election cycle significantly upsets this narrative.

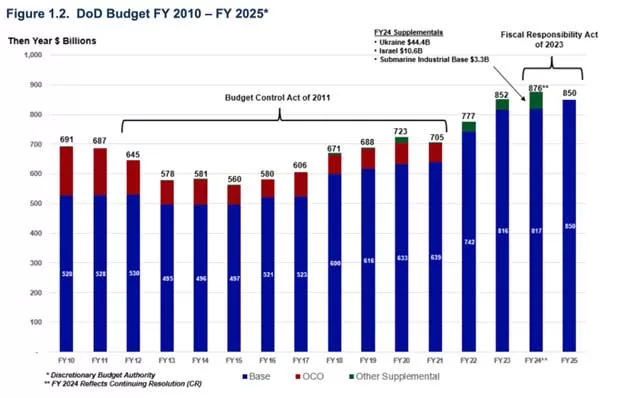

In the meantime, military expenditure continues to rise, with the U.S. allocating approximately $721.5 billion to defense in 2020 and $816.7 billion in 2024, respectively. The proposed Department of Defense (DoD) budget for Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 of $849.8 billion is awaiting its final stamp of approval.

source: Defense Budget Overview

The emphasis on military solutions over diplomatic engagement reinforces the perception that the U.S. is preparing for conflicts reminiscent of the 20th century’s inglorious past rather than addressing contemporary challenges through multilateral institutions and cooperation.

A Path Forward

Literature on the psychology of superpowers suggests that the United States suffers from a chronic misperception of enemies. As intimated earlier, the three key indicators of foreign policy distortions, include (1) The argument that the enemy regime is simulations dangerous and fragile. Thus, newspaper reports state that Russia is a formidable threat to Europe yet its military is weak and its power on the world stage is largely inconsequential. (2) Their word cannot be trusted because (3) They are Nazis with Hitler incarnate as leader. In the words of George Kennan “people need to think that there is, somewhere, an enemy boundlessly evil, because this makes them feel boundlessly good.”

In order not to fall victim to misperceptions of hostility and invariably push the new ‘axis’ powers into each other’s mutual sphere of interests and influence, the United States must:

1. Reframe Its Worldview: The U.S. must update its perception of global affairs, recognizing the multipolar nature of the current world order. This would involve moving beyond the great power competition paradigm and acknowledging the satisfaction derived from the economic and political advancements of other nations. Providing strategic vision, incentivizing cooperation, and avoiding predictable punishments in the form of sanctions, tariffs, or shallow diplomatic commitments and threatening rhetoric.

2. Incorporate analysis and policy prescriptions: Washington should move beyond these solipsistic Washington DC policy circles and incorporate the perspectives of a broader array of voices, both domestically and internationally. This includes engaging with dissenting opinions and considering the economic and security interests of other countries, especially those that have experienced rapid modernization. It should also be mindful of specific security concerns of its near-peer competitors and align its diplomatic priorities accordingly.

3. Abandon Fear-Mongering: The rhetoric of “us versus them” is counterproductive. The U.S. should adopt a more nuanced approach, focusing on building partnerships through humility and mutual respect. This means moving away from ultimatums and threats of sabotage. Additionally, the portrayal of adversaries as the next Mao, Hitler, or Stalin is an ill-advised fear-mongering tactic that stifles nuanced analysis and diplomatic solutions. This approach alienates potential allies and fuels global resentment towards American policies, particularly in the non-aligned Global South. For the United States to remain a material and ideological force for good in the 21st century, it must desist from manufacturing fears, reframe its perception of the present, and desist from abusing history to its advantage. Whilst fear gives a valuable point of reference, it can also severely distort reality and serve as a malign manipulation tactic to which the far more circumspect and better-informed global public has become increasingly immune.

4. Emphasize Diplomacy and Multilateral Engagement Over Militarism: A shift in focus from military intervention to diplomatic engagement is essential. An apt 2016 book title of How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything by Rosa Brooks captures the collapsing barriers between war and peace well. The U.S. should prioritize international cooperation, multilateral conflict resolution, and economic development as primary tools of foreign policy. Elevating militarism as a foreign policy instrument begets militarism at home and abroad and frays the very fabric of America’s constitutional order.

By moving away from the strategy of “might is right” and offering an inspiring vision for the 21st century based on an accurate understanding of the global community’s policy preferences and human aspirations, the United States can extricate itself from the now-ossified ideological battles it once waged and won. As the unipolar moment gives way to multipolarity, the United States must modernize domestically, update its crumbling infrastructure, invest in its strategic industrial base, and cultivate a forward-thinking, open mind and agile attitude towards friends and enemies alike. After all, as Alexis de Tocqueville noted “America is great because she is good, and if America ever ceases to be good, she will cease to be great.”