Oz Perkins is no stranger to the public eye. His parents — fashion model Berry Berenson and “Psycho” star Anthony Perkins — were both celebrities. He’s no stranger to darkness either: His father was forced to live a life in the closet, and his mother died in one of the planes hijacked during the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It’s a lot for one person’s family history.

Maybe because of this, horror movies have always been a part of Oz Perkins’ life. His fourth film, “Longlegs,” is his scariest. It follows FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) as she tracks down an Oregon serial killer (Nicolas Cage). It’s poised to be a major breakthrough for the director, thanks in part to a herculean marketing campaign from distributor Neon. It’s also completely terrifying, crafting an atmosphere of unrelenting dread.

One of Perkins’ most formative experiences was watching Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining.” He remembers the first time he saw it. “We used to take our summer vacations in Cape Cod, Mass., and we watched it in a house with these glass walls, and you could sort of see out into the woods,” the director, 50, recalls via a Zoom call from his Los Angeles home. “I remember trying to sleep with that backdrop. It was a rough night.”

When it comes to writing screenplays, Perkins always draws from his own experiences. “I made a decision early on that characters are going to essentially stand in for me in some way or another,” he says. The description of the glass-walled home where he watched “The Shining” is not unlike the one Monroe’s Harker inhabits in “Longlegs,” and her ability to see only a certain distance into the woods is a key aspect of a sequence.

A scene from the movie “Longlegs.”

(Neon)

His second feature, 2016’s eerie, slow-burning ghost story “I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House,” was dedicated to his father and even includes a clip of Perkins’ Oscar-nominated performance in William Wyler’s “Friendly Persuasion.”

“It was about how we want to know who our parents are, and sometimes we don’t get that desire until they’re gone,” he says. “It can be impossible to learn who someone is when they’re not around anymore.”

“Longlegs,” written and directed by Perkins, is about how “our parents can construct a story. It can be an old story that’s part of the family lore for generations, but it can also be a generational karma that’s passed down, something you have to continue to deal with and explain. A secret or challenge that can be withheld.”

That imposed secrecy, especially as related to his father, had an unmistakable effect on Perkins that continues to influence his work. “I think when one lives in that environment where there’s the whole, full truth — the concealed truth — and the version you’re fed,” Perkins says, “that creates layers of mystery, intrigue and curiosity. And that’s what I’ve tried to impart on the pictures that I make.”

Perkins has warm memories of his dad. He’s seen all of his films, although they didn’t watch them together. (“If your father’s a dentist, they don’t bring you in to look at people’s mouths,” Perkins remarks, sharply.) Instead of bonding over movies, father and son found kinship in their shared sense of dark humor. “My dad was known in his circles as being super dryly funny and came at things with an abstract and surreal sense of humor,” Perkins remembers. “And I’m proud to be able to express that myself, especially in the movies I make, which at times I really do think are quite funny.”

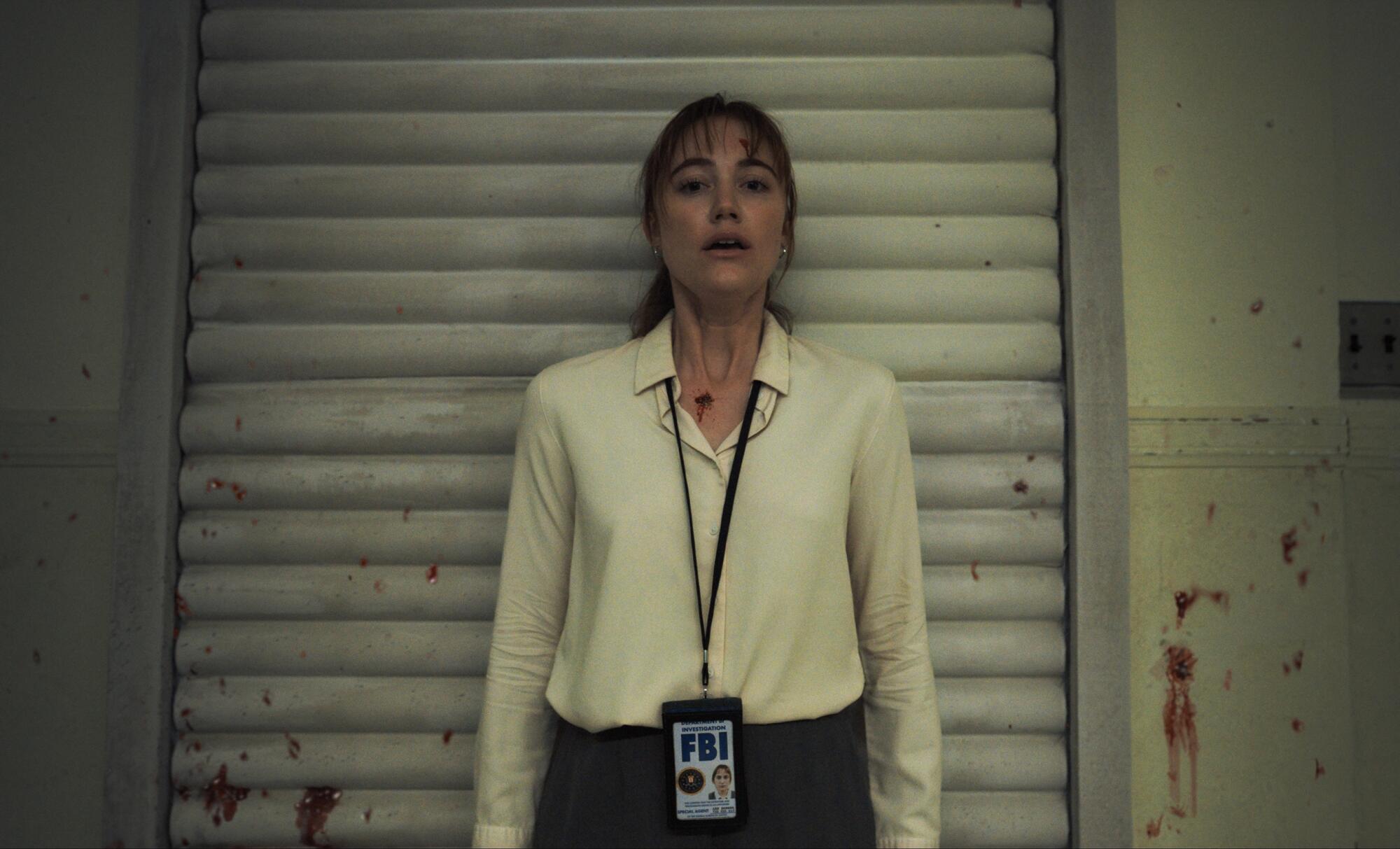

Maika Monroe in the movie “Longlegs.”

(Neon)

Horror thrives on the unexpected. “Longlegs” draws you in with familiarity before plunging you into something more unforgiving. Set in the 1990s and centered on an intuitive but untested female protagonist, its closest comparison is Jonathan Demme’s “The Silence of the Lambs,” a resonance Perkins uses to his advantage.

“The idea was to come in on the wings of ‘Silence of the Lambs’ and use it to do something radically different,” Perkins says. The idea of employing a film as dark as Demme’s crime landmark as a palate cleanser for “Longlegs” shows just how nasty Perkins’ movie is.

Though the thriller builds an impressive mood over time, the scares are there from the start. That’s a deliberate move by Perkins. “You want to make sure the audience is with you as soon as they can be,” he says.

It’s a lesson he learned from the great filmmaker Mike Nichols, who took Perkins under his wing after his father died in 1992 when Oz was 18. Says Perkins, “Mike demonstrated to me that as a director, you have the ability, power and opportunity to plant a point of view into everything you do, and if you want to give your film body, texture and depth, it’s essential.”

He looked beyond the horror genre to establish the movie’s unique visual style, pushing cinematographer Andres Arochi toward the work of director Gus Van Sant. “If you plant the seed of something unexpected,” Perkins says, “it automatically turns artists onto a different channel. ‘My Own Private Idaho’ is going to be a far more important reference than ‘Rosemary’s Baby.’”

Though Perkins’ films are terrifying, actors love working with him. “Oz’s filmmaking style is a relaxed, humble confidence with a twist of ironic humor,” “Longlegs” co-star Blair Underwood writes via email. “His dash of humor is just the icing on the cake to create a creatively safe and daring work environment.”

“He lets his work breathe through others and doesn’t hold on so tight that he strangles it,” adds Monroe.

That sense of freedom is exactly what lured Cage to deliver some truly inspired work as the titular Longlegs — a deeply unnerving performance (even for him). He lives in a dark lair with a T. Rex poster. His hair is long, lanky and gray, makeup a corpse-like white, and prosthetics render his face into something masklike and practically inhuman. Longlegs suddenly bursts into chilling bouts of song. Cage is unrecognizable with a high-pitched raspy voice; you’d be forgiven for having no idea he’s even in this.

It’s the kind of role that requires a complete commitment, and that’s exactly what Cage delivers. “It was clear what a deliberate, careful, considerate and focused actor — and human being — he is,” Perkins recalls thinking from their first meeting.

They found themselves sharing ideas at all hours, with Cage sending Perkins voice notes of potential options for Longlegs late into the night. “It was both of us doing it together at all times,” the filmmaker says. “No part of Nic is in it for himself. He likes to collaborate as much as anybody I’ve ever met.”

While filming “Longlegs,” Cage didn’t want to mingle with cast or crew after each day’s shooting, keeping his focus entirely on his role. This wasn’t in a Method actor way, Perkins assures me, but because that isolation served one of the film’s most harrowing scenes: Longlegs and Harker meeting for the first time. That was also the first time Monroe met Cage. She had no idea what he’d look like, sound like or act like.

“It felt like I was really loading the deck for an opportunity to get some real emotion and presence in a scene,” Perkins says. Because of Cage’s commitment, they were able to capture a moment of genuine shock and spontaneity that’s sure to rattle audiences.

Perkins has already filmed his next movie, “The Monkey,” based on a 1980 Stephen King short story. But bracing for another all-out horror excursion would be a mistake, he insists.

“‘The Monkey’ is nothing like ‘Longlegs’ in any way,” Perkins assures me. He describes it as a comedy “with lots of really extreme cartoon gore” and counts “An American Werewolf in London,” “Gremlins” and “Death Becomes Her” as references.

Perkins also returns to acting in “The Monkey,” something he’s not done since Jordan Peele’s “Nope.” His first performance was as a young Norman Bates in 1983’s “Psycho II.” Typically, he finds the lack of control in acting nerve-racking, which is why he’s largely transitioned to behind the scenes.

For Perkins, though, you get a sense that challenging himself as much as the viewer is part of the fun. “That’s the whole game, isn’t it?” he says. “Give them what they don’t think they want.”