In better times, Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign was full of flash: a launch rally that drew more than 20,000 people to Oakland, a five-day summer tour of Iowa on a luxury bus with her name blazing from the side in colorful capital letters, a robust multi-state operation headquartered in Baltimore.

Now, the bus has been swapped for a nondescript black SUV. The campaign stops are more intimate than immense — a few dozen people in a pastoral red barn, several hundred in a pub. And her efforts have narrowed to a single make-or-break prize: Iowa.

To revive her flagging campaign, Harris is betting big on going small. It is a marked tonal shift and a strategy born of necessity, reflecting her dwindling cash and limp poll numbers.

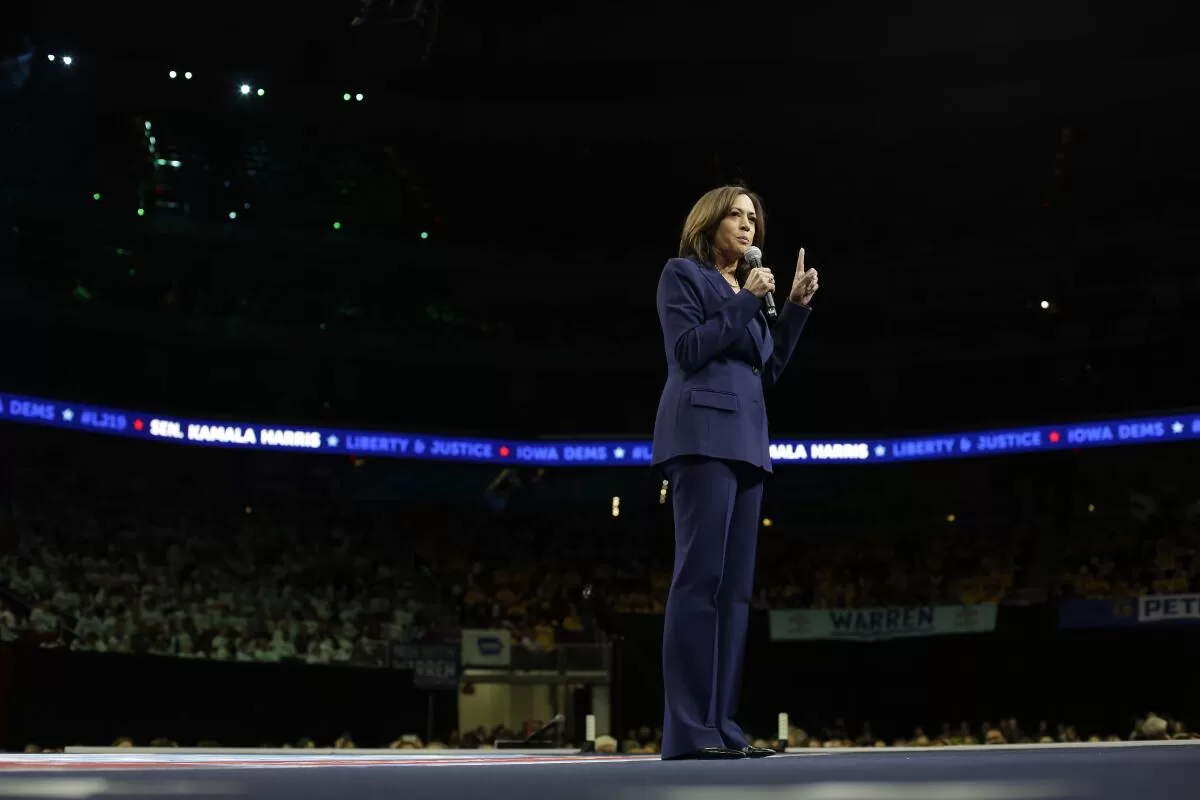

The California senator proved she can still deliver a high-wattage performance, earning glowing reviews for an energetic speech Friday night at a major gathering of Iowa Democrats. But her October blitz in Iowa largely focused on humbler settings — making dinner in supporters’ homes and dropping in on small businesses, in hopes that one-on-one encounters can help close the deal with caucus-goers who will make or break her presidential aspirations.

“The obvious risk is you’re not speaking to large crowds,” said Dan Callahan, a 57-year old contractor from Independence who attended the Harris town hall in a Winthrop barn. But he pronounced the personal approach a “good thing.”

“It’s what Iowa expects,” he said. “It’s what we’re used to.”

Iowa‘s Feb. 3 caucus wasn’t always so central to Harris’ plan. Her strategists’ hopes had initially hinged on Western and Southern states. They presumed she would have a geographic advantage in Nevada’s Feb. 22 caucus and a demographic edge Feb. 29 in South Carolina, where black voters dominate the Democratic primary electorate. From there, they predicted a Super Tuesday jackpot March 3, seeing friendly territory in her home state of California and large numbers of African American voters in places such as Alabama and Arkansas.

The freshman senator catapulted into top-tier status after a commanding performance in the first debate. But subsequent mediocre debate showings, along with a murky ideological message, particularly on healthcare and her seesawing embrace of her prosecutorial past, hobbled her. By September, her campaign was forced to reboot, directing more attention on Iowa, home of the first Democratic nominating contest.

“I’m f—ing moving to Iowa,” Harris was overheard telling a fellow senator in September. Her campaign embraced the declaration, which ended up on a T-shirt sold by Des Moines retailer Raygun, known for its cheeky political merchandise.

The Hawkeye State became even more important after her campaign acknowledged last week it was laying off staff and slashing spending. Harris fired employees at her Baltimore headquarters, all but pulled out of New Hampshire and moved workers from Nevada and California into Iowa. In addition to ramping up its ground game in Iowa, the campaign is planning a seven-figure television ad buy in the weeks before the caucus. Her South Carolina team will stay in place.

“We have made a decision — a difficult decision — but made a decision of what we need to do to win,” Harris told reporters Wednesday.

It was a move her most ardent fans wished she’d made months ago.

“I was disappointed when she listened to people and stayed away from Iowa for a while,” said Doug Cameron, 71, a retired principal from Grinnell who backed Harris early on, drawn by her teacher pay proposal. “She needed to be here sooner than she was, make her presence known.”

But Cameron was optimistic that the redoubled efforts were moving the needle. “It may not be immediately obvious,” he said, “but the people I talk to are starting to come around.”

So far, Harris’ poll numbers in Iowa haven’t shown much improvement. A New York Times/Siena College poll released Friday showed her mired in the low single-digits, a world away from the upper echelon of candidates: Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., and former Vice President Joe Biden.

When a reporter noted that Harris had said in the past she considered herself a top-tier candidate, the California senator interrupted to firmly insist: “I still do.”

Kamala Harris delivered a well-received speech at the Iowa Democratic Party’s Liberty & Justice Celebration, a major organizing event in Des Moines.

(Joshua Lott / Getty Images)

Presidential primary history is filled with comeback stories, and Harris’ campaign was quick to point out that Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona in 2008 and Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts in 2004 were both forced to cut spending before notching resurgent victories and, ultimately, winning their parties’ nominations. (Both went on to lose the general elections.)

“A lot can change really fast,” said Grant Woodard, a Des Moines lawyer and Democratic campaign veteran, who worked on Kerry’s bid. “Three weeks out, I don’t think anyone in our campaign had a hope and prayer to win.”

Kerry’s victory was attributed in part to the snarling feud between the top contenders in the Democratic field that year — Vermont Gov. Howard Dean and Missouri Rep. Richard Gephardt. Voters irritated by the negativity turned to Kerry.

Woodard predicted that this year’s battle could get just as testy, particularly among the top-polling candidates. Harris could be the indirect beneficiary of the attacks, if she avoids becoming a target.

That possibility underscores the extent to which Harris’ fate is not entirely in her own hands. Even if she executes her Iowa strategy perfectly, her backers acknowledge she will still be at the mercy of waiting for her rivals to stumble.

Perhaps her biggest challenge is that voters can be fickle.

Dani Goedken, 18, was already a Harris supporter in September when she met the senator at the University of Northern Iowa, where she is a freshman studying pre-law and political communications. After the encounter, Goedken told a television reporter that she was even more sure she’d caucus for Harris.

But a few weeks later, her loyalties were torn. Warren had just held a rally on the campus in Cedar Falls, and Goedken found herself drawn to the Massachusetts senator’s ability to connect with younger voters. Her caucus plans, once certain, had become hazier.

“I can see myself being up for grabs,” Goedken said, “because I’ve gone back and forth with them so many times.”

Harris’ advisors say she thrives as a scrappy upstart, as she showed in her first race for district attorney in San Francisco. Facing a well-known incumbent, she set up an ironing board in front of grocery stores as a mobile desk to hand out fliers and introduce herself to voters. Now, in the smaller settings in Iowa, she is once again a tactile campaigner, warmly clasping well-wishers with both hands and fixing her gaze on them with laser focus.

In rural Newton, she stood in front of a living room fireplace — its mantle decorated with family photos and a colorful wooden parrot statue — and listened to Rose Evans fret that President Trump would not go gracefully from the Oval Office, even if he lost.

Harris, speaking directly to the retired teacher, promised she’d have the courage to take on Trump. With a self-deprecating reference to her diminutive stature, she puffed up her chest and assured Evans, “I’m really tall and big.”

“We need to put some Iowa beef on you!” Evans, 68, replied.

The interaction was enough to move Harris into Evans’ “top four,” she later said.

“She comes off much better in person — making the eye contact, talking to us — than she does on TV,” Evans said.

Not all voters were wowed. Laura Harreld, 62, pressed Harris at the Winthrop town hall on what could be done about homelessness in San Francisco, where the Democrat won two terms as district attorney.

“What was her answer? She doesn’t have a clear plan for that,” said Harreld, an interior designer from Strawberry Point. She demurred when a campaign staffer asked her to sign a card promising to caucus for Harris.

For an hour after her talk ended, Harris stayed in the Winthrop barn, wearing a jacket and scarf to ward off the chill as she chatted with voters. When nearly everyone had left, Harris remained, hunched over an ironing board signing placards and books.