Saeed Jalili and Masoud Pezeshkian will compete in Friday’s run-off presidential election in Iran, after no candidate won more than 50 percent of the vote in the first round, held on June 28.

The winner will become Iran’s new president, following the death of the late President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash on May 19.

Who are the two candidates left in the race?

The run-off will be contested by Saeed Jalili and Masoud Pezeshkian.

Jalili is mostly known internationally for his role in handling the Iranian nuclear file between 2007 and 2012, when he was the country’s uncompromising chief nuclear negotiator.

He currently serves as one of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s direct representatives on the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), and has unsuccessfully run for the presidency twice before.

Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon, has been a member of parliament since 2008, and was the deputy parliament speaker from 2016 to 2020. Apart from that, most of his government positions have been related to the health sector – he was a health minister in the early 2000s, and has been a longtime member of the Iranian parliament’s health commission.

He tried to run for the presidency in 2021, but was disqualified by the Guardian Council.

What political camps do the candidates represent?

Jalili is a conservative hardliner, in the mould of his former ally, the late President Raisi. An anti-Western figure, his role in the SNSC allowed him to operate what he called a “shadow government” during the moderate Hassan Rouhani’s period in office between 2013 and 2021.

Jalili was against the nuclear deal with the West in 2015, and would likely be unwilling to agree to Western terms to restore the deal if he became president. He has, however, promised to rapidly reduce inflation – even if he has failed to go into detail on how he would do so.

Pezeshkian, on the other hand, is considered to be a moderate, and has gained the endorsement of senior centrists and reformists within Iran’s establishment, such as former Presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani.

He says he will work to restore the 2015 nuclear deal, and has also expressed his opposition to the way the state has dealt with protests, including the nationwide protests that rocked Iran following the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, in police custody in 2022.

Which candidate represents Iran’s political establishment?

The first thing to note is that Iran’s political elite is not a single block, there are different power centres circling around Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Both Jalili and Pezeshkian are longtime members of this establishment and loyalists to the Iran government – even if Pezeshkian has more reformist tendencies.

Conservatives have tended to dominate Iran’s political establishment, particularly in recent years, and many have coalesced around Jalili.

Jalili and Pezeshkian are both supportive of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) – a pillar of the state’s military apparatus. Jalili is a former member of the IRGC, and Pezeshkian has demonstrated his support for the organisation in the past by wearing its uniform.

Pezeshkian has also demonstrated his allegiance to Iran’s political system by not supporting antigovernment protests, even if, as previously noted, he has criticised some aspects of the state’s response.

What was the result in the first round?

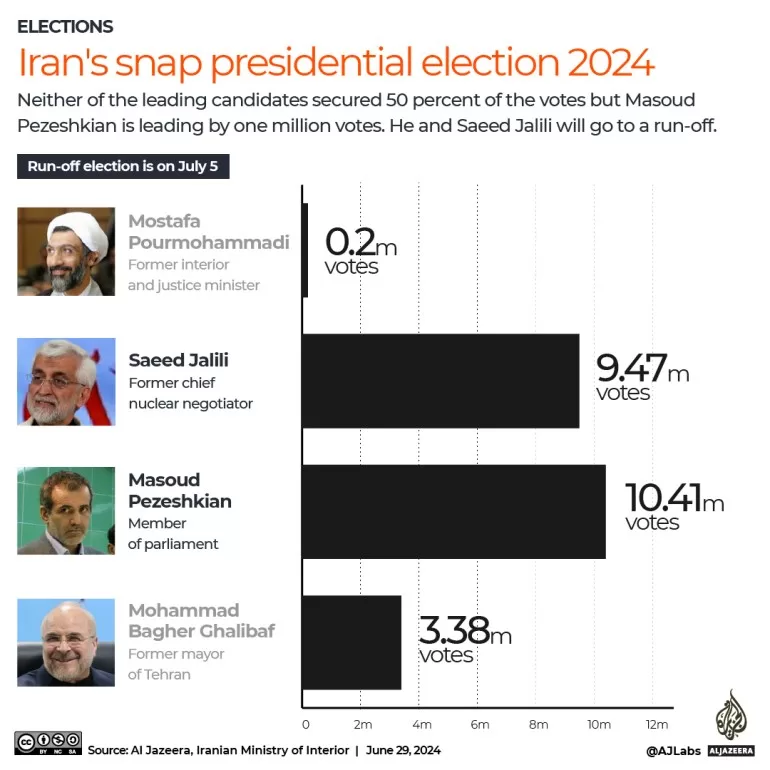

Pezeshkian came out on top, with 44.4 percent of the vote. Jalili got 40 percent, with the next highest candidate, the conservative former mayor of Tehran Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, getting 14.4 percent. As no candidate secured more than 50 percent of the vote, the top two candidates moved forward to a run-off.

The election saw a record-low turnout, with only 40 percent of the more than 61 million eligible Iranians voting.

Does that mean Pezeshkian is the frontrunner?

Not necessarily. Ghalibaf, along with two other failed conservative candidates who secured a small amount of the vote, have backed Jalili.

Pezeshkian’s chances rest on a higher turnout for the run-off, which can only be done by convincing enough centrist and reformist Iranians to vote.

On the one hand, many – particularly within the reformist camp – will be unwilling to participate in the country’s political system, especially following the state’s crackdown on the antigovernment protest movement. Pezeshkian’s continued support for the establishment may make many of them decide to stay at home.

On the other hand, the fear of a hardline Jalili presidency may convince some reform-minded voters to participate, even if they’re not fully convinced by Pezeshkian.

Pezeshkian’s chances rest on how many of those voters he’s able to sway.