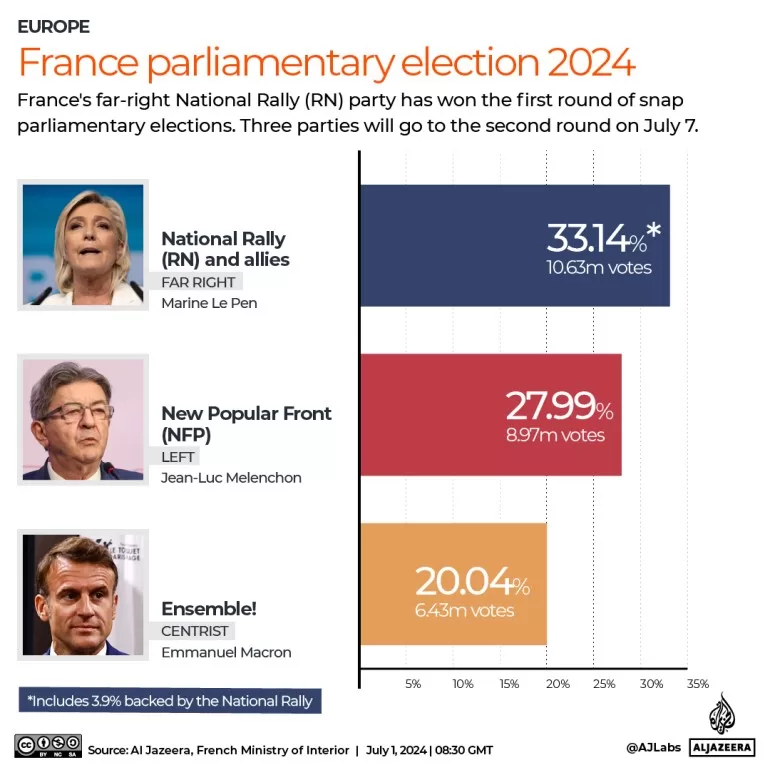

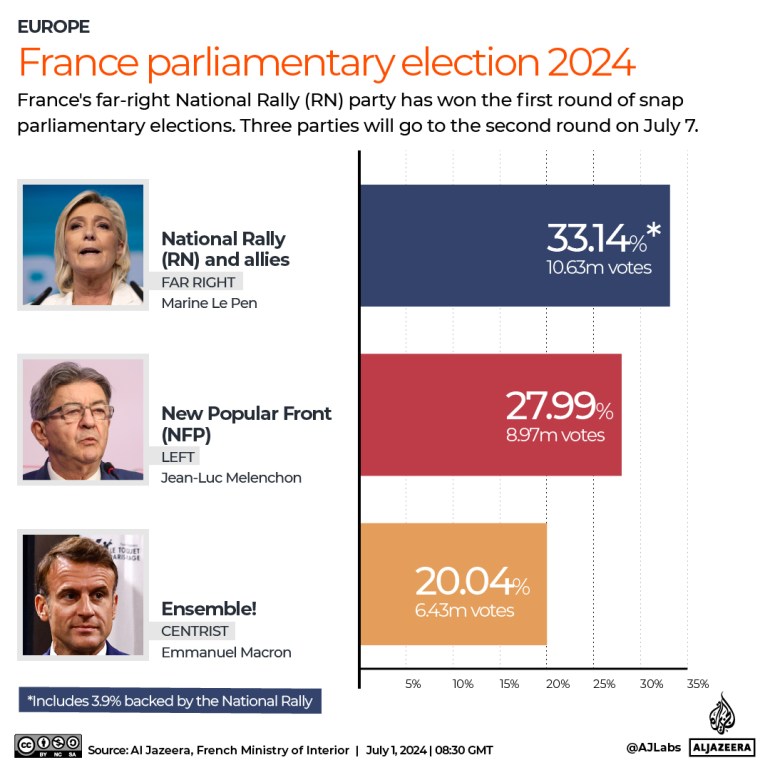

The far-right National Rally (RN) cruised to victory with 33 percent of the vote in the first round of voting last Sunday. But its hopes of winning an absolute majority have been dented after left-wing and centrist parties conspired to throw it off course by standing down candidates in some constituencies where votes could be split in the second round of polls on Sunday, July 7.

Faced with the prospect of the far right taking power for the first time since the Nazis occupied the country during World War II, parties from the left and centre have aligned in a so-called “Republican Front” to block the far right.

By Tuesday night, following frantic cross-party discussions, more than 200 left and centrist candidates had pulled out of constituency races in which they had finished in third place, hence averting any risk of the anti-RN vote being split in the final face-off.

On Sunday, French voters now face a binary choice between the leftists and centrists of the Republican Front on the one hand, and a far-right party rooted in xenophobia with a marked authoritarian bent on the other, in those constituencies.

Here’s the lowdown on how tactics are likely to play out:

What’s happening between the two rounds of voting?

Looking at the first-round results, Macron’s apparent bet that voters would baulk at the prospect of a radical right government clearly backfired.

The RN came out tops with 33 percent. The New Popular Front (NFP) – a hastily assembled coalition of left-wing social democrats and far-left anticapitalists – came second with 28 percent. And Macron’s centrist Ensemble (Together) coalition hobbled in at third place with 22 percent.

The unusually high voter turnout of 66.7 percent has paved the way for a more complex second round than usual, enabling more candidates to secure the 12.5 percent share of total registered constituency votes needed to get through to the next round.

With three-way contests projected in more than 300 of the country’s 577 constituencies, the anti-RN vote would have been split, potentially clearing the way for an absolute majority for the far right.

Now, following the tactical withdrawal of more than 200 candidates, that prospect seems more remote. Just 109 three-way or four-way contests will be taking place on Sunday.

“It’s real tactical voting with a broad brush,” Philippe Marliere, professor of French politics at University College London, told Al Jazeera. “Parties had to set aside their differences to deprive the RN of gaining a majority.”

However, he warned, the threat of a far-right victory is far from over. “It seems less likely that they will get a majority. But – and I would bet my mortgage on this – they could still win it.

“The stakes have never been so high,” he said.

Where does the far right stand now?

The National Rally (RN), formerly known as the National Front, has come a long way since it was set up just over half a century ago.

In this election, the party has seen its support surge beyond its traditional strongholds in the northeast and on the southern Mediterranean coast, sweeping up almost double the 18 percent of votes it won in 2022, a result that brings the party within touching distance of power.

Currently, the RN has 38 confirmed seats that it won outright in the first round of elections, six more than the NFP and 36 more than Macron’s centrists. With 76 seats in total won outright by various candidates, this leaves 501 seats up for grabs in the second round.

Andrew Smith, an historian of modern France at Queen Mary University of London, sees a number of “direct shootouts” in the Provence region between the far-left NFP and the far-right RN, “between the voices of urban centres and the suburban sprawls with supermarkets and industrial estates”.

“Often RN voters support law-and-order politics, complaining about the sense that crime is out of control, that there’s youth delinquency, gangs and drugs. The other discussion would be immigration. The two things are linked in the rhetoric of the National Rally,” he says.

RN needs 289 of the 577 seats in the National Assembly to form the absolute majority that will elevate its youthful president Jordan Bardella to the rank of prime minister, enabling the party to drive forward its hardline anti-immigration agenda unimpeded.

Even if the RN does not win a majority on Sunday, it is still expected to emerge as the dominant party in the French parliament.

Will voters heed the Republican Front’s pleas?

With French politics increasingly polarised over issues like state benefits, corporate taxes and the policing of protests, it remains to be seen whether left-wing and centre-right voters will be open to transferring their votes to candidates they often actively loathe to keep out the far right.

Many may simply opt to stay at home.

Marliere reckons Macron’s camp missed the point, intimating before the first round that a vote for the far-left France Unbowed (LFI) party – part of the NFP alliance – was as dangerous as a vote for RN and could push the country towards civil war.

“It is only in recent days that Macron and [Prime Minister Gabriel] Attal came out more strongly in support of the Republican Front whatever the situation, including voting for LFI,” he said. “They were reluctant to do it.”

Macron could come to regret his carping about LFI – most recently rejecting the possibility of allying with the far-left party as part of a broad-based coalition – if abstentions end up swinging the vote in the RN’s favour, observers say.

Seen from the left-wing camp, the president himself is not popular. Many reject his attempts to position himself as a bulwark against extremism, criticising his Davos-friendly reforms and his heavily personalised, somewhat out-of-touch leadership style – most recently exemplified by his decision to spring a snap election on the nation as it prepares to host the Olympics.

“For many voters, this is kind of a stitch-up,” said Smith. Voters, he said, have noted the topsy-turvy scenarios thrown up by the Republican Front, with former Prime Minister Edouard Philippe, a leading figure in the pro-Macron camp, pledging to vote for a communist candidate.

In a similarly unbelievable vein, the LFI’s Leslie Mortreux pulled out so that hardline Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin – hardly a darling of the left – could face off against the far right in the 10th district constituency in northern France.

“This is very much the attack line of Marine Le Pen,” Smith told Al Jazeera. “She’s been very clear about the fact that [the Republican Front] is producing unusual things.”

Le Pen took to X to denounce the tactical manoeuvring. “The political class is giving an increasingly grotesque image of itself,” she said on Wednesday.

What’s the likely outcome?

“There’s far less chance now of a thumping majority,” said Smith.

Poll results on Wednesday indicated that the tactical withdrawals will prevent the RN from winning the absolute majority it needs to fast-track policies like abolishing the “droit du sol” – the automatic right to French citizenship for children of immigrants born in France – and banning headscarves from public places.

Le Pen has said she could reach out to other parties if the RN falls short of an absolute majority – most notably the conservative Republicans (LR) party, whose leader Eric Ciotti unilaterally lent the party his backing, prompting a backlash from his party.

But Wednesday’s polling, conducted for Challenges magazine, predicted that the RN and LR would lack the combined heft to control the 577-seat National Assembly.

In any case, RN prime ministerial pick Jordan Bardella has already said he would decline to form a government without a sufficiently strong mandate.

In the more probable event of a hung parliament, politicians across the spectrum have proposed various ways of proceeding. Xavier Bertrand, a senior member of the centre-right LR party, called on Tuesday for a “provisional government” to run France until the next presidential election.

However, Prime Minister Attal on Wednesday rejected the idea of a cross-party government, suggesting mainstream right, left and centre parties could form ad hoc alliances to vote through individual pieces of legislation in the new parliament.

Even if the far right does not come to power in this election, the country faces months of political uncertainty until the end of Macron’s term in 2027, when RN’s Le Pen is widely expected to mount a challenge for the presidency itself, say observers.

Said Marliere: “It’s a big mess politically. We might be in political blockage for one year.”