The Canadian actor worked on a wide and varied body of films across many genres, including “The Dirty Dozen,” “MASH,” “Klute,” “Don’t Look Now,” “Animal House,” “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and more recently the 2005 adaptation of “Pride & Prejudice” and the “Hunger Games” franchise.

Julie Christie appeared alongside Sutherland in Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film “Don’t Look Now,” an emotionally devastating portrait of a couple struggling to overcome the death of their young daughter.

In an exclusive statement to The Times, Christie said, “Donald’s unique intelligence and mischievous humour is what elevated him and rendered him so fascinating as an actor.”

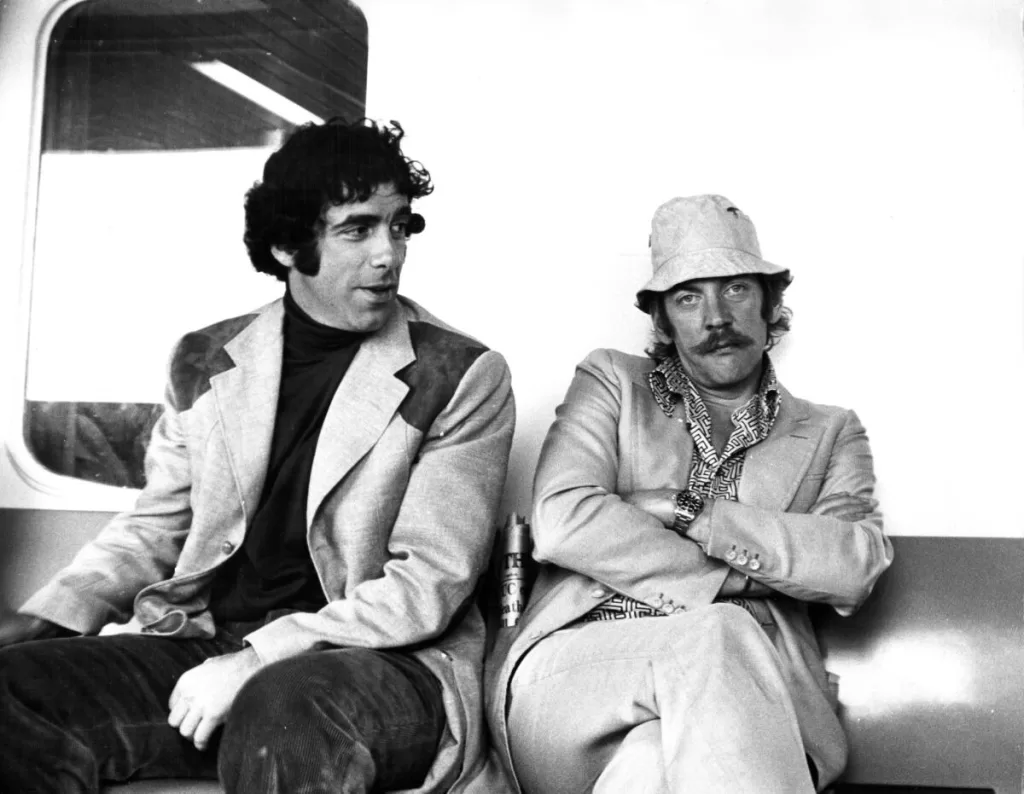

Arguably few performers are as closely aligned with Sutherland as Elliott Gould, as the two co-starred in Robert Altman’s 1970 anti-war dramedy “MASH,” which launched both actors to new levels of fame.

They subsequently appeared together in 1971’s dark satire “Little Murders,” directed by Alan Arkin from the play by Jules Feiffer and produced by Gould, as well as 1974’s espionage comedy “SPYS,” helmed by Irvin Kershner.

Reached by phone on Friday, Gould reflected warmly on his work with Sutherland.

(Stanley Bielecki Movie Collection / Getty Images)

I am so honored to be talking to you, but I regret so much the circumstances under which we’re speaking.

No, I see it differently. It moves me so. I see that I can be sad for us, but that we are celebrating the magnificence of this human being, Donald Sutherland, who I had such a privilege to work closely with, I feel it’s not a loss, it’s a gain.

When you think of Donald, what first comes to mind for you?

The pros from Dover. That was Donald. He made us the pros from Dover in “MASH.” Oh my God, I don’t know anyone like Donald. I’d seen him in film, but that was pretty early. It was basically “The Dirty Dozen.” And when Bob Altman asked me to have lunch. Once he cast me to play opposite Donald, he asked me to have lunch alone with Donald at the commissary of 20th Century Fox. I went there and just sat down with Donald, and my first feeling was, “Oh, I don’t think this guy likes me.” And, of course, we got to be so close and made amazing chemistry together as two utterly opposite human beings. I’ve never worked with better. He’s my brother.

Where do you think that chemistry came from? How would you describe it?

Our relationship was all about nature, human nature and being a human being. And we never intellectualized about it. We couldn’t have been more diverse. As far as I’m concerned, so long as I’m living, Donald will always be with me.

When you started working together on “MASH,” was that energy between the two of you apparent right away? In your first scene in the movie, you don’t say much and he can’t stop talking. It’s incredible.

And, of course, never neglect Tom Skerritt or any other amazing elements from the picture. But the way we shot it, I recall the first time that Lew Alcindor [Kareem Abdul-Jabbar] played against Wilt Chamberlain, that Altman was screening the picture for the whole cast at 20th Century Fox. And we may have seen it, because I think they may have had a sneak preview in San Francisco, but I don’t like to speculate. And so I was showing Donald a game that I learned on the streets of Brooklyn, New York, which was called “against the wall.” You played baseball against the wall. And it was just me and Donald. And we didn’t go in.

We also stayed really separate. Everybody was with Altman. We worked for Altman, there’s no question or doubt about that, but we were pretty much segregated other than in the scenes. And Ring Lardner, Jr. stepped outside after the screening and walked up to me, and I thought, “What are you walking up to me? I’m just acting here.” And Donald, of course, was with me because we were always together. And Ring Lardner, Jr. said, “How could you do this to me? There’s not a line I wrote that’s on-screen.” And Ring Lardner went on to win the Academy Award that year for the best screenplay. Of course, that was due to the brilliance and genius of Robert Altman. But Robert Altman put us together and allowed us to make a chemistry the likes of which I’ll never know again.

“MASH” was really the first time audiences saw what became Altman’s signature style with the chaotic energy, overlapping dialogue and the restless camera. Was it hard for you and Donald and the other actors to get in sync with that process?

Absolutely. And Donald and I complained once. I had never worked like that. I had participated in three films before then, which I remember quite clearly, but I’d never improvised on film. And as far as information or what dialogue transports, what it serves, Donald and I complained about Robert Altman, which, of course, was horrible for Bob. Bob thought we wanted him fired, which is totally untrue. We were just uncomfortable in that way of work. But then Bob reshot something, which exhibited to me that he was willing to work with us and allow us to be the actors that we were. And the rest is history.

Elliott Gould, from left, Tom Skerritt and Donald Sutherland in “MASH.”

(20th Century Fox)

The success of “MASH” made both you and Donald much bigger stars in the moment. Was it good for you to have someone there who was having that same ride at that same time? Did you feel the two of you were going through that moment together?

I don’t want to be sentimental, I don’t want to be pretentious. People perhaps make intellectual justifications out of anything, but Donald and I were together, and I even believe now that he’s out of body and not here any longer other than with those of us where his spirit lives. When we were going to do “SPYS,” which was another title, and it had been conceived for two other actors, the other actors being David Niven and Carroll O’Connor, two washed-up CIA agents. And it was sent to me, and I turned it down.

And this would be the only time, or one of the very few times, that Donald ever called me. And he called me to say, I understand you turned down “Wet Stuff,” which became “SPYS.” I said, “Yes, I didn’t think the script was up to the idea of the story.” And Donald then said to me, “Would you make it with me?” And I said, “You mean you would make this with me?” And he said, “Yeah.” I said, “Well, that’s a different story.” We make chemistry, our chemistry. I said, “Of course, I’ll do anything together with you.” And then Irvin Kershner was the director, and I grew to love Kershner, and then they got the right people to rewrite it. They never talked with me in relation to the rewrite. And it’s not about me, but I have this instinct. And so they rewrote it.

And now we were in London, and this was the first day of shooting “SPYS,” and it wasn’t even called “SPYS” yet, and Donald and I were being driven in a fancy car to where we were going to shoot the first day’s work. And Donald asked me what I think of this script. And I said, “It’s a piece of s—.” I rolled the window down and I threw the script out the window. I said the only way it can work is if you play the part they think I’m going to play, and I play the part they think you are going to play. We might be able to do something. But the producers, who were extremely successful producers, Bob Chartoff and Irwin Winkler, they couldn’t hear of it. And so we did the picture. But our history in film, I always wanted to make another film with Donald.

Tell me about his part in “Little Murders.” You produced that picture as well and he comes in to deliver this incredible monologue during a wedding scene. What made you want Donald for that part?

He was perfect. We were doing the picture, I produced it; I had done the first version of it on stage and Jules Feiffer is a friend of mine. And we asked Donald to do it, and he did. I think we paid him $5,000 to do it. Of course, that was another time and things were cheaper. But Donald was unbelievable in it. And I remember he had a cold — he came to work, he had a cough. And I walked around the corner, because the church that we shot in is there in Manhattan. I got him some fresh squeezed orange juice. And Donald played that character beyond belief. Donald Sutherland in “Little Murders.” Wow. It doesn’t get better.

Do you have any favorite performances of Donald’s besides the work that you did together?

The last shot of his “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” is terrifying. Just that last silent dream of his is quite something. And “Pride & Prejudice,” because it touches me. Donald came really deep here. His performance in “Pride & Prejudice,” to me, it is absolutely magnificent.

In recent years, he found a whole new audience with his appearance in the “Hunger Games” pictures. And it’s similar to what you experienced when you were on “Friends,” a whole new generation discovering you as a performer. It’s so great that both of you had a similar kind of explosion later in your careers.

Or a part of an explosion. I played a little basketball with Donald and he didn’t play basketball, but he was a giant and he had big hands. And, of course, he came from a different culture. We couldn’t have been more different, which was amazing for the chemistry that we made. He was so generous, so sensitive, so kind and such an asset. He showed me “Don’t Look Now” in London and I showed him “The Long Goodbye” in London. We never hung out too much. I think that Donald possibly, probably, did more work than me, but I don’t know. We deeply, deeply bonded on “MASH” and, agreed, he told me that we were brothers.

I like so much the idea of you sharing your films with each other, especially those two, which are really iconic works for each of you. There’s something really wonderful about that.

Well, Donald Sutherland was wonderful. And as far as I’m concerned, we were wonderful together. I remember when Donald did “Alex in Wonderland,” which [Paul Mazursky] really wanted me to do. And in the scene where Donald takes Jean Moreau on a horse and buggy with the music from “Jules and Jim,” I started to weep. Donald’s sensitivity. The gift of working as closely with Donald Sutherland and for us to get to know one another, utterly opposites who merged in the work in perfect chemistry.