They share many other similarities as powerful Democrats leading California’s marquee cities: a promise to reduce homelessness; plans to mitigate an opioid overdose crisis; an electorate concerned about crime.

But the ways the two mayors are attacking those urban problems reveal some surprising differences between them.

Breed, 49, has backed a tough-on-crime statewide ballot initiative that Bass, 70, does not support. The San Francisco mayor has also worked to toughen criminal penalties for fentanyl dealers and require drug screening and treatment for certain welfare recipients — issues the Los Angeles mayor has not weighed in on with financial assistance overseen by the county.

And they are split over a high-profile Supreme Court case that could make it easier for cities to clear homeless encampments: Breed has welcomed the high court’s review while Bass warned against a ruling that “could embolden those who wish to criminalize unhoused Angelenos.”

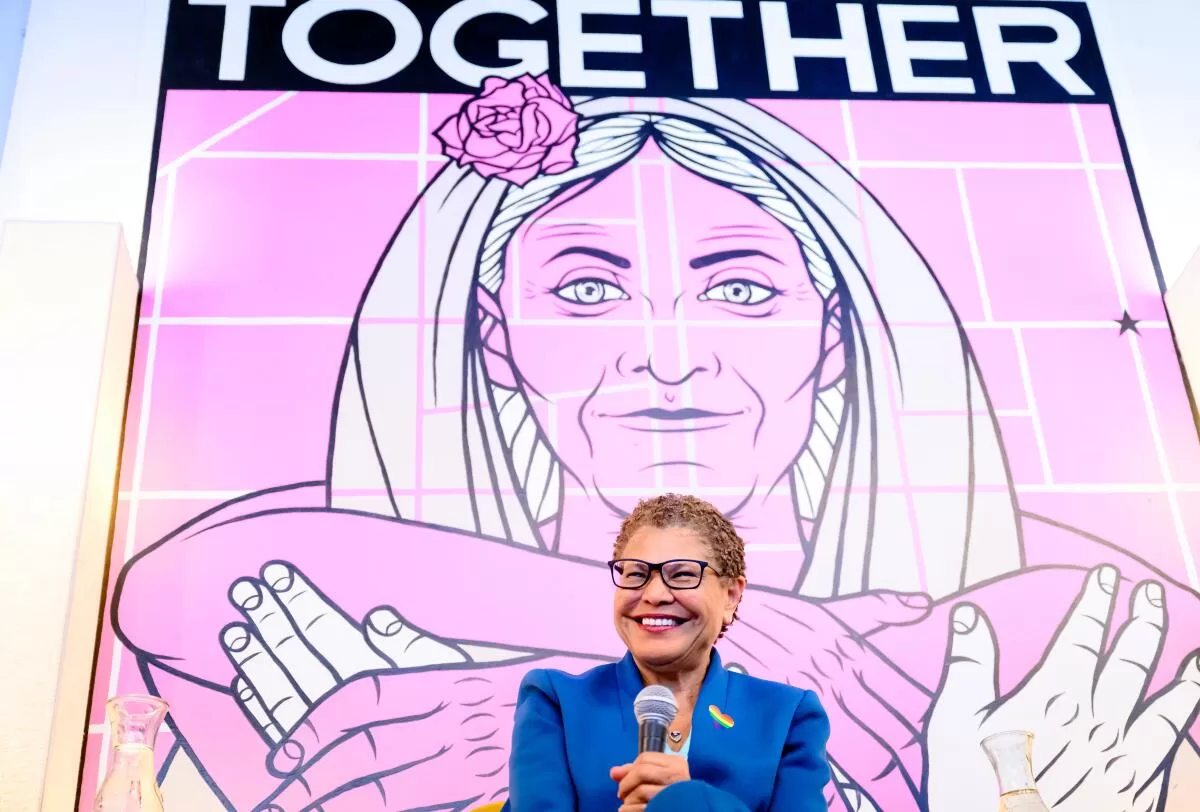

“Homelessness is the reason I ran,” Bass said during a discussion Monday at the civic engagement cafe Manny’s in San Francisco. “The main thing is getting people off the street ASAP because people are dying. But the problem in L.A. is the massive numbers.”

It was the first time the two mayors came together publicly for a one-on-one conversation. They discussed the challenges they face leading California’s most famous and influential cities.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

About 46,000 people are homeless in Los Angeles, where the population is about 3.8 million. An estimated 8,323 people are homeless in San Francisco, a city of about 808,000.

Breed said the problem in San Francisco is “a little bit different.”

Though the city has increased shelter capacity and helped 15,000 people exit homelessness, Breed said, the city faces a conundrum: The number of people who refuse housing or shelter is growing.

“The biggest problem is fentanyl, is drugs,” she said. “That has been the biggest challenge we’ve had to get people off the streets.”

Political differences in L.A. and S.F.

Breed and Bass are at different points in their mayorships, which may explain some of their divergence on policy. After six years leading San Francisco, Breed is up for reelection this year in a tough race against four serious challengers.

In contrast, Bass, who referred to herself as a “rookie” Monday, is still in a honeymoon phase after winning the election in November 2022.

“There seems to be this kind of doomy narrative in San Francisco that I don’t feel is quite as front of mind for Angelenos,” said Jason Ward, an economist at Rand Corp. in Santa Monica.

Mayor London Breed has supported some tough-on-crime strategies to address street homelessness and open-air drug use in San Francisco.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

As Breed’s political challenges have mounted in the last two years, she has turned to tough-on-crime strategies to crack down on street homelessness, open-air drug use and other public safety issues she once described in a speech as the “bull— that destroyed our city.”

Bass has sought a compassionate approach to homelessness without losing the support of the business community, a strategy that’s drawn praise and criticism. She has not given an endorsement in the heated L.A. district attorney race, which pits a so-called law and order candidate against the progressive incumbent.

In some instances, the two politicians are bringing the same blueprint to solving their cities’ problems.

Breed declared a state of emergency in December 2021 for the drug-infested Tenderloin district, with Bass following suit a year later with her own emergency declaration on homelessness. Both efforts aimed to make it easier to get people off the streets and increase access to resources.

Both mayors have rejected calls to roll back funding for police, even adding money for law enforcement in their city budgets, despite objections from some left-leaning voters. And they’ve each focused much of the last year on addressing homelessness via temporary shelter beds, while also putting money toward addiction and mental health services.

But it’s their policy differences that illustrate the varied ways civic leaders are trying to solve some of California’s thorniest problems.

“This is the nice thing about more and more women getting into elected life,” said Elizabeth Ashford, a Democratic strategist and board member of California Women Lead, an organization that works to elect more women. “People are going to have to rise and fall based on their own merits as leaders.”

As Black women, both mayors said their identities shape their experiences as politicians.

Bass said L.A.’s Black population is “quite small” at about 8%, and because of that she believes people misjudge her.

“I don’t mind being underestimated,” she said. “They won’t see it coming!”

San Francisco Mayor London Breed and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass discuss their cities’ challenges at Manny’s cafe in San Francisco.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

Breed echoed those same hurdles leading San Francisco, where the Black population is less than 5%.

“I’ve had to have some really hard conversations with a lot of very privileged people in this city who feel comfortable talking to me as if I’m beneath them,” Breed said.

“As African American women leading major cities, it’s different. Everybody wants the mayor to do a good job, but sometimes the challenges we face are different.”

Different approaches to fighting crime

Breed earlier this year endorsed a GOP-backed measure proposed for the November ballot that aims to roll back part of Proposition 47, a 2014 voter-approved initiative that reduced certain theft and drug felonies to misdemeanors. The measure would increase penalties for fentanyl dealers and organized retail theft rings, and provide mandatory treatment for drug users.

Bass said she doesn’t support efforts to repeal Proposition 47.

She said in a statement to The Times that the law “has its strengths and weaknesses and it should be evaluated in the same way that the impacts of any policy should be examined,” though her office didn’t make clear how she thinks the policy should be analyzed.

The mayors’ approaches “couldn’t be more different,” said Anne Irwin, director of Smart Justice California, a group that advocates for progressive changes to the criminal justice system.

Bass has “taken the lessons from the tough-on-crime era and accepted the hard truth that it didn’t work,” Irwin said. Breed, she said, has reverted to a “familiar political rhetoric” that appeases voters in the short term but fails public safety in the long haul.

“That’s why I call it an easy, expedient response,” Irwin said. “But that’s not leadership.”

While Irwin acknowledged that many San Franciscans want to see a tougher approach on public safety issues, she attributed waning voter support for Breed to what she described as an inconsistent and chaotic approach to solving those problems.

“San Franciscans are watching Mayor Breed over these past several years lurch from one approach to another based on the loudest headlines that week,” Irwin said.

People outside the event protest budget cuts Mayor London Breed has proposed in San Francisco, including funds for child-care programs and food banks.

(Josh Edelson / For The Times)

To Breed’s supporters, she is making tough decisions for a city she loves.

Breed grew up in the Western Addition, raised by her grandmother in a tough childhood defined by poverty, gang violence and street crime. She has shared the story of losing a sister to a drug overdose nearly 20 years ago, and her brother has served more than two decades in prison for armed robbery and other charges.

“London Breed has a ton of experience being exposed to that kind of a life, and I would think that she has reacted in the way she should for the safety of her citizens,” said former Mayor Willie Brown, who made history himself as the first Black mayor of San Francisco and, before that, as speaker of the state Assembly. “And that’s what would be expected of a mayor.”

Bass has spent much of her time in office so far as she promised on the campaign trail — almost exclusively focused on homelessness. Under Bass’ Inside Safe program, which places homeless people in hotels, motels and other forms of shelter, 2,720 people have been moved from street encampments, according to officials.

She also issued an order that has dramatically sped up the city’s approval of residential projects deemed 100% affordable. In April, she said that more than 16,000 affordable housing units had entered the city’s pipeline.

Bass was raised in the Venice-Fairfax area of Los Angeles, and was volunteering for Sen. Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign by age 14.

She founded Community Coalition, a nonprofit focused on tackling the structural racism that led to neglect in South L.A. A former emergency room physician assistant, she served more than a decade in Congress before being elected mayor.

She has sought to walk a fine line between helping people get into shelters and housing and responding to complaints from businesses and neighbors about tents and drug use.

She has mostly stayed out of the debate over a policy that gives council members the option to bar homeless encampments within 500 feet of schools and parks. The law is attacked by the most left-leaning members of the City Council, who decry it as a waste of police resources.

Bass, in interviews, has suggested that the law simply shuffles homeless encampments around, but said she won’t seek to repeal it.

The way the two mayors are responding reflects the frustrations in their respective cities, said Sam Tsemberis, chief executive of the Pathways Housing First Institute in Santa Monica.

“It comes down to personal attitudes and values,” Tsemberis said. “And also for the politicians, what will play well in terms of the likelihood of their reelection.”