Sacramento lawmakers have been bombarded with ads and pitches in support of a ballot proposal that would have the state borrow as much as $10 billion to fund projects related to the environment and climate change.

“Time to GO ALL IN on a Climate Bond,” says the ad from WateReuse California, a trade association advocating for projects that would recycle treated sewage and storm runoff into drinking water.

“Invest in California’s Ports to Advance Offshore Wind,” says an ad by the companies that want to build giant wind turbines off the coast.

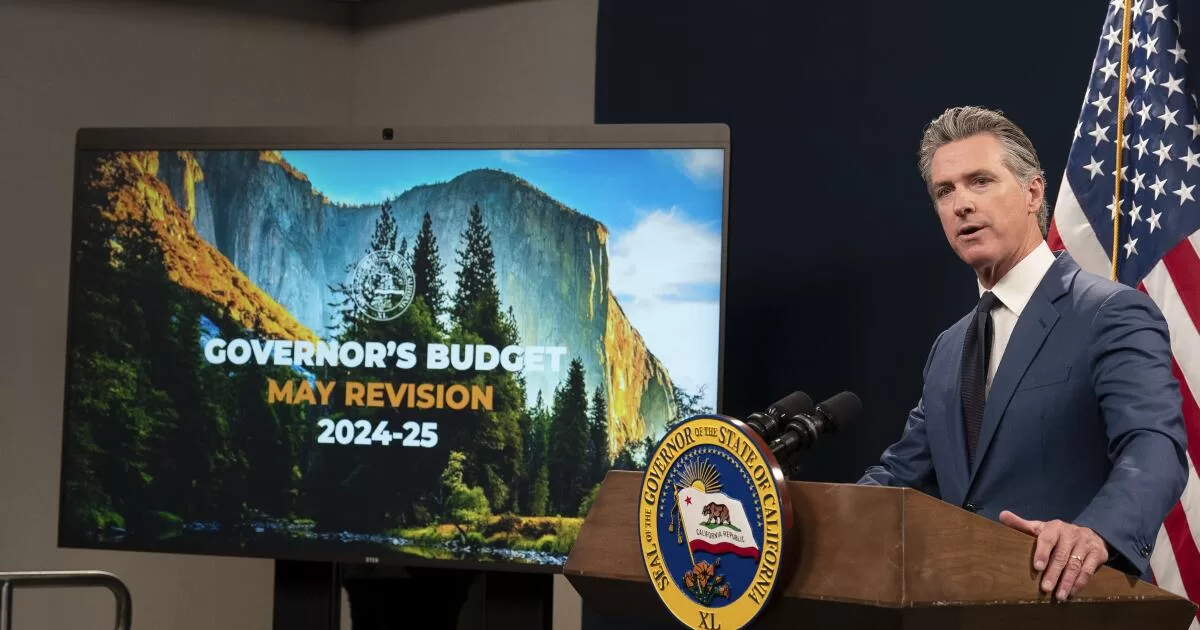

The jockeying by the lobbyists to get their priorities into the proposed climate bond measure intensified after Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed spending $54 billion on climate in 2022 but then cut that funding to close recent massive budget deficits.

If approved by lawmakers, voters would decide in November if they want the state to borrow the money and pay it back over the decades with interest.

“The science and the economics clearly show that prompt climate investments will save Californians money and maximize the effectiveness of adaptation options intended to benefit people and nature,” said Jos Hill at the Pew Charitable Trusts. The nonprofit is part of a coalition of 170 groups, including those advocating for environmental justice and sustainable farming, that is lobbying for the bond.

Negotiations are ongoing in closed-door meetings, but details emerged recently when two spreadsheets of the proposed spending, one for an Assembly bill known as AB 1567 and the other for the Senate’s SB 867, were obtained by the news organization Politico.

The two plans, which would be combined into a single ballot measure, include money for wildlife and land protection, safe drinking water, shoring up the coast from erosion and wildfire prevention.

They also include hundreds of millions of dollars for projects that would benefit private industry, including some green energy companies that are already benefiting from the gush of federal money aimed at mitigating global warming coming from President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

A final decision of whether to include a climate bond on the ballot must be made by June 27. The proposal is competing with plans to borrow money for other issues, including school construction. And lawmakers have said they don’t want to overwhelm voters with too many pleas to take on more debt.

Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia, a Democrat from Coachella and the author of AB 1567, told The Times this week that negotiators were favoring a climate bond that would borrow $9 billion.

Both the Assembly and Senate plans include hundreds of millions of dollars to build facilities at California ports to support the development of offshore wind farms.

“The conversation is,” said Garcia, “how do we support infrastructure at the ports that can help offshore wind get off the ground?”

And $100 million or more, according to the spread sheets, would go to building electric transmission lines needed to connect green energy to the grid. Already Pacific Gas & Electric and the two other big electric companies have recently hiked electric bills to pay for building and maintaining transmission lines.

Sen. Ben Allen, a Santa Monica Democrat and author of SB 867, said the numbers in the spreadsheets should not be counted on, including the amounts for electric transmission, because negotiations were continuing.

“This is public money,” Allen said. “This is not about making life easier for utilities.”

Governments often take out long-term debt to pay for infrastructure projects that are expensive to build but will last for decades. Yet some of the planned climate bond spending, according to the spreadsheets, would go to operate day-to-day programs that could long be over when the bonds are finally paid off.

For instance, the Assembly spreadsheet has $500 million going to “workforce development” or the training of people to work in the field of clean energy.

Garcia said that many items in the spreadsheet had been changed in the negotiations, but he declined to give more details.

Allen said the focus was on long-term investment. “The key thing with a bond is ensuring that you’re focused on investments that truly have a long-term benefit because you are going to be asking people 25 years from now to pay for the investments that we’re putting in place this decade. So that’s got to be a guiding principle.”

Earlier this year, Sacramento legislators had proposals to place tens of billions of dollars of bonds on the November ballot, funding efforts including stopping fentanyl overdoses and building affordable housing. But those plans were crushed in March when a $6.4-billion bond measure promoted by Newsom to help homeless and mentally ill people got 50.18% of the vote, just barely enough to win approval.

The measure, known as Proposition 1, will pay for new homes and treatment places for mentally ill people, and cost the state $310 million a year for the next 30 years.

Legislators are now debating what additional proposed bonds are most likely to pass on the November ballot. They are also considering the state’s debt service ratio, which is the percentage of the general fund that must go to pay down the debt.

A large jump in the debt service ratio could harm the state’s credit rating. Currently California’s credit rating falls in the middle of the pack among the 50 states. Texas and Florida are among the better rated states, while Illinois and New Jersey are among those with lower ratings.

David Crane, a lecturer at Stanford and the president of Govern for California, pointed out that required payments on bonds that the state has already issued, as well as mandatory payments for employee pension obligations and retiree health insurance, “crowd out spending on other programs.”

“If they are going to add to that burden with another bond,” he said, “they should make sure the money is well spent.”

In a February report, the Legislative Analyst’s Office said the Newsom administration had been spending unprecedented amounts of money on climate and the environment but said there was little information on how effective it had been.

“The lack of such information,” the report said, was hampering “longer-term decisions, such as… which programs should be prioritized for future funding.”

It is already clear that groups maneuvering for a share of the proposed bond money will not get all they have requested.

In California, where fights over water supplies have been ongoing for decades, lobbyists representing water agencies across the state are asking legislators for two-thirds of the proceeds.

Among their requests are $1 billion for water recycling and desalination projects, $500 million for water quality and clean drinking water upgrades, $950 million for flood protection and $700 million to improve dam safety.

“For California to be prepared for longer droughts and be prepared for extreme precipitation events, the state needs to invest more in water infrastructure funding, and general obligation bonds are a good way to help fund infrastructure,” said Cindy Tuck, deputy executive director of the Assn. of California Water Agencies.

“The cost of these projects are not going down,” Tuck said. “With inflation, the costs are going up. So it really makes sense to invest now in water.”

Newsletter

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.