In 1992, two fresh photography grads were enchanted by the idea of a fresh artistic space devoted to the community and the burgeoning culture in the city.

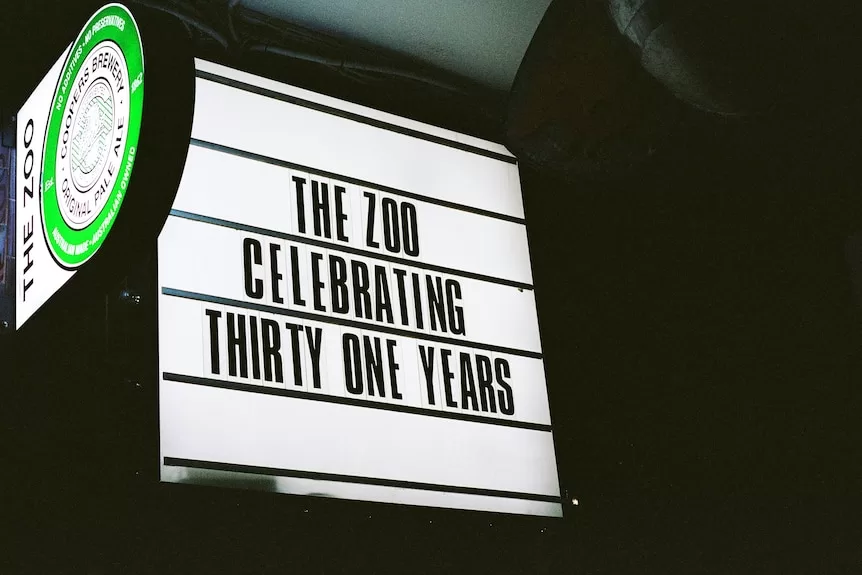

Armed with an idea, Joc Curran and C Smith used a $5000 grant from the federal government’s New Enterprise Incentive Scheme to open a welcoming, sweaty, and truly unique space for music and the arts — The Zoo was born.

They were 23 and 25 years old, young women taking on the venue.

Hindsight proves conditions were perfect for the birth of The Zoo, which would go on to serve music lovers for more than three decades.

History of The Zoo

Ben Green, a cultural sociologist at Griffith University, said The Zoo popped up at a time when Fortitude Valley — and Brisbane itself — was going through some big changes.

For years, the Valley had been a hotbed of crime and police corruption.

This changed with the Fitzgerald Inquiry and the end of the Bjelke-Petersen years, and the area began to undergo a metamorphosis — it’s into this new world that The Zoo was born, a space revitalised and re-adopted by the Brisbane community.

“It was just after a previous version of the Valley had ended,” Dr Green said.

“So when that ended, and then the 90s saw this new rebirth, The Zoo was really a crucial part of that.

“It became a hub for the cultures that thrived in the Valley.”

Much was made of the early days of The Zoo, the BYO alcohol, and the veggie curries that were a requirement of the venue’s cheap-as-chips liquor licence.

Photos from the venue can’t be mistaken for anywhere else; eclectic is the word.

From the industrial atmosphere to the fish-and-chip shop bar fridges — the tall-wide windows, the water bubbler in the corner — the place has a personality to it that couldn’t be planned, aped, or created by committee.

It was built by 30 years of passion, by the thousands of Brisbanites who sweated, screamed, and danced on its sticky floors.

“It’s the buzz, it’s the vibe of the place, to quote The Castle,” Double J broadcaster Costa Zouliou said.

“You know, you go up those stairs, and you leave all that sh*t in Ann Street behind. You walk up those stairs and you’re in a different world.”

These are examples of the quirky personality behind the venue, but it also hints at just how many hoops need to be jumped through to run a venue of any size or purpose in Brisbane.

These weren’t hoops that went away with time; The Zoo might have been able to ditch its curries at a point, air-conditioning might now be standard instead of oppressive heat, but it was never made easy for proprietors.

“The cost of touring has gone up, and therefore the fee that an artist charges has gone up, especially at national and international levels,” Dr Green said.

“Therefore — whether you’re a venue or whether you’re a festival promoter — you need to pay them, and that cost has gone up significantly in the last few years as well.

“So on all fronts, the costs of running a live music business have gone up.”

The missing link

Among musicians, there’s a sense of disappointment that a town that plays host to Bigsound each year — the southern hemisphere’s equivalent of the United States’ SXSW — seems to be moving away from its local roots.

Without those roots, it seems like a given that bands — like Powderfinger, Violent Soho, Ball Park Music and Custard — just won’t be able to hack it any more.

These bands graduated from little bars to The Zoo, up to bigger venues, before taking over the country.

Patience Hodgson, whose band The Grates got their start playing Ric’s and The Zoo, said there was a missing link in the pipeline without such venues.

She knows the role The Zoo played on the road to creative success in Brisbane.

According to her, things will start to get really difficult without that middle rung.

“For some bands coming up, with a little bit of hype, [500 tickets] is a really accessible number,” she said.

“It’s just such a good step to be able to work up, slowly build up until you can hit and it’s great — you’re doing 500 people sold-out, and that means something when you’re going on tour.

“If you tell booking agents in other cities you’ve sold out The Zoo, they know what you’re talking about.”

Dr Green agrees The Zoo’s closure leaves a worrying gap in the scene — it’s no drama for international tours to book out the Entertainment Centre, Riverstage, or one of the stadiums, but local bands still working a day job can still hit the Junk Bar, the Bearded Lady, or Black Bear.

But where do they go from there?

The bridge from the 200-capacity venues has been consumed by the rising tide, and the jump to The Triffid at 800-capacity is often just too much for local bands who are trying to make their name.

“It’s interesting now that, due to the very success of that entertainment precinct, live music is one of the things that’s been gradually edged out from other forms of entertainment — that’s kind of ironic,” Dr Green said.

“One of the things I found in my research with musicians in Brisbane is that they will always talk about their first gig at The Zoo as a real key moment, for them a peak moment in their career.

“The first time they played The Zoo, or the first time they sold out The Zoo, it’s always had that iconic status for people.”

Closing down The Zoo

There’s something so communal about the Brisbane music industry; anyone that’s ever worked or played in the space, run events, washed glasses, or played on stage will understand.

People know each other, they like each other. It’s as simple as that.

Mr Zouliou said it was a palpable community in a way that many other cities could only dream of — people just have each other’s backs.

“The Brisbane music scene had, and hopefully still has, a real camaraderie about it,” he said.

“So if someone’s amp broke, or the string broke on a bass guitar, people from here go ‘use my amp, use my guitar tonight’, and those local bands would just keep filtering and bubbling through.”

That all-in-it-together mindset was on full display on Friday night at the aptly named “Zoolove”, the final farewell from this important Brisbane venue.

Zoolove was a distillation of everything The Zoo has come to signify: familiar, positive, and moving — beer flowed, much of it onto the floor.

A constant stream of musicians took the stage, bouncing off one another and celebrating music and community.

Between acts, impromptu dance circles and drumming performances kept the energy up, while the people who built this community with love and string-callused fingers chatted about all the things they’d seen and done at The Zoo.

It’s hard not to watch two members of Powderfinger, who grew up in The Zoo as much as any other band, slam through a rendition of ‘(Babe I’ve Got You) On My Mind’ and not be aware of the significance of this loss.

It’s hard not to see Patience Hodgson crowd-surfing during ‘Fight for Your Right (To Party)’ and not understand the impact of The Zoo on Brisbane’s music consciousness.

But it’s not hard to scream along with the lyrics – feeling like, in this place, you and everyone else are part of something extraordinary.

What’s next?

So now that the middle rung is gone, what does that mean for smaller bands in Brisbane?

According to Ms Hodgson, it’s not really up to them.

“I think we’ve had a council that has pretended to care about the Brisbane music scene for a really long time, and they haven’t, and they know they don’t need to,” she said.

“They’ll put money into Bigsound because that sort of seems sexy and international, and that’s how they can pretend to all of us that they’re supporting the Brisbane music scene.

“But I really don’t think there’s enough of it, and I’d just like to see somebody get in Brisbane City Council and make it much better for the arts and for musicians.

“Buy The Zoo and make it a thing!”

Saying goodbye to The Zoo has been hard for Ms Curran – it’s the end of what defined her for many years.

But she’s hopeful music will always return to our lives.

“There’s a lot of people in a lot of pain,” she said.

“If you can’t pay your rent, you can’t go out and see bands. The first thing that goes is entertainment and music.

“But I always say ‘well, I don’t think that we could live in a world that silent’. So we have to try to change it in some ways, because music is in every facet of everybody’s life.

“In the car it’s on, it’s when they have a birthday, it’s when they’re born, it’s when they die. Every single moment is shrouded in music. So if you don’t support it, how does it flourish?”

Meanwhile, we can hold onto the beautiful lightning-in-a-bottle farewell, an event which so faithfully recreated and represented the magic of The Zoo over the years: its love for the industry, its eagerness to advance budding music, and its deep and abiding sense of community.

The Zoo will be missed.

Ned Hammond was at The Zoo for Zoolove on Friday, June 7.