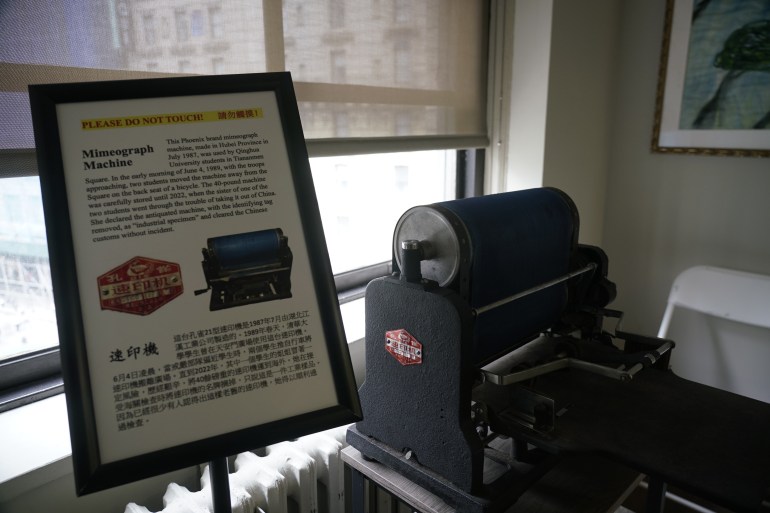

For weeks before that night of bloodshed, Zhou had used the machine, a state-of-the-art photocopier at the time, to churn out leaflets to spread the message of China’s pro-democracy movement.

As one of the last student leaders to leave the square, Zhou tried to talk fellow demonstrators out of heaving the 40-pound (18kg) hulk of solid metal. This may come in handy someday, they argued, and hauled it away on bicycles.

More than three decades later, Zhou was stunned to see that the bulky relic of the rebellion had been secreted out of China for a new museum in New York.

The June 4th Memorial Museum opened a year ago through concerted efforts by Zhou and a few other veterans of the Tiananmen demonstrations now living in the United States. The urgency for a new museum came after the one in Hong Kong was closed down by the authorities there in 2021.

“We viewed this as the effort to erase the memories,” David Dahai Yu, the museum’s director, told Al Jazeera. “We want people to understand why [Tiananmen] happened and what it means…to tell the story.”

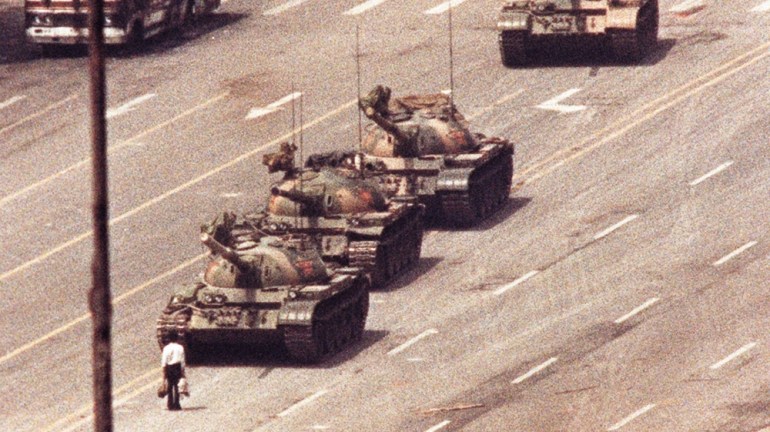

On June 4, 1989, the Chinese government deployed armed troops to crush mass student-led protests that had occupied Tiananmen Square for weeks. At least hundreds of protesters and bystanders, if not more, are believed to have been killed.

In the years afterwards, Hong Kong held an annual mass candlelight vigil for all those who perished, without any interference from Chinese authorities who snubbed out even private memorials in mainland China. And finally, in 2014, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, a coalition initially formed in 1989 to help the mainland protesters, founded the museum.

Times have changed, however. Since 2020, the only city on Chinese soil where the public was free to mark June 4th is now under two draconian national security laws, which ban the annual vigil with threats of arrest and jail time. The Hong Kong museum was shut down just two days before the 32nd anniversary in 2021 and all the exhibits were confiscated.

‘So much that I never knew’

Not all was lost. Instead, as news of the US museum spread, more artefacts from that heady Beijing spring began to appear.

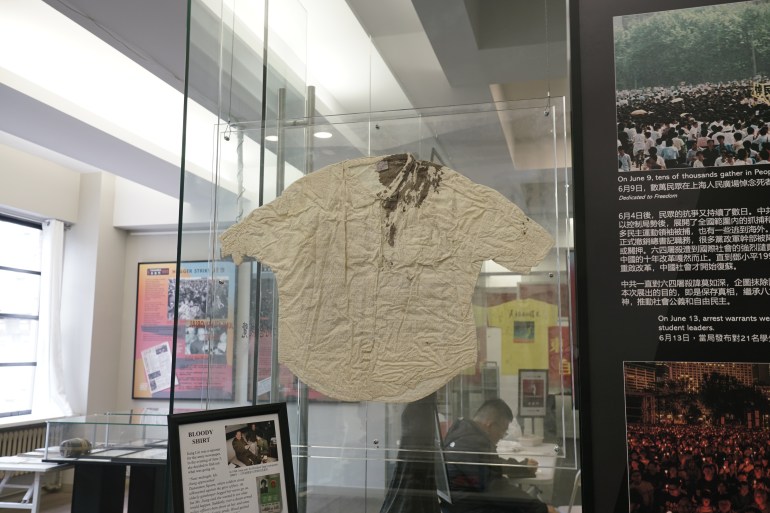

Soon after Zhou and others spread the word on their new museum in the heart of Manhattan’s shopping district, they started receiving unexpected items: the blood-splattered blouse of a reporter who worked for the People’s Liberation Army newspaper; the leaflets distributed by Zhou; a medal and commemorative watch awarded to “the defenders of the motherland”, as Beijing dubbed the soldiers who suppressed the movement.

There was even a like-new Nikko tent, one of the hundreds ferried in from Hong Kong and kept as a memento by a pair of protesters who camped in the square as newlyweds.

Another item bound for the museum was an installation by exiled Chinese artist Chen Weimin, which had been displayed for decades in a California desert.

An avid collector of all things Tiananmen, Zhou told Al Jazeera: “I learned in the process so much that I never knew before.”

Zhou was jailed in China for one year for his involvement in the protests before settling in the US in the early 1990s and founding a humanitarian NGO.

In recent years, he has been helping Hong Kong protesters who fled surveillance and arrest. He asked some of them to fill a room in the museum with an illustrated timeline of the 2019 antigovernment protests. A construction worker’s helmet and a yellow umbrella used by a protester were donated to the museum.

One of the 2019 protesters has parlayed his visual art training and renovation skills into designing the exhibit.

“It’s difficult to explain to outsiders why Hong Kong resorted to violent struggles,” said Locky Mak, 25, who landed in New York last year with only a backpack and requested to be known only by a pseudonym for fear of reprisal. “That said, I feel that [the Tiananmen veterans] admire the Hong Kong people and are very supportive of our struggles.”

For Zhou, the focus of all the remembrances is not just about the tragic end. “It’s also about hope and solidarity: the other possibility for China,” he said.

However, splits emerged soon after Wang Dan, one of the most prominent Tiananmen student leaders and one of the museum’s founders, faced a slew of sexual harassment accusations and related civil lawsuits in Taipei, where he sometimes resides and where he co-founded the New School for Democracy in 2011.

When a group of mainland Chinese students in New York called out Wang in a public statement, they were banned from hosting events at the museum. Yu said he made the decision after they refused to retract their statement, which he called “one-sided”.

Even into its second year of operations, the all-volunteer-run museum has kept limited hours: opening only two days a week for four hours at a time. Fundraising, which kicked off in 2021 soon after the demise of the Hong Kong museum and buoyed by great enthusiasm, has grown sluggish and remains far short of the $2m initial goal. The $580,000 raised so far is sufficient for two more years of operations, according to Yu.

Jiao Ruilin, 31, started volunteering as a museum guide last July 2023, two months after leaving his native Shanghai for freedom in the US. Before, Jiao would learn dribs and drabs about Tiananmen by eavesdropping on whispers among his relatives.

“The exhibits have opened my eyes to the harm of the dictatorship,” Jiao said. “Of course, I want China to change, but I also realise the power of individuals may fall short in affecting change.”

Even so, the Tiananmen veterans are resolved to carry on. Except for a few fake Facebook pages, they said there has been no transnational sabotage from Beijing so far, despite the country’s growing international reach.

Andrew Nathan, a sinologist at New York’s Columbia University who co-edited The Tiananmen Papers, a trove of secret Chinese official documents on the protests and the crackdown, believes the resurrected museum is serving an important role.

“There’s nothing else that keeps the memories alive,” said Nathan.