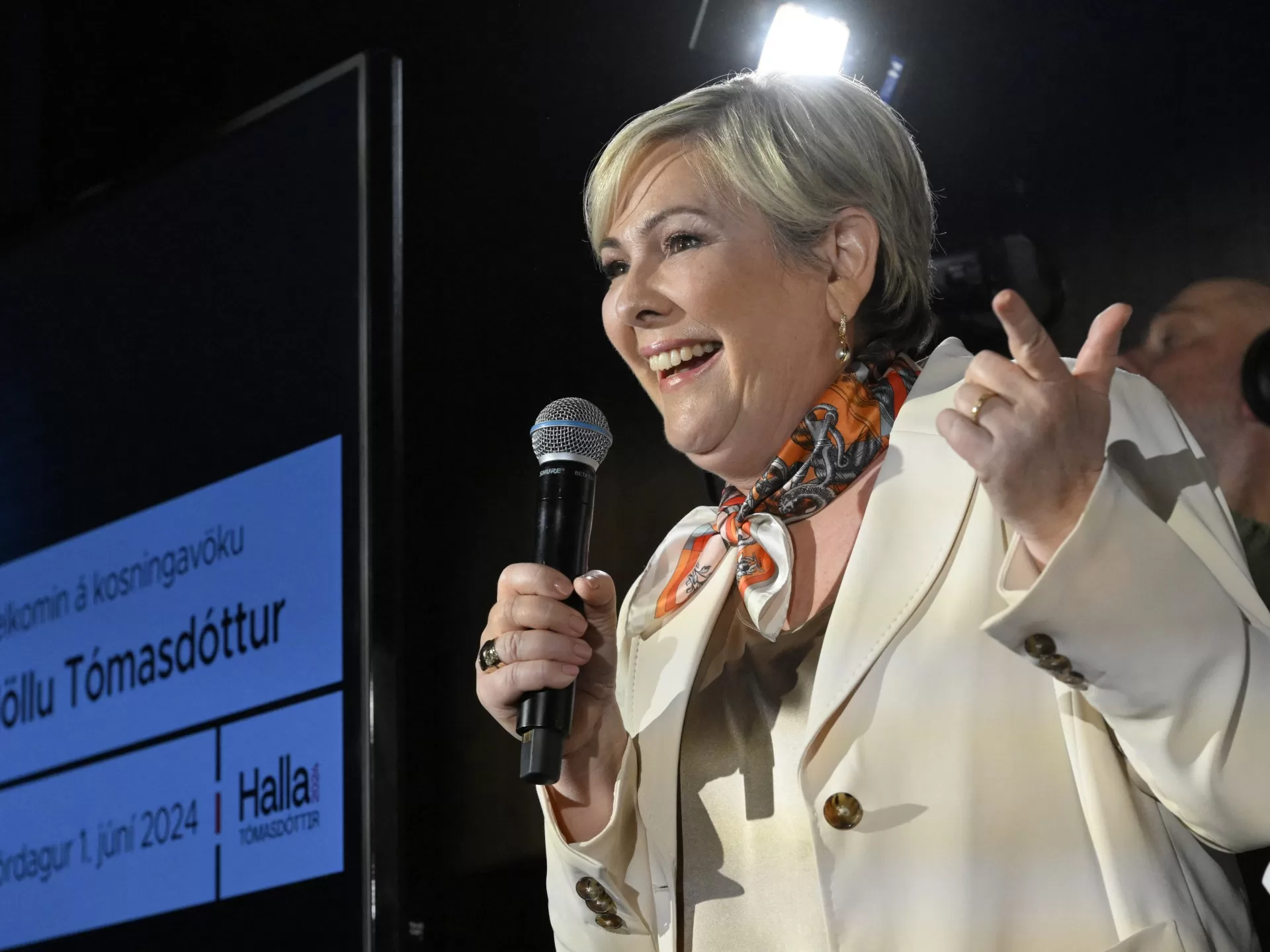

Tomasdottir wins 34.6 percent of the votes to become the Nordic country’s second female president.

Tomasdottir, 55, was elected to the largely ceremonial post with 34.3 percent of the vote, defeating former Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir, with 25.2 percent, and Halla Hrund Logadottir, with 15.5 percent, RUV said on Sunday.

Tomasdottir is currently on leave as chief executive of The B Team, a global nonprofit co-founded by UK business tycoon Richard Branson to promote business practices focused on humanity and the climate, and has offices in New York and London.

Iceland’s president holds a largely ceremonial position in the parliamentary republic, acting as a guarantor of the constitution and national unity. He or she, however, has the power to veto a legislation or submit it to a referendum.

Tomasdottir campaigned as someone who was above party politics and could help open discussions on fundamental issues such as the effect of social media on the mental health of young people, Iceland’s development as a tourist destination and the role of artificial intelligence.

She will replace President Gudni Th Johannesson, who did not seek re-election after two four-year terms. Tomasdottir will take office on August 1.

Iceland’s second woman president

Iceland, a Nordic island nation located in the North Atlantic, has a long tradition of electing women to high office.

Vigdis Finnbogadottir was the first democratically elected female president of any nation when she became Iceland’s head of state in 1980.

The country has also seen two women serve as prime minister in recent years, providing stability during years of political turmoil.

Johanna Sigurdardottir led the government from 2009 to 2013, after the global financial crisis ravaged Iceland’s economy.

Jakobsdottir, 48, became prime minister in 2017, leading a broad coalition that ended the cycle of crises that had triggered three elections in four years. She resigned in April to run for president.

In the country of 380,000 people, any citizen gathering 1,500 signatures can run for office.

While Jakobsdottir was at times seen as the favourite, political observers had suggested that her background as prime minister could weigh against her.

Among the other main candidates in the field of 13 were a political science professor, a comedian, and an Arctic and energy scholar.