Nestled on the outskirts of a central Queensland city, a mammoth network of caves has created the perfect environment to preserve a treasure trove of ancient megafauna that once roamed the region.

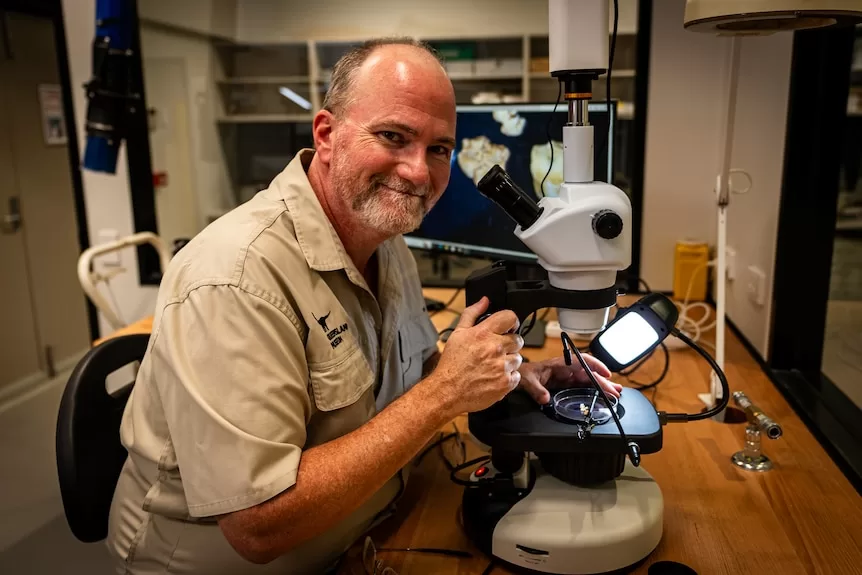

Palaeontologist Scott Hocknull has studied the Capricorn and Mt Etna Caves for the past 30 years.

Dr Hocknull said this fossil deposit was globally unique.

“It’s just sheer luck … the limestone at the caves is 390 million years old … and just happened to be in that right spot at the right time to create caves to collect the animals,” he said.

“If we didn’t have the caves, we would have absolutely no idea that this stuff was going on.”

While it is impossible to travel back in time, 300,000-year-old fossils paint a prehistoric picture of giant koalas, thylacines, tree kangaroos, and even marsupial lions that lived cohesively.

“Looking back into this fossil record gives us an interesting glimpse of a weird and wonderful world that’s extinct,” Dr Hocknull said.

“One in particular, I find probably the cutest of all, is a gigantic ringtail possum that gets to about the size of a bulldog.”

Helping scientists understand climate change

The findings have given scientists key insights into the impact of climate change and how they can protect current species.

“The animals that survived all of that, we have their ancestors as fossils, which show us the way forward, how to help manage and conserve and look after these lineages of animals,” Dr Hocknull said.

Particularly from more recent discoveries of extinct species like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) and thylacoleo (marsupial lion).

“There is the Thylacoleo hilli, which is the little pygmy one, and then there’s the Thylacoleo carnifex that was about the size of a lioness,” Dr Hocknull said.

“And so this is one of the only places in Australia where you find both occurring in the same site.”

Dr Hocknull said only around 5 per cent of the caves had been explored, so their understanding of this ecosystem will continue to evolve.

“There’s always something new, whether it’s a new fossil of the new species, or whether it’s a new fossil from unknown species, but it adds to understanding what these animals look like,” he said.

Now a tourist attraction

The Capricorn Caves’ landscape has evolved over time: from reef to desert and then dense rainforest.

Tourists at The Caves can dig for fossils that are then sent to palaeontologists at the Queensland Museum.

Capricorn Caves operations manager Mindy Bambrick said fossil hunting had become increasingly popular.

“We have this really cool history and story that goes back 390 million years from when it was a reef, but it’s gone through so many other changes as well, which we can tell based on bone records and things that we find in the cave,” Ms Bambrick said.

“It’s the only fossil record of these kinds of species in Australia for this time period. So we find a lot of new species that they’ve never discovered before.”

The booming tourism spot receives more than 400,000 visitors from around the world every year.

“In addition to that, we do school camps, and every term is pretty much full, so there is never a day when we don’t have kids coming or going and doing activities here,” Ms Bambrick said.

The caves were first discovered in the 18th century by Norwegian migrant John Olsen, and have since been privately owned.

The attraction was purchased by a local couple in the 1980s, and it remains one of the biggest privately owned cave systems in Australia.

Get our local newsletter, delivered free each Friday

Posted , updated