Her opponent, Kevin de León, was more than 30 years younger and made Feinstein’s age a central part of his campaign. “Time for a change,” he told voters. Time for “a new voice that expresses the values of California today, not yesterday.”

After winning, Feinstein spent her final years suffering a much-chronicled physical and cognitive decline. She faced incessant calls to quit, which the Democrat studiously ignored, dying hours after a last vote on the Senate floor. She was 90.

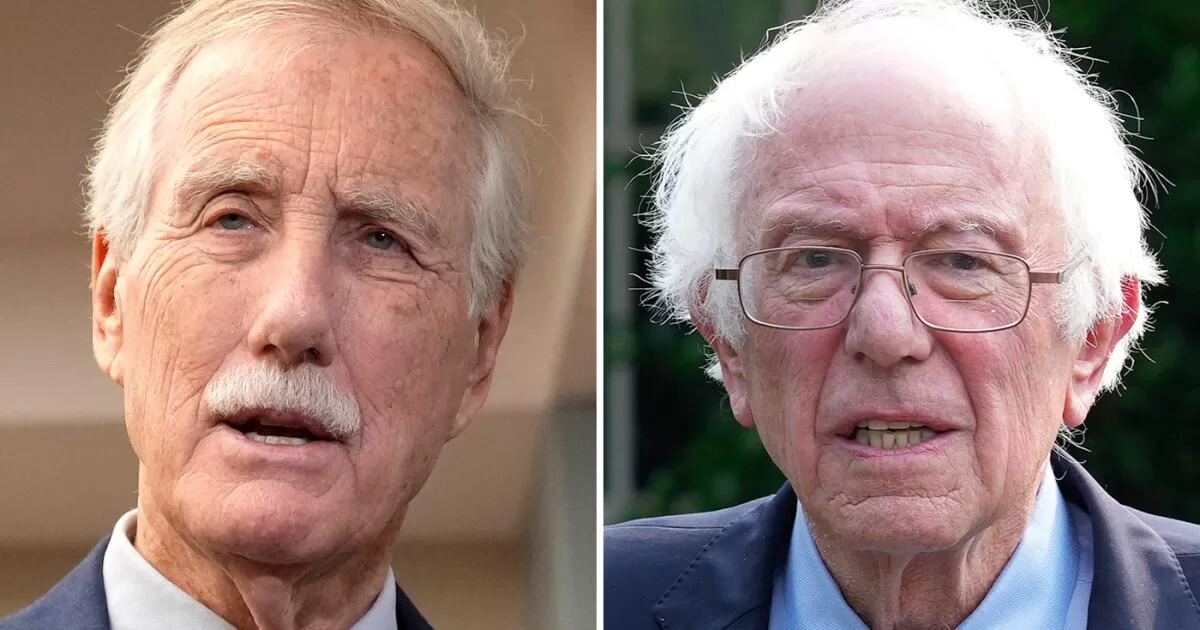

Angus King and Bernie Sanders, two geriatric members of the U.S. Senate, are now up for reelection, seeking their third and fourth terms, respectively. King would be 86 and Sanders 89 in January 2031 when those terms expire.

Both are independents who caucus with Democrats. Each is heavily favored to win in November.

“I’d be stupified if he did not,” Chris Potholm, an emeritus professor at Maine’s Bowdoin College, said of King.

“Unbeatable” was how the University of Vermont’s Garrison Nelson described Sanders. “He’s as solid as can be in the race.”

As the two oldest presidential candidates in history battle for the White House — and President Biden, in particular, faces persistent questions about his mental and physical acuity — it’s striking how little the longevity of the two incumbent senators seems to matter in their reelection bids.

“I have not seen any pushback on Sen. King related to his age,” said Amy Fried, an emerita political science professor at the University of Maine.

The same goes for Sanders, who suffered a heart attack in 2019 during his second run for president.

“I don’t think the age factor is significant enough to threaten his reelection,” said Matthew Dickinson of Vermont’s Middlebury College.

That’s in part because voters typically view political offices through different lenses.

They are “significantly more accepting of an aging person in a legislative position, being one of a hundred in the Senate, or one of 435 in the House, than in an executive post,” said Charlie Cook, who has spent decades handicapping elections nationwide.

“While being a senator or congressman is a more demanding job than many think … it is nothing like being the chief executive.”

That said, was there another standard — a double standard — applied to Feinstein, as an 80-something-going-on-90 woman serving in a body that is still very much a men’s club?

Many of her defenders thought so. Among examples, they pointed to the deference shown Sens. Edward M. Kennedy and John McCain after they were diagnosed with terminal brain cancer. Both stayed in office and were gone from Washington for extended periods receiving medical care. Neither faced the hue and cry that enveloped Feinstein.

The glide paths that King and Sanders are following to reelection would also seem to underscore the notion that Feinstein, their generational peer, was treated more harshly based on her gender.

But there are important distinctions.

Not least, there is no evidence that either King or Sanders suffer the obvious impairments that plagued Feinstein during her final years in office, which were marked by several prolonged absences owing to health issues.

King “has a wicked hard schedule,” said Potholm, who has written a half dozen books on Maine politics. “Talk to him for five minutes and you’ll see he’s sharp as a tack.”

Sanders “shows no slippage, no discernible stuttering or muttering or age-related disconnect,” said Nelson, who has known the senator for more than half a century, going back to Sanders’ rabble-rousing days as a repeatedly unsuccessful candidate for statewide office.

Size also matters.

Maine, with 1.4 million residents, and Vermont, with 650,000, are small states, in both size and population. That makes it easy for voters to get to know politicians on a personal level, forging a connection that’s not possible in California, where politics tend to be more transactional — as in, what have you done for me lately?

Much of the agita surrounding Feinstein stemmed from her stance on policy, particularly from those on the left who long considered the former San Francisco mayor too moderate for their taste. They sought to pressure her into quitting so Gov. Gavin Newsom could appoint someone more reliably liberal.

As Feinstein’s health teetered, the stakes were heightened by the Senate’s near-even split.

She chaired the Judiciary Committee until concerns about her fitness forced her to relinquish the post two years after reelection. She stayed on the committee, but her absences jeopardized Democrats’ ability to confirm Biden’s judicial nominees.

That, and not Feinstein’s gender, made her age “get a lot more of the spotlight” than it might have under different circumstances, said Michele Swers, a Georgetown professor who has authored two books on women in Congress.

In February 2023, Feinstein had the good sense to announce she would not seek another term, clearing the way for a robust campaign to succeed her. When she died last September, Newsom appointed Laphonza Butler as a caretaker.

At 45 — a youngster, by Senate standards — Butler had this to say about King and Sanders: “Every 80-year-old isn’t the same.”

Moreover, she told Politico, “To judge one person, or five people, or two people based on the number on their birth certificate is probably not the best representation of American freedom.”

But don’t take her word, or anyone else’s. It’s up to voters in Maine and Vermont, who’ll have the final say in November.