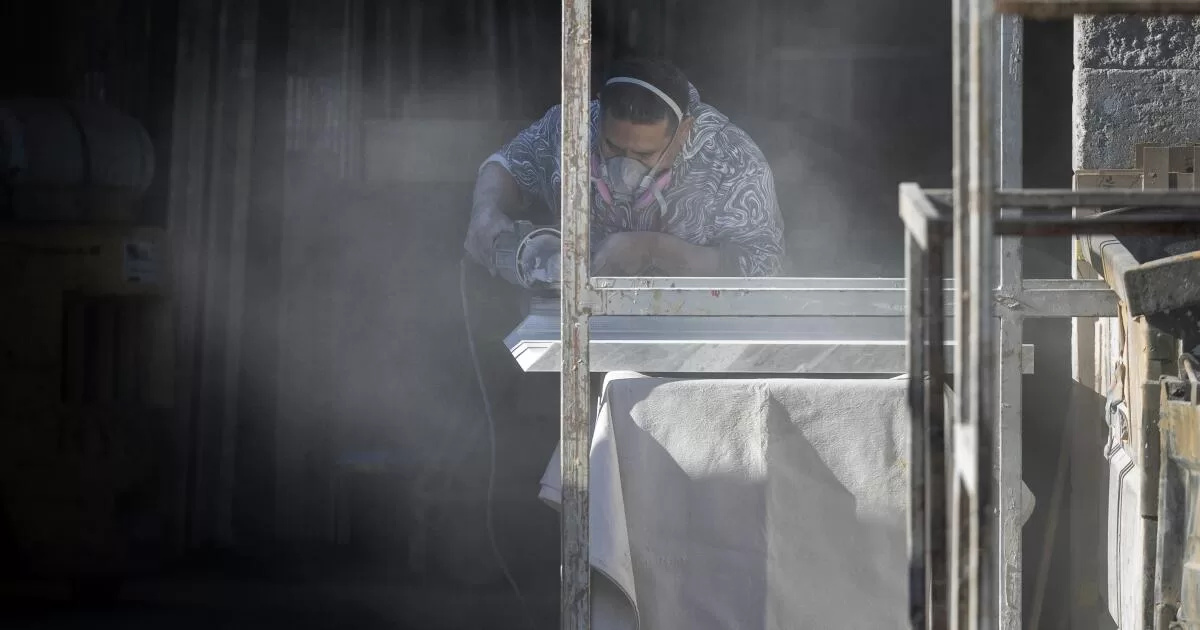

Health officials have tied the rise in silicosis to the surging popularity of engineered stone, an artificial product that can be much higher in silica than natural slabs. The disease is caused by inhaling tiny bits of crystalline silica that scar the lungs, leaving ailing workers reliant on oxygen tanks and lung transplants to survive. More than a dozen countertop workers in California have died, some barely into middle age.

In the San Fernando Valley, outreach workers have found immigrant workers cutting the artificial material in dusty shops with scant protections. When Cal/OSHA took a closer look at the industry in 2019 and 2020, it found that 72% of shops where it conducted air sampling were in violation of silica rules. It recently estimated that out of nearly 5,000 such workers statewide, as many as 200 could die of the disease.

Despite the risks posed by cutting and grinding the material, “there is uncontrolled access in California to materials that contain silica,” said Jim Hieb, chief executive of the Natural Stone Institute, an industry group. “This means anyone can purchase materials and allow any contractor to fabricate them” — cutting and polishing a slab for countertop installation — “without regulatory control.”

That could change if lawmakers pass AB 3043, a state bill that would establish a licensing system for businesses that cut and polish slabs of engineered or natural stone.

Under the bill, no business could legally do stone “fabrication” work in California without such a state license. To obtain one, shops would need to show they were following state requirements for workplace safety and ensure employees were trained in protective measures. The bill would also bar suppliers from providing slabs to unlicensed cutters.

In addition, AB 3043 would prohibit such shops from cutting slabs without using “wet methods” to tamp down dust. Emergency rules adopted in December by state regulators already require such systems whenever risky work is being performed, but Assemblymember Luz Rivas (D-North Hollywood) argued that banning “dry cutting” in state law would strengthen the rule.

Working in this industry should not be “a death sentence,” said Rivas, who introduced the bill.

The state bill would also require Cal/OSHA to start publicly reporting on its website on any orders prohibiting activities at stonecutting shops in the previous year, as well as mandate reports to lawmakers about which parts of the state have the highest numbers of violations and how many licenses have been issued.

The legislation was sponsored by the State Building and Construction Trades Council and is also backed by the American Lung Assn. in California and the Western Occupational & Environmental Medical Assn.

The hope is that as many stonecutting businesses step forward and get licensed, Cal/OSHA “may be able to shine a light on the parts of the industry they know about that haven’t registered” and “target their resources,” said Jeremy Smith, chief of staff for the State Building and Construction Trades Council.

Business groups had bristled at an earlier version of the bill that imposed wage requirements, which were later stripped from the proposal. The Silica Safety Coalition, an industry group that argues silicosis can be prevented with the use of safety measures, said it was now backing the bill. So is the Natural Stone Institute.

“Careful implementation of the licensure program registration, coupled with strict monitoring and enforcement will be critical to the success of this program,” Hieb said in an email.

Enforcement has been a serious question in the face of high vacancy rates at Cal/OSHA. Even knowing how many stone fabrication shops exist has been a challenge for state regulators: At a UCLA conference in May, a California Department of Public Health official estimated there were more than 900 stonecutting shops across the state. In another presentation that same morning, Hieb said his group pegged the figure around 3,000.

Whenever a state bill involves Cal/OSHA, “that is in the back of everybody’s mind. … Are they going to have the wherewithal to really do what we want this bill to do?” Smith said.

Funding could be a problem: Under the bill, any stonecutting shops seeking a license would need to pay fees — $650 in total for an initial application, $450 for a renewal — which would go into a state fund used to enforce the rules. AB 3043 would also require stonecutting businesses to bear the costs of training workers.

But an Assembly Appropriations Committee analysis concluded that fees and possible penalties under the bill were unlikely to cover the costs of the regulatory structure set out by AB 3043, potentially requiring other funding from the state as it grapples with a yawning deficit. Rivas said she and other lawmakers are still assessing the fees needed to support rigorous enforcement.

Among those who have questioned the bill is Assemblymember Diane Dixon (R-Newport Beach), who voted against AB 3043 in committee. In a statement, Dixon said among her concerns was that “the worker training requirements in this bill are largely duplicative of existing training requirements under Cal/OSHA regulations.” Rivas disputed that argument.

Dr. Robert Blink, past president of the Western Occupational & Environmental Medical Assn., argued that the state needs to impose a fee on every square foot of stone slab that is sold, “producing enough money every year to actually fund the necessary training, education, registration, tracking, enforcement and so forth.”

Scofflaw shops will still try to ignore the rules if AB 3043 passes, he said. “If there is enough energy addressed to reining them in … then it will help a lot,” Blink said.

Rivas said that she would have tried to ban engineered stone — a decision soon to go into effect in Australia — if she thought such a bill would have a chance at passing. In Australia, workplace safety regulators concluded that “the only way to ensure that another generation of Australian workers do not contract silicosis from such work is to prohibit its use” entirely.

Short of such a ban, Rivas said, “we’re trying to create a way that workers will be safe.”