She was glad to do so.

“I am really passionate about abortion access,” Heesch said. “It is, especially in Arizona, something that’s being threatened and it shouldn’t be. It needs to be available to everyone and anyone that needs it.”

But her passion fizzled when it came to the presidential race.

The 22-year-old childcare worker, who just graduated from Arizona State University in Tempe, has paid little mind to the contest. And while she definitely won’t back Donald Trump, she’s not at all certain she’ll support Joe Biden, as she did in 2020.

She couldn’t say why. “Maybe he’s not the best candidate?” Heesch ventured, before tepidly pledging a maybe-vote for the president.

“I will if I have to,” she said. “I think.”

As Biden battles for a second term, he’s counting on reluctant voters like Heesch to eventually come around — and ballot measures like the abortion rights initiative in Arizona to help prod them in his direction.

Ever since the Supreme Court overturned Roe vs. Wade, and with it a 50-year-old constitutional right to abortion, the issue has played to Democrats’ considerable advantage.

It helped the party avoid a widely predicted wipeout in the 2022 midterm elections and has also forced Republicans, including Trump, to contort themselves as they try to satisfy social conservatives without alienating the majority of Americans who believe abortion should be legal in most cases.

Voters in seven states — including such GOP strongholds as Kansas, Kentucky and Montana — have either upheld abortion rights at the ballot box or rejected efforts to restrict access.

The issue has yet to be tested, however, in a presidential election year, when turnout will be significantly higher and any number of issues — the economy, border security, the war in Gaza — will compete for voters’ attention.

That doesn’t diminish the importance of the abortion issue. “It’s just a matter of priorities, given all the other ones that matter,” said Republican pollster David Winston.

Nearly a dozen states could have abortion rights initiatives on their ballot in November. (Efforts to place antiabortion measures before voters in Iowa and Pennsylvania fell short.)

Democratic strategists see the issue as vital not just to keeping hold of the White House, but boosting their candidates for Congress and statehouses across the country, in part by engaging voters — in particular Democrats and independents — who might otherwise sit out the election.

“I hear all the arguments about the border and immigration and the economy,” said Mini Tammaraju, president of Reproductive Freedom for All, a national abortion rights organization. “But we can motivate voters on this issue and we can motivate young voters who are, frankly, a little disaffected right now and don’t feel like they’re being listened to.”

Most of the abortion measures that have reached the ballot, or might, are in states such as Maryland, New York and South Dakota that are not seriously contested in the presidential race.

In Florida, voters will decide whether to repeal a six-week abortion ban and codify a right to abortion in the state’s constitution. But Florida is no longer the political battleground it was, having moved decisively toward Republicans in recent years. It is only marginally competitive in November.

That leaves two important swing states, Arizona and Nevada, where Democrats hope abortion rights and measures enshrining them into law will help put Biden over the top.

Both were narrowly decided in 2020, but Arizona was the closer of the two; Biden won by fewer than 11,000 votes, a margin of 0.3%.

The state has since become a focal point of the abortion debate, after its Supreme Court upheld an 1864 law imposing a near-total ban. (Bowing to pressure, the Republican-run Legislature passed a measure defaulting to a 15-week limit, with few exceptions. It was swiftly signed into law by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs.)

The court’s decision “rocked the body politic,” said Stan Barnes, a GOP strategist in Phoenix, and gave a big boost to Democrats up and down the ballot — though he expects the sentiment to dissipate by fall.

Chuck Coughlin, an independent pollster in Phoenix, isn’t so sure.

The abortion issue “unquestionably helps Democrats” as a “motivational thing to turn people out and hang around [Trump’s] neck,” said Coughlin, who used to work for Republicans but left the party after Trump’s election.

“It’s a major tsunami in American political life to take away a right that people have assumed they’ve had,” Coughlin said. “And so the electoral response is, ‘Get your government off my body!’”

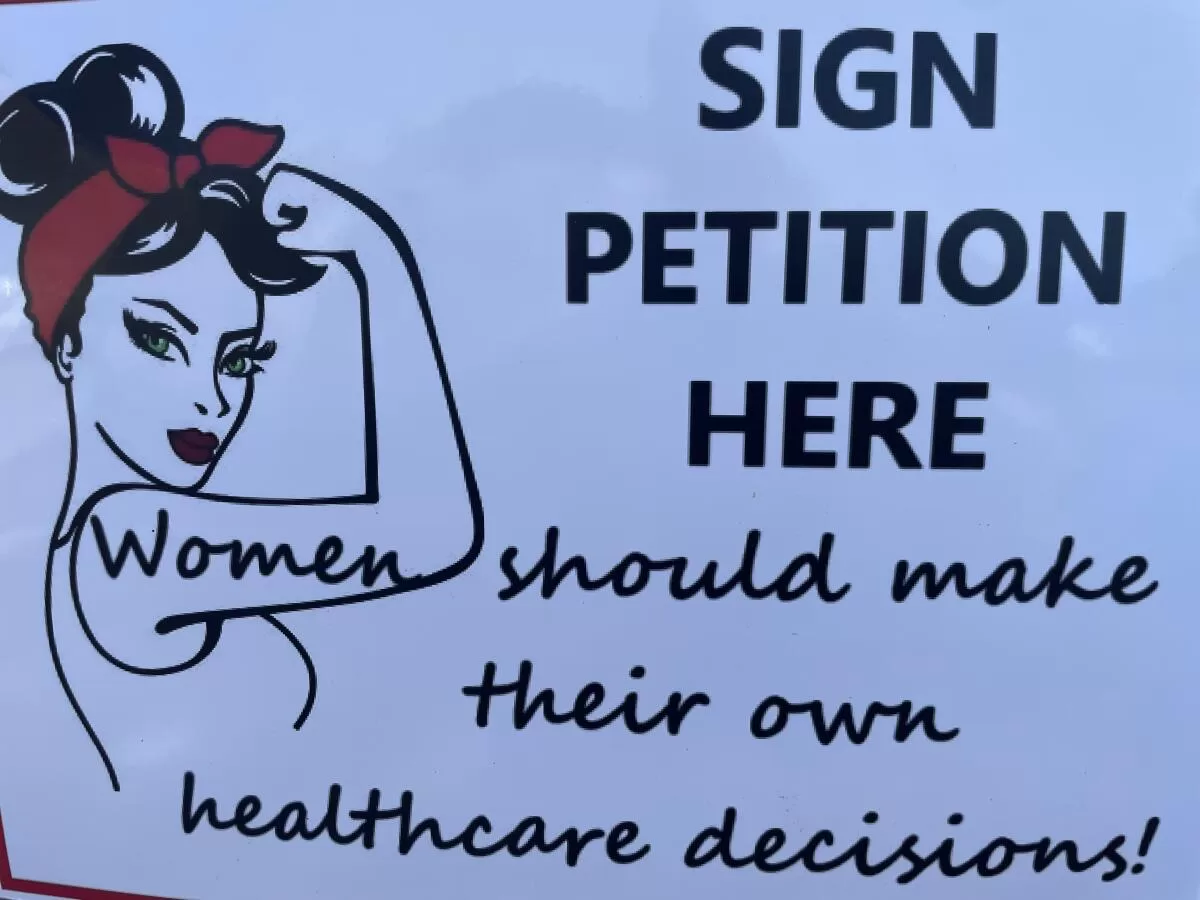

On the far north side of Phoenix, where scraps of desert are still visible amid the relentless urban sprawl, Ruth Lambert was collecting signatures to put the abortion question before voters.

It was already nearing 80 degrees at 8:30 in the morning and Lambert was seated in the corner of a strip mall, sheltered beneath the partial shade of a palo verde tree.

The 73-year-old retiree moved to Arizona in 2004, just as her daughter was about to give birth. That grandchild is now 20, Lambert said, and “can’t wrap her head around” the countrywide rollback of abortion rights.

“It’s almost like a foreign concept,” said Lambert, who has volunteered for the initiative campaign since September.

She’s surprised at how easy it’s been gathering support — organizers expect to turn in the most signatures in state history — and struck by the number of Republicans and self-described conservatives who’ve affixed their names to petitions.

“I really don’t like to talk party. It’s good policy,” Lambert said of the Arizona Right to Abortion initiative, as the measure is formally known. “It’s not necessarily political.”

(Mark Z. Barabak / Los Angeles Times)

But, of course, it very much is. The ballot measure engenders strong resistance from abortion opponents and others who feel it goes too far.

The initiative would amend the state constitution to ensure a “fundamental right” to abortion until fetal viability — or roughly the 24th week of pregnancy — and beyond that if a healthcare professional deemed it necessary to “protect the life or physical or mental health of the pregnant individual.”

Opponents say that would amount to abortion on demand and that is why Coughlin, among others, intends to vote against the initiative — provided it makes the ballot.

That is by no means certain.

After Arizona voters passed a 2016 measure raising the minimum wage, Republican lawmakers pushed through legislation making it much tougher to qualify ballot initiatives, imposing a number of nitpicky rules.

If, for instance, a signature on a petition extends into the one below, both can be disqualified. If someone who is registered to vote as “Jonathan” signs their name “John,” that, too, can be rejected.

And so on.

Organizers say they have already collected well in excess of the roughly 400,000 signatures needed to make the ballot, with more than a month left before the July 3 deadline. The cutoff to start printing ballots is late August.

That opens up “a seven-week gauntlet where every imaginable line on the petition sheets will be challenged,” said Stacy Pearson, a Democratic strategist who has run several initiative campaigns. The final arbiter will the same conservative-leaning Supreme Court that upheld the Civil War-era abortion law.

Polling suggests if the initiative makes the ballot, it will likely pass. And it would probably help Biden and boost the rest of the Democratic ticket at least some.

While abortion may not be top of the mind for most voters, the issue could engage those like Heesch, the 22-year-old childcare worker who otherwise has little use for the president.

“In a lot of ways, Democrats are going to be fighting against the couch” — that is the stay-at-home indifference of voters the party is counting on, said pollster Natalie Jackson.

“In a close election, you’d rather be on the side of the vast majority of the population,” said Jackson, a Democrat who has extensively researched attitudes on abortion. While it won’t be “the top driver” for most, Biden would definitely rather have “the issue at his back.”

It could make all the difference.