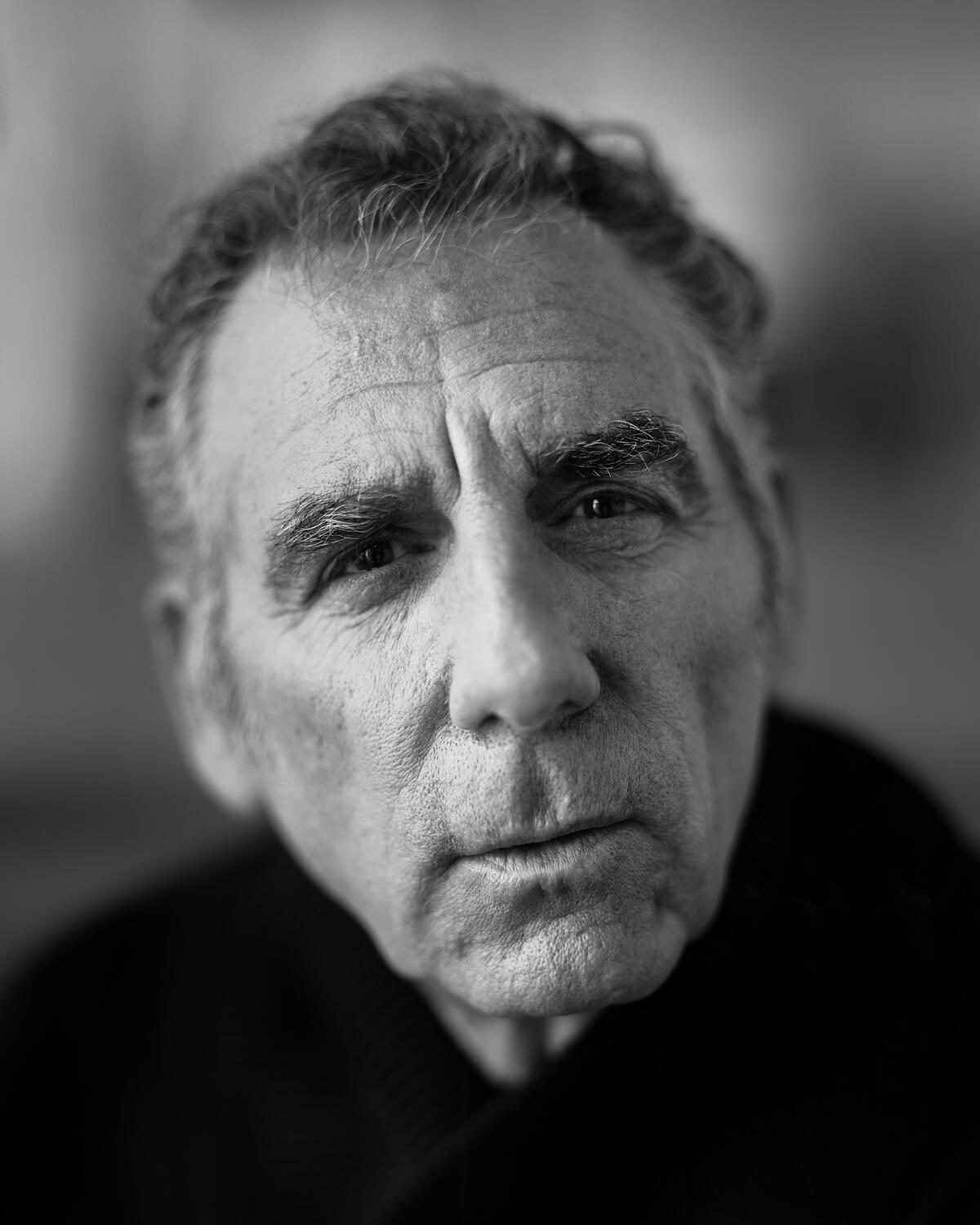

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

On the Shelf

Entrances and Exits

By Michael Richards

Permuted Press: 440 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Michael Richards entered the cultural consciousness, and the apartment next door, as a force of spontaneity named Cosmo Kramer. He was the rubber-limbed, unchained id of “Seinfeld,” the most popular sitcom of its era and a cultural phenomenon cultish in its fervor but too massive to really be considered a cult. Richards and Kramer worked without a net. The energy, the motion, the kavorka forever verged on chaos. But the chaos had a purpose, and it was tremendously popular. Richards won three Emmys for the role, and regularly earned the show’s biggest laughs.

Then, late one November night in 2006, the chaos tipped over into disaster. Performing a surprise set at the Laugh Factory, a venerable Los Angeles comedy club, Richards responded to some hecklers with a viciously ugly tirade. He hurled the N-word about, over and over, turning a night of uncomfortable comedy into the kind of incident that destroys careers. This was early in the era of ubiquitous cellphone cameras, when a horrible mistake could instantly be transmitted around the world. Richards quickly pivoted to damage control, making an appearance via satellite to apologize during his friend Jerry Seinfeld’s visit to “The Late Show With David Letterman.” But the damage was done. He was now widely labeled a racist, and worse.

Richards addresses his night of infamy in his new memoir, “Entrances and Exits,” and once again apologizes. The pop culture mulch machine will quickly reduce the book to soundbites: “Michael Richards says he’s not a racist!” But the Laugh Factory incident is but one tendril of Richards’ book, albeit an important one, tying into the dangerous high-wire act of performance in general and stand-up comedy in particular. It’s the story of a very lonely kid, raised by a working mother, a schizophrenic grandmother and the streets of Southern California; an army veteran who found his life’s purpose on the stage, poured everything into his craft, rose to the height of his profession, never learned to control his rage, flamed out in horrific fashion — and set about slowly rebuilding himself.

It’s also a reminder that everyone is more than the worst thing that ever happened to them — and that stability and comedy don’t always get along.

“It’s what I call the irrational,” Richards, 74, said in a telephone interview from his L.A. home. “We’re constantly being challenged … and anger’s in the midst of it. So it’s always an ongoing endeavor with me. We strive to be persistently rational, but there’s always the irrational, there’s always the mistake, there’s always the pratfall.”

“Public condemnation and humiliation are forms of justice,” Michael Richards writes in his memoir about the response to his racist Laugh Factory rant.

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

Before Kramer, before public shame, there was a child wandering around Baldwin Hills, wondering who his father was and what might have happened to him. The kid soon discovered he liked to perform in drama class. It gave him a way to release the confusion and anxiety inside, and to make people laugh. But the kid still had a restless spirit. He studied acting at the California Institute of the Arts, created an absurdist, highly physical comedy act with his friend Ed Begley Jr. and was drafted into the army in 1970. Stationed in West Germany, he joined the V Corps Training Road Show; he took on the role of a colonel for that theater company. He stayed in character 24/7, even obtaining fake official military identification. It was the start of a lifelong obsession with creating and inhabiting a persona.

By 1989, when fellow former “Fridays” writer-cast member Larry David and Seinfeld had him audition for a new series then called “The Seinfeld Chronicles,” Richards was ready to launch. Much of his character, who was originally called Kessler, was on the page. But Richards built him into a rollicking, three-dimensional creation, right down to the clothes on his back.

“What Kramer wore was all hand-picked by me,” Richards said. “I gathered that wardrobe by combing every secondhand store in Southern California looking for shirt packs. All the clothing is out of the ’60s because my character is still pretty much wearing what he wore then. That’s why the pants are short and so forth, because he’s just a little taller. Everything about the character is justified.”

In “Entrances and Exits” Richards writes that he always considered himself more of a character actor or performance artist than a comedian, though he was also a creature of the comedy clubs on and off throughout his career. His act was never scripted and usually wild — falling on tables, walking onto the stage, futzing with the microphone stand and leaving. More than once in the book Richards uses the word “knockabout” to describe his school of comedy. But he also could be quite disciplined: Between seasons of “Seinfeld” he was often off studying acting in New York, trying to hone his craft.

Onstage, Richards generally went where the spirit moved him. And the spirit could get dark and unpredictable. He was friends with Sam Kinison, a comic whose entire act was based in rage, and there were times when Kinison alarmed Richards with the diamond-like purity of his anger. “He scares me,” Richards writes of his early impressions of Kinison. “I think he’s crazy and I’m heading in the same direction.”

By 2006 “Seinfeld” was in the rearview mirror. Richards’ follow-up series, “The Michael Richards Show,” had been swiftly canceled in 2000. He was a little adrift, and dipping his toe back into stand-up. On Nov. 17, 2006, he took the stage at the Laugh Factory later than usual. He was ill at ease, in angry-comedian mode, walking that razor’s edge between volatile performer and unhappy human. Then he heard the voice from the balcony: “We don’t think you’re very funny!”

“Of course, looking back at it, I wish I had just agreed with him,” Richards writes. “‘Okay, I’m not very funny tonight. Is there anything I can do? Wash your car, mow your lawn? I don’t want you leaving dissatisfied.’ Instead, I take his remark pretty hard. A solid punch below the belt.”

And he snapped — loudly, violently, using some of the ugliest language known to man.

Yes, he is sorry. And he accepts the descent into purgatory that followed. “Public condemnation and humiliation are forms of justice,” he writes. And nothing about his personal rehabilitation seems merely performative. Richards has spent his post-Laugh Factory years learning to live with himself away from the stage (although he still welcomes the occasional acting gig). He has studied the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta in Cambodia. He and his second wife, Beth, had a son, with whom he has finally brought himself to enjoy watching “Seinfeld” (for many years he was haunted by thoughts of how much better his performance could have been). He has fought, and, for the time being, defeated prostate cancer.

Michael Richards says these days, “I sit with the natural world, which seems to be behind most of everything we’re up to.” His memoir, “Entrances and Exits,” is out June 4.

(Marcus Ubungen / For The Times)

He is intent to continue doing what he calls “heart work,” figuring out who he really is and what animates the darkness within. Much like the kid who once roamed Baldwin Hills, he takes daily walks in the mountains of Southern California. “I want to get behind the behind, behind the words, the anger, the person, the cultural conditions and so forth,” he said. “So I sit with the natural world, which seems to be behind most of everything we’re up to.”

Pleas for forgiveness can get boring. “Entrances and Exits” is something else: an accounting of a life and the performances that go into it, for better and worse.