Minister announces compensation plans a day after a report found civil servants and doctors exposed patients to unacceptable risks.

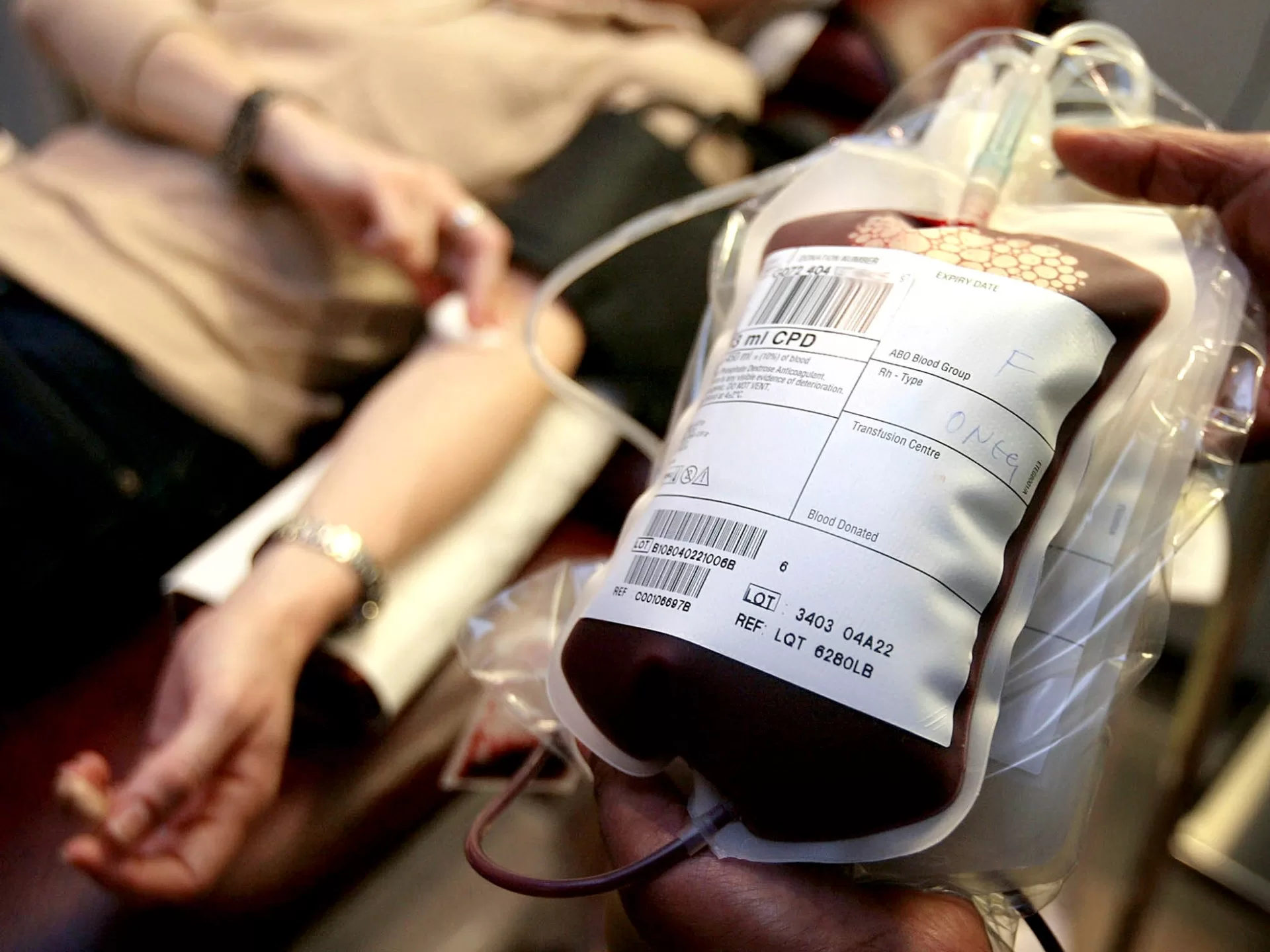

Officials announced the compensation plans on Tuesday, a day after the publication of a report that found civil servants and doctors exposed patients to unacceptable risks by giving them blood transfusions or blood products tainted with HIV or hepatitis from the 1970s to the early 1990s.

The scandal is seen as the deadliest disaster in the history of the United Kingdom’s state-run National Health Service since its inception in 1948.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak on Monday apologised for the “decades-long moral failure at the heart of our national life”.

The report said successive UK governments refused to admit wrongdoing and tried to cover up the scandal, in which an estimated 3,000 people died after receiving the contaminated blood or blood products. In total, the report said about 30,000 people were infected with HIV or hepatitis C, a kind of liver infection, over the period.

Cabinet Office Minister John Glen told lawmakers on Tuesday that he recognised that “time is of the essence,” and that victims who need payments most urgently will receive a further interim compensation of 210,000 pounds ($267,000) within 90 days, in advance of the establishment of the full payment plan.

He also said that friends and family who have cared for those infected would also be eligible to claim compensation.

Authorities made a first interim payment of 100,000 pounds in 2022 to each survivor and bereaved partner. Glen did not confirm the total cost of the compensation package, though it is reported to be more than 10 billion pounds ($12.7bn).

Des Collins, a lawyer representing dozens of the victims, said many bereaved families have not received any payments to date and have no information on how to claim interim payments pledged to the estates of those who have died.

Campaigners have fought for decades to bring official failings to light and secure government compensation. The inquiry was finally approved in 2017, and over the past four years, it reviewed evidence from more than 5,000 witnesses and more than 100,000 documents.

Many of those affected were people with haemophilia, a condition affecting the blood’s ability to clot. In the 1970s, patients were given a new treatment from the United States that contained plasma from high-risk donors, including prison inmates, who were paid to give blood.

Because manufacturers of the treatment mixed plasma from thousands of donations, one infected donor would compromise the whole batch.

The report said approximately 1,250 people with bleeding disorders, including 380 children, were infected with HIV-tainted blood products.

Three-quarters of them have died. Up to 5,000 others who received the blood products developed chronic hepatitis C.

An estimated 26,800 others were also infected with hepatitis C after receiving blood transfusions, often given in hospitals after childbirth, surgery or an accident, the report said.

The disaster could have largely been avoided had officials taken steps to address the known risks linked to blood transfusions or the use of blood products, the report concluded, adding that the UK lagged behind many developed countries in introducing rigorous screening of blood products and blood donor selection.

The harm done was worsened by concealment and a defensive culture within the government and health services, the inquiry found.