The resolution was proposed by Germany and Rwanda and is supported by a significant number of UN member states. Besides designating a day of commemoration, the resolution also condemns “without reservation any denial of the Srebrenica Genocide as a historical event”, and urges member states “to preserve the facts, including through their educational systems, by developing appropriate programmes”, and undertake action to prevent “denial and distortion, and occurrence of genocides in the future”.

It also emphasises the importance of “completing the process of finding and identifying the remaining victims of the Srebrenica Genocide and according them a dignified burial”, and calls for “the continued prosecution of those perpetrators of the Srebrenica Genocide who have yet to face justice”.

As a survivor of the genocide, I consider this resolution a much-needed acknowledgement of what happened, and the proposed day of remembrance – a crucial act of preserving the memory of the fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, sons, daughters, grandparents, and other people we loved, who were violently and cruelly taken away from us.

As their existence and our suffering are constantly denied, and their torturers and murderers are celebrated, this resolution gives hope that their remains will be found and that those responsible for our suffering will be brought to justice. This is crucial for the reconciliation and healing processes, and it is a necessary step for the prevention of future genocides.

My family is one of thousands who are still searching for the remains of our loved ones, killed by Bosnian Serb forces in the genocide.

In the summer of 1992, when the mass killings and disappearances of Bosniak Muslims intensified in my hometown of Višegrad, my mother and father decided to split the family. Bosnian Serb forces were targeting and killing Bosniak men and boys first and kidnapping women and girls who would be raped and murdered.

So my father took my 17-year-old brother and they fled Višegrad. My 13-year-old sister joined my aunt’s family who also left. They all temporarily settled in Crni Vrh – a village between Višegrad and Goražde, which was not yet captured by the Serb forces.

My mother and I – just six years old then – went to her parents’ village. In rushing to flee, we had to leave behind my paternal grandmother, who was unable to walk due to her severe asthma. Her remains were uncovered 18 years later in the Perućac lake mass grave.

In my mother’s village, we were still not safe. As we made preparations to flee again, my mother tried to convince me to leave behind my baby doll. Realising how hard it was for me to give up the doll, my grandfather hid it with other family valuables so “I could find it when we return”. We never returned, and I never saw my grandfather again.

He and the other men from the village fled to Srebrenica. A few weeks later, my mother, grandmother, and I managed to escape to Crni Vrh.

We reunited with my brother, father and sister for a short period of time in Crni Vrh. Just a few days later, my father was ambushed while doing reconnaissance with a couple of other men and went missing. We never found out what had happened to him. Soon after we had to flee again and we managed to reach Goražde, a town in southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, declared as one of the safe areas by the United Nations in 1993.

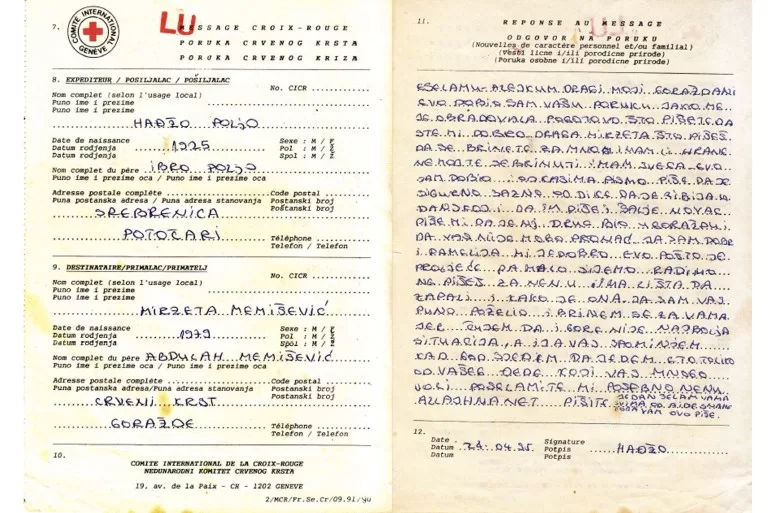

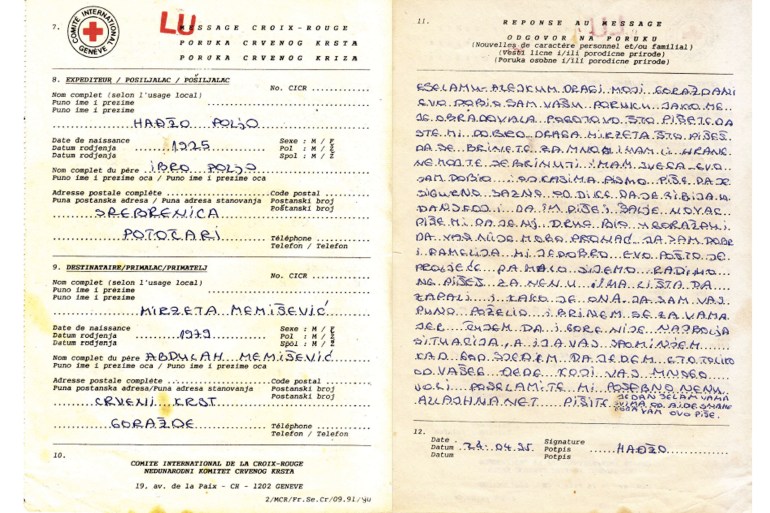

We spent the next three and a half years, marked by death, fear and uncertainty, in the refugee centre there. We communicated with my grandfather in Srebrenica through letters the Red Cross delivered. In one of his last letters to us, dated April 24, 1995, he reassured us that he had enough food and urged us not to worry about him. He told us that he loved us and worried about us, as he had heard that the situation in Goražde was not good.

In July 1995, he and many other men and boys from his village were killed in the genocide. His partial remains were recovered from a mass grave near Zvornik in 2009. Then, in 2020, one of his missing arm bones was exhumed from another mass grave.

The reason so often only partial remains of victims’ are uncovered is because the Bosnian Serb forces tried to hide evidence of their crimes by digging up mass graves and transferring bodies multiple times. In many cases, ravines, rivers and lakes were used as mass graves.

I will never forget the day we learned about the “fall of Srebrenica” and I witnessed my mother’s pain as she heard about the mass killings. As I grew older, I became aware of how she endured unbearable loss – our father, our home, our town, and everything we had – with dignity and grace. However, it will forever be embedded in my memory how devastated she was when she learned about her father’s death. “Was he afraid? How did they kill him? Was he tortured or humiliated? What was he thinking about in his last minutes?” she asked herself.

Remembering her pain, I spent my childhood and most of my adult life wishing never to find the remains of my father, grandfather, paternal grandmother and other extended family members who were missing, fearing what we could learn about their last days and hours. As a child, I did not understand the survivors’ need to find the bodies of loved ones.

My father’s aunt, whose three sons were killed trying to flee from Zepa in 1995, devoted her life to finding their remains, to “bury them properly”, so she and their souls could finally find peace. She died without finding the remains of two of them.

Her story is similar to that of hundreds of mothers in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Hajra Ćatić, the head of the Women of Srebrenica association, spent her life searching for the remains of her only son, journalist Nihad Ćatić, who famously reported in his last dispatch for Radio Bosnia and Herzegovina on July 10, 1995: “Srebrenica is turning into the biggest slaughterhouse”.

“Finding even one bone would bring me back to life,” Hajra said in 2020, before passing away the following year without ever finding even that single bone of her son’s remains.

As many survivors, including my family, continue to search for the remains of more than 7,500 victims, of which 1,200 were killed in Srebrenica alone, high-ranking state officials in Serbia and Republika Srpska, politicians, journalists, and citizens, continue to deny that the genocide took place. They have called it a “fabricated myth”, questioned the reported number of victims, and accused survivors of making “tombstones in Potočari for living people”, referring to the location of the Srebrenica genocide memorial-cemetery.

In 2018, the Republika Srpska parliament rejected a 2004 report, issued by a special investigative commission established by a previous Republika Srpska government, which acknowledged that Bosnian Serb forces had committed the crime of genocide in 1995.

Then in 2019, the Republika Srpska entity set up a supposedly independent commission – the Independent International Commission for Investigating the Sufferings of all Peoples in the Srebrenica Region in the Period from 1992 to 1995 – to “determine the truth”.

In July 2021, it published its “concluding report”, which claimed that most of those killed in Srebrenica were Bosniak soldiers and not civilians and that what happened was an “horrific consequence” of their refusal to surrender to Serb forces. The document also accused the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICYT) of staging politically biased trials of Bosnian Serb political and military leaders, and of wrongly classifying the Srebrenica massacres as genocide. The report was heavily criticised and rejected by lawyers, genocide scholars, and experts in transitional justice.

Such institutionalised denial and distortion of the truth has led to the continued dehumanisation of the victims and survivors. One poignant recent example is the case of orthopaedic doctor Nebojša Mraović.

On September 21, the incomplete remains of two Srebrenica genocide victims were exhumed from the yard of his home in Brčko District. According to a witness, they had been brought there in 1997 and were subsequently buried under a fountain.

When asked about them, Mraović, who has a private orthopaedic clinic in the city of Brčko, said that he did not see anything wrong in possessing the remains and that he used the bones for “planning operations”. He explained he had found them in the woods while hunting.

The remains found in his yard belonged to Mensur Nukić and Salko Hadžić, victims of the Srebrenica genocide; their other body parts were found in mass graves in Vlasenica in 2000.

Mraović has continued his practice and his licence has not been revoked. His lack of remorse is a reminder of the dehumanisation of the Bosniak Muslims that led to the genocide in the 1990s and represents an increasingly apparent threat of a repeat of these atrocities.

Amid the continuing historical revisionism by Republika Srpska’s authorities and society, it is more urgent than ever to counter genocide denial.

The UN Resolution to designate July 11 as the “International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica” is a good step in the right direction.

Adopting the resolution, which recognises and acknowledges the genocide and condemns its denial and the glorification of war criminals, is the least the world can do to defend the dignity of victims and survivors and commit to preventing future genocides.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.