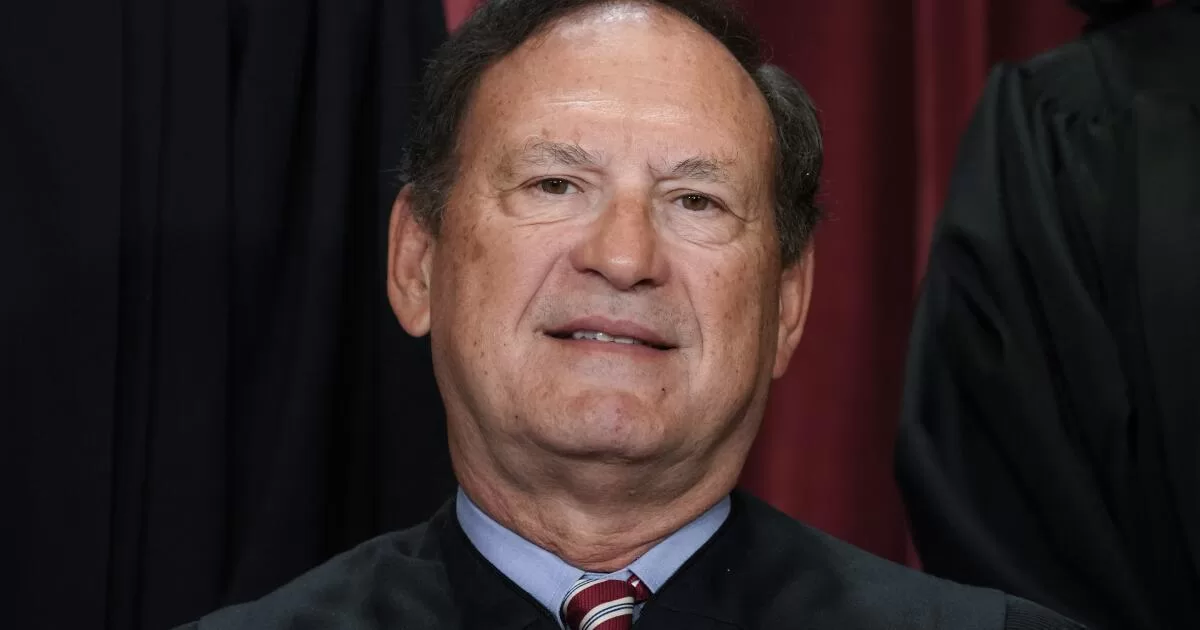

Alito has responded that he is a victim of unjust criticism.

Here’s a look at some of the recent controversies.

What is the upside-down flag incident about?

Last week, the New York Times published a photo showing an American flag flying upside down in front of Alito’s house on Jan. 17, 2021.

Neighbors reported seeing the flag flying for several days after supporters of outgoing President Trump had rioted at the U.S. Capitol.

For some, the upside-down flag became a symbol of the “Stop the Steal” movement.

How did Alito respond to complaints about the flag incident?

He blamed his wife, Martha-Ann, and his neighbors.

“I had no involvement whatsoever in the flying of the flag,” he told the New York Times in an email.

Speaking to a Fox News reporter, he said a neighbor had made vulgar comments to his wife.

Alito suggested it was unfair to criticize him for the upside-down flag because it was his wife’s idea and she had been provoked by neighbors.

He did not explain whether he was troubled by this display of the flag or why he did not insist immediately that it must come down.

Some liberal groups have demanded that Alito recuse himself from proceedings involving Trump. But there is no hint Alito will step aside from deciding the pending case on whether Trump can be prosecuted for “official acts” he took as president.

Are these the first calls for Alito to recuse himself?

No. Last year, Alito gave an interview to the Wall Street Journal complaining about the treatment of Supreme Court justices.

“We’re being hammered daily. And nobody, practically nobody is defending us,” he told two opinion page writers of the Wall Street Journal, which regularly defends Alito and the conservative court. “We are being bombarded. … This type of concerted attack on the court and individual justices” is “new during my lifetime.”

One of the writers, Washington attorney David B. Rivkin, had helped write an appeal petition asking the court to take up a major tax case and rule the Constitution forbids levies on undistributed corporate profits.

Two months later, when the court voted to hear the case, Senate Democrats and progressive groups called for Alito to step aside from ruling on the matter.

The justice fired off a sharp rejoinder. There is “no valid reason for my recusal in this case. When Mr. Rivkin participated in the interviews and co-authored the articles, he did so as a journalist, not an advocate. The case in which he is involved was never mentioned.”

The court is due to issue a decision in that case, Moore vs. United States, in the next few weeks.

How did Alito respond to complaints that some justices failed to disclose free trips?

Alito was upset last summer when he learned ProPublica was about to publish a story on a free fishing trip he took to Alaska in a private jet owned by hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer.

The nonprofit investigative group had earlier revealed that Justice Clarence Thomas had regularly taken free and undisclosed vacations with Texas billionaire Harlan Crow.

Like Thomas, Alito did not mention the luxury trip in 2008 as a gift on the required judicial disclosure report.

When ProPublica sent him several questions about the upcoming story, Alito refused to comment through a court spokeswoman and then sought to debunk the “false charges” in the Journal before the story could appear.

What he described as false charges involved whether he knew or should have known that Singer’s hedge fund was involved in appeals before the high court.

Singer’s hedge fund, NML Capital, had pursued an aggressive strategy of buying Argentina’s bonds at a discount when the country defaulted in 2001 and then fought in the U.S. courts to be paid in full. This 14-year battle between what the Argentines called the “vultures” and Singer’s hedge fund was featured often in the legal and financial press, including the Wall Street Journal.

Singer is a major Republican donor and gave Alito glowing introductions when he spoke to the Federalist Society and the Manhattan Institute.

ProPublica said Singer’s hedge fund was involved in 10 appeals that came before the court. In 2014, the justices agreed to decide a key issue and ruled 7 to 1 in favor of Singer’s hedge fund with Alito in the majority. Singer’s hedge fund was ultimately paid $2.4 billion for its bonds.

Writing in the Journal, Alito said he had no duty to recuse himself from ruling in the case because “I was not aware and had no good reason to be aware that Mr. Singer had an interest” in the cases involving Argentine bonds. When the court agreed to decide the case of “Republic of Argentina vs. NML Capital, Ltd., No. 12-842, Mr. Singer’s name did not appear” in the legal briefs, he said.

Yes, “he introduced me before I gave a speech — as have dozens of other people. … On no occasion have we discussed the activities of his businesses, and we have never talked about any case or issue before the Court,” Alito wrote.