The volunteers say they were inspired by Myanmar’s resistance, which has stood up to one of the most brutal and well-equipped militaries in Southeast Asia since the generals seized power and killed peaceful protesters more than three years ago.

An infantryman in the British army for four years from 2009, with a seven-month tour of Afghanistan, Jason said he returned from eastern Myanmar in late April after eight weeks on the front lines.

Jason – a pseudonym used due to security concerns – said the resistance fighters were “ready to die for the cause” in their all-or-nothing battle against the military.

“It’s different from other places I’ve fought, where you see more fear in the eyes,” he said. “They’re brave people.”

Ethnic armed groups, mainly in the country’s border areas, have been fighting the military for decades, sometimes with the assistance of foreign volunteers.

But since the coup on February 1, 2021, atrocities have spread from the peripheries to the central regions. The military, with a largely Russian-made fleet of fighter jets, has been accused of indiscriminate air strikes against civilians and had burned villages to the ground in what the United Nations and human rights groups have described as possible war crimes.

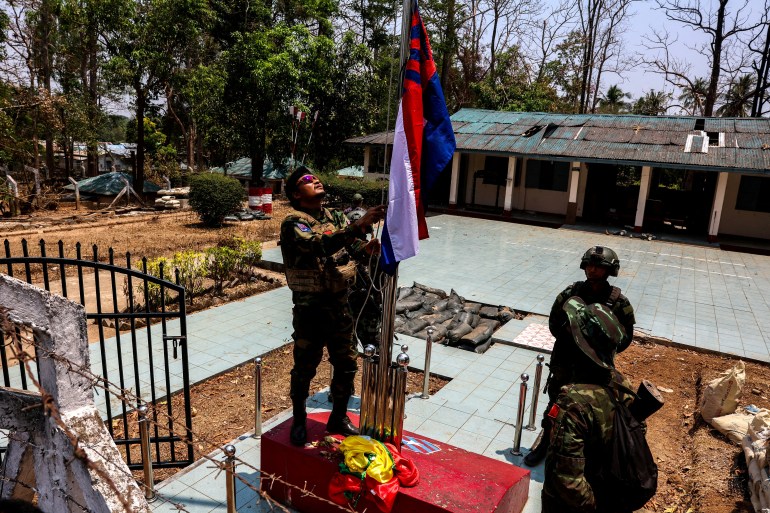

But the generals have been unable to quell the uprising. The resistance has inflicted huge losses and made large territorial gains, initially using slingshots and air rifles against a military wielding a billion-dollar arsenal supplied by Russia and China.

Ethnic armies, public donations and weapon seizures partly as a result of last year’s Operation 1027 offensive have opened the door to better equipment for the resistance, which, even without foreign military assistance, has challenged the military’s staying power.

Myanmar has not experienced the same wave of international volunteers seen in conflicts such as Ukraine or Syria, and there are no coordinated efforts to enlist foreign recruits. Myanmar also has a dizzying number of armed groups scattered across the country.

But foreign fighters, acting in an independent capacity, have travelled to the east and west of Myanmar in clandestine efforts that potentially put them at risk of prosecution in their home countries, and have remained secret until now.

Al Jazeera has seen footage and photos of Jason fighting alongside the resistance in eastern Myanmar. Two sources also witnessed him on the ground.

The British veteran also fought for Ukraine soon after the start of the Russian invasion, spending about a year and a half in the country, he said.

“I’m not a mercenary,” said Jason. “I do it purely for who I think is the right side.”

On seeing untrained and inexperienced foreigners in Ukraine, he does not want the same for Myanmar.

“There’s always the worry that Myanmar could become the next Ukraine with idiots going there,” he said, adding that he joined an unnamed resistance force, which vetted him.

He now has plans to organise a team of six to 10 former servicemen from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Australia and return to help the rebels.

“We have knowledge from four different armies that we can use to teach them,” he said. “My experience there solidified even more my urge to help them. They just want their freedom and democracy.”

He was reluctant to baptise the brewing international unit with a name, which he expects to arrive in Myanmar at an unspecified date later this year.

“We don’t want to be the white saviours, with our own team,” he said. “We would rather work in their system than be our own entity.”

“We’re doing it all for free,” he added. “People have to take time off work.”

‘All one struggle’

On the other side of Myanmar, in mountainous Chin State, which borders India, the People’s Defence Force Zoland (PDF Zoland) resistance group posted a photo on social media on May 11 showing two foreign volunteers: Azad, from the southern US, alongside a British volunteer, who declined to comment.

Azad said he was teaching sniper and infantry courses as well as carrying out reconnaissance and other military duties.

“The junta has retreated to the towns,” he said by phone from Chin State. “The whole countryside has been liberated. Sooner or later, the resistance will start taking the population centres.”

PDF Zoland declined to comment to Al Jazeera.

Azad described himself as a “leftist internationalist” who volunteered for four years with the Kurdish-led YPG (People’s Protection Units) forces in northern Syria.

The 24-year-old said he was involved in political activism while working at a cafe in the US. He has not served in the military, much like his new Gen Z comrades, who are powering Myanmar’s revolution.

He said his rebel commander was “just a couple of years older” than him and “lots of the soldiers were students before”.

Azad sees the fight for autonomy for the Kurds, Arabs, Christians and other minorities in northern Syria as part of a global struggle which includes the Myanmar revolution and Ukraine’s defence against the Russian invasion.

Citing the close ties between the Myanmar regime and Moscow, which analysts say includes a two-way transfer of weapons, Azad said, “It’s all one struggle.”

For him, volunteering in Myanmar was about “a legitimate exchange in solidarity, realising that all our struggles are connected”.

He has been in Chin State for three months and expects more international volunteers to arrive in Myanmar as the revolution shifts from rural guerrilla warfare to urban areas.

“As the rebels gain a stronger position, as the ways in and out of the country slowly become easier, as logistics become better and better, it seems natural there will be more people,” he said.

Although the revolution in Myanmar was “not advocating for socialism in replacing the junta”, he said it was a “new 21st century people’s resistance” that was “hitting on the same notes”.

“Learning about these people, who, in the span of a few short years, went from literally nothing to forming a force that can push the junta back, is really inspiring,” he said. “People here are incredibly brave, putting themselves in situations with ridiculous odds when clearing out bases.”

Outside foreign individuals, the Christian humanitarian group, Free Burma Rangers (FBR), has been well-known since the 1990s for bringing international and local volunteers into ethnic states of eastern Myanmar where minorities have fought back against the military.

Its volunteers provide healthcare and aid to displaced communities and record human rights abuses. It has previously acknowledged that some of its rangers carry weapons for their own protection and to defend the displaced, given the dangerous environment in which they operate.

“We do humanitarian training for all who want it – not military training,” FBR founder and former US special forces soldier David Eubank told Al Jazeera in a text message from Karen State. “We are not a militia nor part of any armed group. We are a frontline relief group.”

Meanwhile, the regime has its own small but powerful foreign support base. It said in April that officials had visited Russia and China to buy combat drones.

Army chief Min Aung Hlaing met Vladimir Putin in Vladivostok last year, while Russian officials have been welcomed as prominent guests at the annual Armed Forces Day parade every March.

Russian military instructors have reportedly flown to the country and trained Myanmar soldiers on Russian-supplied weaponry. Resistance sources in eastern Myanmar say reports sometimes circulate of Russians training regime troops near the front line. Al Jazeera has been unable to confirm the accounts.

A Myanmar resistance commander, who asked for anonymity, said the last report of a Russian trainer was four months ago near his area of operations in Pekon, a town in southern Shan state.

“But we heard he got airlifted as the attacks on the military camps there intensified,” he added.