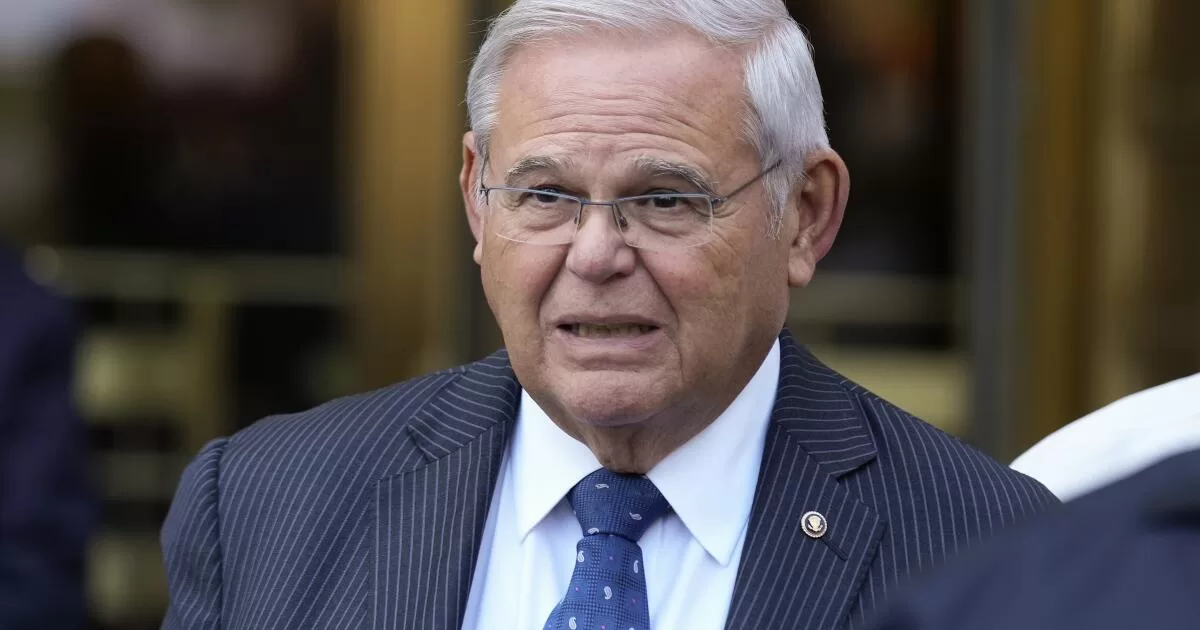

The 70-year-old New Jersey Democrat and his wife are accused of accepting bribes from three wealthy businessmen in his home state and performing a variety of favors in return, including meddling in criminal investigations and taking actions benefiting the governments of Egypt and Qatar.

Menendez’s lawyers say he stayed within the rules and did nothing illegal. He has optimistically spoken about mounting a reelection campaign the summer if he is acquitted.

But even if he escapes without a conviction, as he did in a previous corruption prosecution in 2017, the damage done to his reputation could make a political comeback next to impossible.

FBI agents who searched the senator’s New Jersey home found a stash of gold bars, worth more than $100,000, and more than $486,000 in cash, some of it stuffed into the pockets of clothing hanging in his closets.

His fellow Democrats in Washington, D.C., appear to have already written him off, encouraging him repeatedly to resign.

“The evidence against him is vivid,” said Dan Cassino, executive director of the Fairleigh Dickinson University poll. “This isn’t paperwork or checks: it’s gold bars. The images are powerful, and given that New Jersey voters typically don’t know a lot about the officials representing them, this might be the one thing they know about Menendez.”

Menendez has maintained a defiant stance.

“I am innocent and will prove it no matter how many charges they continue to pile on,” he said after the indictment against him was updated again in early March to add charges that he tried to obstruct the investigation.

Menendez was forced to relinquish his powerful position as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee soon after the revelation last fall of charges including bribery, fraud, extortion and acting as a foreign agent of Egypt.

The senator’s lawyers have suggested in court papers that he will defend himself in part by claiming his wife, Nadine, kept him in the dark about her dealings with the businessmen, who also are charged in the case.

One of them, Jose Uribe, pleaded guilty and is expected to testify. He was accused of buying a Mercedes-Benz for Nadine Menendez after her previous car was destroyed when she struck and killed a man crossing the street. She did not face criminal charges in connection with the fatal crash.

Prosecutors said Sen. Menendez twice tried to help Uribe by trying to influence criminal investigations involving his business associates.

Another man, Wael Hana, is accused of paying off Menendez for helping him get a lucrative deal with the Egyptian government to certify that imported meat met Islamic dietary requirements. Prosecutors said Menendez curried favor with Egyptian officials through acts including ghostwriting a letter to fellow senators encouraging them to lift a hold on $300 million in military aid.

Menendez also pressured a U.S. agriculture official to stop opposing Hana’s company as the sole halal certifier, prosecutors said.

The third businessman, real estate developer Fred Daibes, is accused of delivering gold bars and cash to Menendez and his wife to get the senator to use his clout to help him secure a multimillion-dollar deal with a Qatari investment fund, including by taking actions favorable to Qatar’s government.

Nadine Menendez was charged along with her husband but her trial was postponed until at least July due to a health problem. Her actions, though, will be key to the narrative prosecutors will deliver to jurors through dozens of witnesses during a trial projected to last up to two months.

The three-term senator has held office at every level of government in New Jersey. He got his start in the rough-and-tumble political world of Hudson County, an area across from Manhattan known for influential party bosses.

Menendez was two years out of high school in 1974 when he was elected to Union City’s education board. After stints in the New Jersey state Assembly, state Senate and eventually the U.S. House, he was appointed to the U.S. Senate in 2006, when Jon Corzine resigned to become governor. He won election later that year.

His political career had its first major crisis in 2015 when he was indicted on charges involving a wealthy Florida eye doctor accused of buying Menendez’s influence through luxury vacations and campaign contributions.

At the time, Menendez resolutely denied the charges and vowed not to quit the Senate. A trial ended in 2017 with a deadlocked jury and federal prosecutors in New Jersey abandoned the case.

Menendez not only stayed in Congress, he was reelected and kept his chairmanship of the Foreign Relations Committee. He married Nadine Menendez in 2020 after the couple dated for two years.

Menendez has remained in the Senate after this latest indictment, too, ignoring calls for him to step down before his six-year term ends Jan. 3. Although he has said he won’t run for reelection as a Democrat, he has left open the possibility of an independent run. That could complicate things for Democrats who have a narrow edge in the U.S. Senate and can hardly afford the prospect of a three-way election in the Democratic stronghold of New Jersey.

Unlike in 2015, though, his party largely abandoned him. Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy and others called on him to resign. Democratic Rep. Andy Kim launched a campaign for Menendez’s seat the day after the indictment.

Judge Sidney H. Stein has rejected Menendez’s attempt to claim legislative immunity protects him from the charges.

The judge has yet to rule on whether the defense can call a psychiatrist to show Menendez habitually stored cash in his home as a “fear of scarcity” response to family stories about how their savings were confiscated in the Communist revolution in Cuba, before he was born, and because of financial problems stemming from the gambling problem of his father, a struggling carpenter.

Neumeister and Catalini write for the Associated Press. Catalini reported from Trenton, N.J.