When I saw the burns on Ibrahim Shehu’s right arm, nothing would prepare me for the overwhelming gust of emotions I would feel immediately he turned towards me. I had already spoken with the village head a few minutes after I got to the displacement camp about what happened in Gidan Sale. He spoke of arsons, of men dying, of abductions and eerie emptiness, but the stark reality of the situation would only stare me in the face just as Ibrahim muttered a few more words. My phone fell and tears began to swell in my eyes.

“I was hiding under the bed when they set the room ablaze,” he recalled, stretching his arm so that I could catch the vastness of the pain he went through. I’ve heard about the horrible, horrible things the terrorists perpetrate in rural communities where they hold sway. But there’s a way Ibrahim’s pain seeped into my body and shook me to my core.

Quietly, I pulled aside and allowed my colleague to continue the interview.

I’ve always taken pride in the ability to keep my emotions in check. It’s one way I’ve stayed sane since I started covering the fallouts of the conflict in Nigeria’s North West. The region is suffering from an unimaginably brutal conflict. I have narrowly escaped a terrorist attack in Gidan Ilo, Zamfara. I have been filled with rage watching a young man glowingly talk about the number of innocent men he had extrajudicially killed because they shared lineage with the men terrorising the region. Those were defining moments, yet I got over them quite quickly. But this time, it’s different. This particular harrowing experience will stay with me forever.

This is how it all started.

On the morning of April 17, I learnt that terrorists stormed about five villages along the Marnona-Isa road in the Isa area of Sokoto. They had attacked the villages the previous evening, torched houses, killed locals, and went into the bush with an unspecified number of people. The attack was believed to be a punishment for informing on them. More than 7,000 residents were displaced. Some of them are currently occupying the Mai Tandu Primary School in the main township.

It was just like any other attack, or so I thought. Immediately, I put a call across to my contact (let us call her Hadiza) to brief me on the situation in the area and if it was safe for us to hit the road. Later in the evening, I met with the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and rubbed minds on the raging conflict, especially as displacement numbers and food insecurity keep spiking. We mapped out possible areas of intervention.

I still hadn’t heard from Hadiza, so I texted her again, and we both agreed to move on Saturday the 20th, when some calm might have been restored. My ‘friends’ from DRC shared an update with me, stating that it still wasn’t safe to embark on the journey to Isa. But I wanted to be there so badly.

On Friday Morning, I was just getting up from bed when Hadiza flooded my Whatsapp with texts, suggesting that we shelved the trip till the following week. I understood her fear. The area wasn’t entirely safe. I was just about giving up, too, when she offered to call her brother, who stayed in the main township, to be my guide in case she would not be available to travel with me.

“I just called him. He is out of town. In that case, I will just swallow my fear. Let’s go together,” she finally agreed. I was partly excited and worried, too. But like I used to jokingly say, “We just dey roll dice. Na God dey give double six!”

‘Let’s pray for our safety’

Saturday waltzed in quite quickly. It was morning, around 8 a.m., when I stepped out. The weather forecast for the day was 42 degrees Celsius. It would be hot. For our safety, I wanted us to leave early so we could return that very day.

In this part of the country, everyone has a story to tell. The terrorists ravaging the region do not discriminate with their guns. They have killed infants. Husbands under the glaring watch of their wives. Pregnant women. Livestock are not spared, too. And inside this cab where I was huddled with ten other passengers, everyone shared their stories.

My Hausa is still basic. But Hadiza was beside me, giving me tidbits of the conversations. Except for occasional stops at checkpoints along the Achida-Marnona way, the journey was pretty lively. A few metres away from the military checkpoint at Marnona, just before we turned to the lonely Marnona-Isa road, the driver received a chilly call. Two men had just been killed while trying to deliver ransom to secure the release of one of their wives. I realised we were walking on eggshells.

The road we were approaching was notorious for terrorist attacks. Two years ago, the state government ordered its closure to curtail the menace of terrorists who had made the route their hunting ground. But I understand it’s the quickest route to Isa. The alternative would be driving through Sabon Birnin, which is farther away and also exposed us to the risks.

“Allah ya sa mu dace (let’s pray for our safety),” one passenger suggested.

Everyone grew quiet.

There was a certain uneasiness in the air. It also did not help that there is no telecommunication network. There were fewer and fewer vehicles as we journeyed through the once peaceful road. Villages were deserted. The only thing that signalled that there was once human activity here was the foul stench that greeted us as we approached the villages. The conflict in the region has led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people, opening a floodgate of humanitarian needs with ‘catastrophic’ levels of malnutrition and other related preventable diseases. Yet, it has remained largely ignored.

Finally, we saw a bunch of people by the roadside. They sat on what looked like bed frames. This is Girnashe, Hadiza told me. Several of the villages were raided and set on fire. They were empty. Here, one thing stood out for me; while there were security checkpoints, including roadblocks set by locals, in relatively safer towns, the 90-kilometre stretch of the deadly Marnona-Isa road has no single security checkpoints or presence. I would later learn that the last time it had one was four years ago.

I was already tired and dizzy. We’d left Gidan Sale — one of the worst-hit villages — behind. Two-thirds of the village and vehicles were completely burnt. And not a soul was left there. Everyone had left for neighbouring communities. IOM displacement reports said the attacks affected 5,639 individuals.

Fleeing home for a life of uncertainties

The roaring clanks of the armoured tank and a vehicle on patrol woke me up. We were now in Isa. It seemed like a war front. It’s a warfront, Hadiza corrected me. Soon, we would hail two bike taxis to take us to the head of the town. He was not around. His place was apparently empty, except for a few guards and livestock. We learnt he was in Sokoto town.

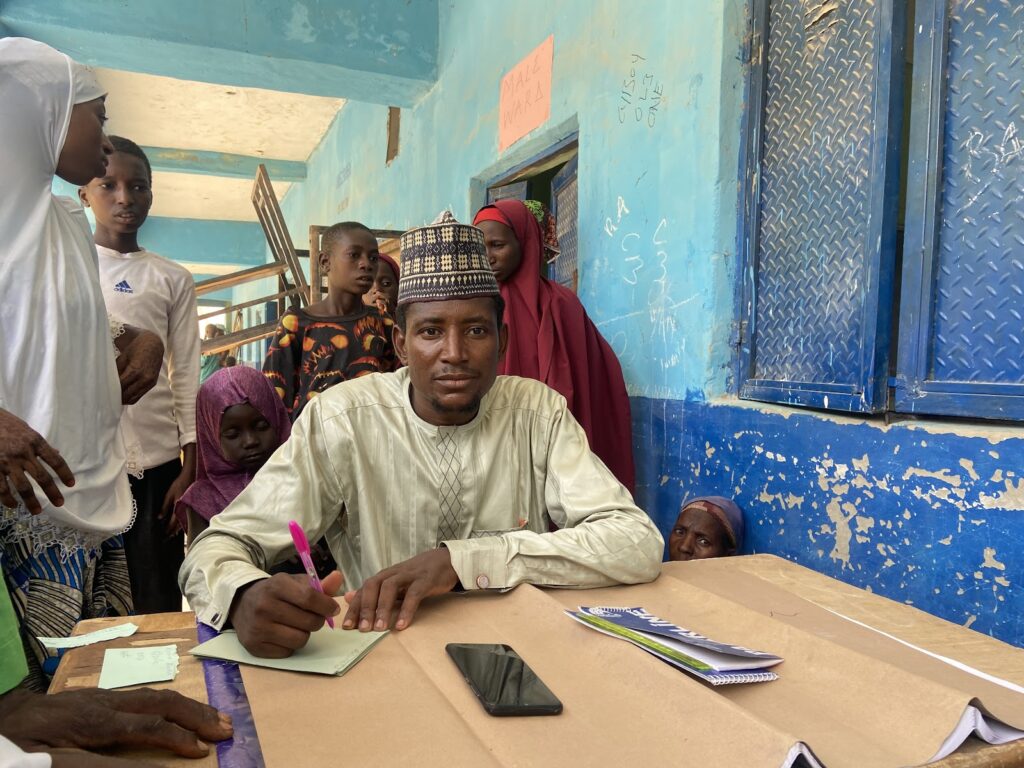

We headed towards the Mai Tandu Model Primary School, where locals displaced from these villages are temporarily staying. About 7,000 of them were in the camp. Across the region, more than 622,000 locals are displaced from their homes. Most of them occupy public facilities or abandoned buildings and struggle to eat and even access healthcare.

A young woman sat to my far right, snacking on uncooked potatoes, with pieces of damp cloth covering her head. She looked exhausted and sad. The previous night, I learnt they had finished five bags of uncooked potatoes, immediately they were supplied by the local authorities. Getting food in camps across the region is an extremely difficult sport.

This was where I saw Ibrahim.

It was 12:45 p.m. Hadiza was conducting the interviews because I had still not gotten a hold of myself. I sat cross-legged on the mat provided for us, still trying to make sense of this level of brutality. Something, however, struck me from where I sat. ‘Camp Clinic’ was boldly written on the wall of one of the newly renovated blocks of classrooms. I was curious to know who was running it.

His name is Abubakar Yusuf. The forty-year-old opened the clinic barely two days after people started arriving at the camp. Abubakar, a community health worker, funded the clinic from his pocket before the local authorities waded in. He would later tell me that the frontline humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) now provides medical aid in the camp.

Abubakar provided statistics about the health needs of residents of the camp. There were 561 under-five children when I visited. A few days later, he told me they lost a 7-month-old baby, who died from excessive smoke inhaled during the time their village was set on fire.

“Most of them came with conjunctivitis. Reddish eyes and discharges. We’ve been able to manage them. There are those with severe burns. And a boy who had a bullet grazed his head. But we’d need more intervention as people are still coming in.”

While walking towards the clinic, my eyes fell upon Hafsah. She’s twenty and has just lost everything she held so dear. Her home. Her husband. Her brother. Her aunt, Amina, was abducted. The two men who had gone to secure her release were also killed. For her, like many others, there’s no home to return to. Almost everyone here has lost something precious to the terrorists.

2:20 p.m. We’ve wrapped up the interviews, so I asked Hadiza to lead us to the motor park. I have a habit of leaving locations I go to for fieldwork immediately. We would later learn that there was no available cab to Sokoto and that it was unsafe to hit the road because it was already late.

We ended up spending the night in Isa.

6:45 a.m. the next morning. We learnt that the villages were now accessible and that some locals were already returning to pick up what remained of their communities. I told Hadiza I’d like to go to the villages and see the extent of the ruins myself. She immediately objected, insisting it was not safe.

A few minutes later, at the park, I raised the same issue. I wanted to go to the villages, even if it was the one closest to the town. The driver stole a look at me as if I wasn’t in my right mind and continued with his conversation. So, I asked Hadiza to speak with him and suggested that he could just wait a split second for me to take a shot. He argued that it was unsafe. I understand. No one would be willing to risk their lives for a shot.

But they did something remarkable. They found a bike man who said he would take me to the nearest village that was attacked. The driver promised to wait for me. I hopped on the bike, and we sped off. The road was unsparingly quiet. I started questioning whether it was safe for us to continue the journey. He assured me we were safe. As we forged ahead, he pointed at relatively smaller settlements that had recently been emptied, too. I noted everything he was saying. By the time we got to Magagindoke-Shinkafi road in Tsabre, he made an abrupt stop. He’d reached the safer part and would no longer move an inch forward. I saw the fear in his eyes and asked that we return to Isa, where I joined Hadiza and departed for Sokoto.

A few days later, I was on my way from Zamfara, where I’d gone to investigate another fallout of the conflict. We were at Gidan Kano, a small village along the Gusau-Sokoto highway, when the driver suddenly made a U-turn. Apparently, terrorists had blocked the road, just before Dambaza. There’s a long line of motorists who had also parked for their safety.

It was not long before the military came to engage the terrorists. I took to my heels when I heard the first gunshots. I didn’t need to know where it was coming from. The first instinct was simply to take cover. Not far off, a small boy laughed at my poor attempt at getting out of harm’s way. Then my colleague, too. It occurred to me in that moment that no one is sane in this part of the country. Not even a journalist covering the human cost of the conflict.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.