While the focus has been on Columbia University in New York and other elite Ivy League institutions, students are also organising for Palestine in the US South. Smaller Southern cities were at the heart of the 1960s civil rights movement, but today, like then, protesters operate in a particularly hostile, even violent environment.

In New Orleans, the largest city in Louisiana, protests have taken place on university campuses and on the city’s streets.

On April 28 for a few hours, the campus encampment movement spilled into the city centre. A few dozen protesters set up green tents in Jackson Square, demanding the city, too, divest from Israel.

This was the first time the encampment movement had spread beyond universities in New Orleans. It signalled a desire on the part of protesters to amplify their message – even before Israel seized control of the Rafah border crossing and intensified its bombing on Monday in preparation for a potentially imminent ground assault on an already devastated area where more than 1.4 million Palestinians, including 600,000 children, are sheltering.

“It’s overdue,” said Kinsey, a supporter of the off-campus encampment who gave only their first name. “It’s been bubbling [up]. The tides were already shifting. That pressure has been building. We’ve used our words. We’ve chanted and marched and been ignored. So now, solidarity encampments are the bare minimum.”

Tackled, handcuffed, Tased

The Jackson Square encampment, which was not claimed by any one organisation, was occupied by a mix of about 40 local artists, builders and service industry workers. Sprawled on the grass, the protesters made demands that echoed that of the student movement: They called for the city to divest from Israeli companies and institutions deemed to be profiting from the war on Gaza. The Port of New Orleans was one institution singled out after it entered into a partnership with Israel’s Port of Ashdod last year.

The protesters sat on the ground at the heart of the city’s French Quarter during one of the city’s busiest tourist weekends when it was hosting its annual Jazz and Heritage Festival. The goal, one protester said, was not necessarily to stay indefinitely – he just hoped police would allow them to stay overnight.

Passing tourists snapped photos. Protesters played music and shared food. About a dozen police officers stood nearby, seemingly unsure about how to force them to dismantle.

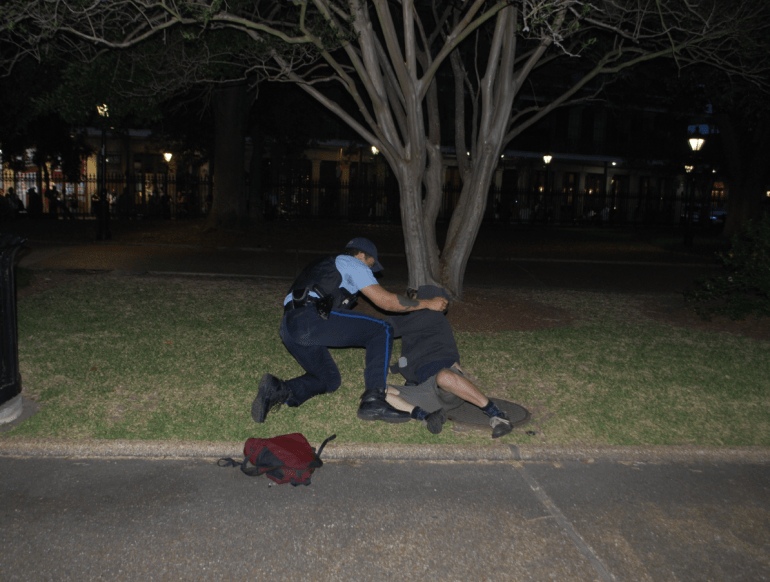

But as night fell a few hours later, things changed. Police announced the park was closed and ordered protesters to leave. When they refused, officers began to grab and then tackle protesters, chasing and arresting 12 people. Three protesters were taken to hospital, two with broken bones. Police used Tasers on several people, at least one of whom was handcuffed on the ground at the time.

One of those arrested appeared in court the next day in a wheelchair due to injuries allegedly inflicted by police and told Al Jazeera that officers broke his leg with a baton. Another suffered a skull fracture, according to a press release issued by some of the protesters.

The charges levelled against those arrested are more severe than what students have typically faced. Two protesters are being charged with a “hate crime against law enforcement”, a charge created in Louisiana in 2016, the equivalent of which exists in just a handful of US states.

Undeterred, a campus encampment sprang up the next day.

A watermelon puppet and 100 state troopers

Students were already planning the encampment at Tulane University, a private university miles across town, before they heard about the off-campus protest in the city centre, they said.

Taking responsibility for protests in Louisiana exposes organisers to great legal risks. A recent court decision means protest organisers can be held liable for the actions of participants. It is also, according to a decades-old state law, illegal to wear masks in public. A pair of bills working their way through the Louisiana State Legislature, 70 percent of whose seats are held by conservative Republicans, would give motorists the right to run over protesters blocking roads if drivers feel they are in danger. Another would make it a crime to be within 25ft (7.6 metres) of a working officer.

Antiwar organisers at Tulane have faced an uphill battle from the start, students said.

“Tulane is one of the most deeply connected institutions to …Israel,” said Kristin Hamilton, a Tulane graduate student. The school leads one of four US-Israel Energy Centers, collaborating with Israeli universities and an Israeli fossil fuel company to research and develop gas extraction.

When students gathered to set up tents on their campus on April 29, police officers, some on horseback, immediately began tearing them down, the students said. Brenna Byrne, a former student at Tulane, said she saw a police horse’s hooves nearly come down on the head of one student who had been detained on the ground. Afraid the student would be killed, she moved forward to help and saw her own sister, Hannah, also on the ground and being arrested, a police officer kneeling on her head. She and five others were arrested.

But suddenly, the police backed off.

Dozens, then hundreds of young people came to the encampment, located between a main thoroughfare and the university president’s office. Students played music, made signs, sang and chanted, “Hold the line for Palestine.” The camp had snacks, a literature table and a 10ft (3-metre) watermelon puppet in a dress – the watermelon having become a widely used symbol for the Palestinian flag. Members of the public came out to drop off supplies.

By the next day, a billboard-sized LED sign had been erected, blasting loud music and displaying a message that warned protesters they were trespassing. Demonstrators as well as a Tulane facilities worker and police present at the site said they believed it was set up by university authorities. The music drowned out attempts by groups of Jewish and Muslim protesters to perform prayers throughout the afternoon.

Despite the threat of dispersal, the mood was upbeat. Silas Gillett, a Jewish sophomore, said: “Multiple people came up to us and said they felt more safe that day than they ever had on campus. Tulane is, usually, a very hostile place for Palestinians, Muslims and students of colour.”

Hamilton recalled people dancing dabke, a traditional Palestinian folk dance, that night, even as police gathered nearby. “To see that Palestinian joy happening at the exact same time the state was trying to oppress and terrorise us – that was really powerful.”

The camp lasted 33 hours.

On May 1 at 3am, more than 100 state troopers in riot gear and backed by armoured vehicles stormed the encampment and arrested 14 students.

“It was overwhelming,” Hamilton recalled. Video footage reviewed by Al Jazeera shows state police pushing Hamilton to the ground, and the student shared medical records showing they were later diagnosed with a concussion as a result of assault. The student believes they were targeted because they were filming the police at the time.

In another video reviewed, an officer pulls a weapon believed to be a bean-bag rifle and aims it point-blank at nearby students.

Students described the police response as “traumatic”.

‘Everything about this one was different’

The police reaction to the Tulane encampment appeared far more organised than the response to the Jackson Square protest: More than 100 state troopers in riot gear moved in one coordinated skirmish line to dismantle the Tulane camp as opposed to the Jackson Square arrests, which were initiated by about a dozen local officers

A lawyer who was acting as a liaison between the Tulane protesters and police said law enforcement “could have de-escalated, but they chose riot gear”. The liaison, who asked not to be identified to prevent retaliation, has acted as a legal observer at dozens of protests over various issues in Louisiana but said, “Everything about this one was different.” The aggression displayed by “the police was like nothing I’ve seen at any protests before”, the liaison added. “It was a militarisation.”

But the reaction towards the demonstrations does not necessarily mean that protesters will not take to the streets in New Orleans again.

Protesters said that while Tulane is hostile towards Palestinians, pro-Palestinian sentiment is still strong in the city. Gillett attributed it in part to New Orleans’s predominantly Black and lower-income population. There is also a significant Palestinian population in the area involved in protesting, and this year, a Palestinian New Orleanian, Tawfic Abdel Jabbar, 17, was killed when he was shot in the head by the Israeli army near Ramallah in the occupied West Bank.

Eman Abdelhadi, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, said that in the US, “brown and Black communities and poorer folks are more supportive of Palestine. And I think the reason is that Palestine is an anti-colonial movement.” Polling has consistently found Black Americans to be more sympathetic to the Palestinian cause than white Americans. “I think we’re seeing that the Palestine movement [is] strongest in places where there’s also a broader, multiracial working class.”

“This is absolutely a class issue,” Hannah Byrne said.

That also means that when authorities turn their power on the protesters, students from racial minorities and lower-income backgrounds often suffer the most.

On April 31, for example, Gillet was notified that he had been suspended from Tulane along with seven other students and evicted from his student housing due to his involvement in the encampment, pending a hearing. He said most of the students he had organised the protests with were on needs-based scholarships. He also has a scholarship, and his suspension may force him to leave school.

The actions of the police and university administration can be viewed as part of a wider climate at Tulane and in Louisiana that has viewed pro-Palestinian sentiment with suspicion and even as a threat. The State Legislature on Wednesday advanced a bill that doubles down on backing for Israel, calling for support for “the nation of Israel in the wake of the October 7, 2023, terror attacks and Israel’s ongoing efforts to root out Hamas”.

Even before the nationwide wave of pro-Palestinian protests, demonstrators were arrested at a Tulane rally in October, and in February, Tulane Professor and former CNN CEO Walter Isaacson was filmed pushing a protesting student.

The majority of Americans under 30 want a permanent ceasefire in Gaza, according to polling data. As Israel presses on with “ironclad” support from the US, what will the Gaza protest movement come to look like?

“I don’t think the protest is starting in university campuses and spilling over,” Abdelhadi said. “I would say the direction has flowed the opposite way,” from the public onto campuses.

Abdelhadi pointed to past civil rights movements where she said there “wasn’t one specific action that changed everything”. Instead, in her view, it was “a combination of all the actions, all the tactics”.

Until Israel’s war in Gaza ends, the anger among pro-Palestinian protesters and their desire for change are unlikely to go away.

“Although we have been suspended, that does not mean we will be giving up,” said Maya Sanchez, another Tulane student involved in the encampment. “As Israel and its violence escalates, so does our commitment to fight for a liberated Palestine.”