It’s a five-minute walk from busy Eagle Rock Boulevard. Even better? Her two-bedroom is $560 per month, thanks to a city law limiting the size of rent increases in older buildings.

But Juarez’s life was upended a few months ago, when she and her family learned their rental and 16 others on Toland Way in Eagle Rock were targeted for demolition to make way for new affordable housing. A proposal for an eight-story, 153-unit building was submitted as part of Executive Directive 1, Mayor Karen Bass’ initiative to fast track the approval of low-cost housing.

The mayor’s initiative, part of her larger fight against homelessness, was created to ensure that 100% affordable housing projects are approved within 60 days, without public hearings. Renters facing displacement from such projects say that timetable leaves them with less time to mobilize — or fight back.

The Eagle Rock development is on hold, with city planners waiting for additional documents. Meanwhile, Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez has begun pushing for new safeguards to ensure that projects submitted under the ED1 program do not result in the rapid demolition of rent-stabilized apartments in her Eastside district.

On Tuesday, the City Council — at Hernandez’s urging — voted 13-0 to instruct the Department of City Planning to draft a temporary ban on the approval of affordable housing projects that result in the demolition of five or more occupied rent-stabilized units in parts of her district.

The moratorium sought by Hernandez would only apply to 100% affordable housing projects — the kind being fast-tracked under ED1 — in portions of Chinatown and Eagle Rock. Hernandez said she selected those areas because they have a high concentration of rent-controlled apartments and are facing major displacement pressure.

“I, as the representative of CD1, have to do everything in my power to try to keep folks housed in my district,” Hernandez told her colleagues. “Because we have a serious eviction-to-homelessness pipeline.”

The new regulations, which must be drafted and come back for another council vote, would buy the city time to develop rules requiring that 100% affordable housing projects provide at least some units for families that are defined as very low-income, said Hernandez spokesperson Chelsea Lucktenberg.

Zach Seidl, a spokesperson for Bass, did not provide the mayor’s position on Hernandez’s proposal when contacted by The Times.

“We are working to protect and support all Angelenos as more housing is built and we bring more Angelenos inside,” Seidl said. “As issues come up, we will take action to address them.”

A developer on Toland Way in Eagle Rock has submitted an application to build a 153-unit affordable housing complex, replacing 17 rent-controlled apartments. Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez is pushing for a moratorium on such projects.

Tuesday’s vote is the latest example of council members looking to rein in real estate developments that would result in the destruction of rent-controlled units. In December, the City Council passed a motion from Councilmember Kevin de León seeking a temporary ban on the demolition of rent-controlled apartments in Boyle Heights.

That ordinance has been drafted but not yet approved by the council, said Pete Brown, a spokesperson for De León. In addition, city agencies are still waiting for feedback from the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development, he said.

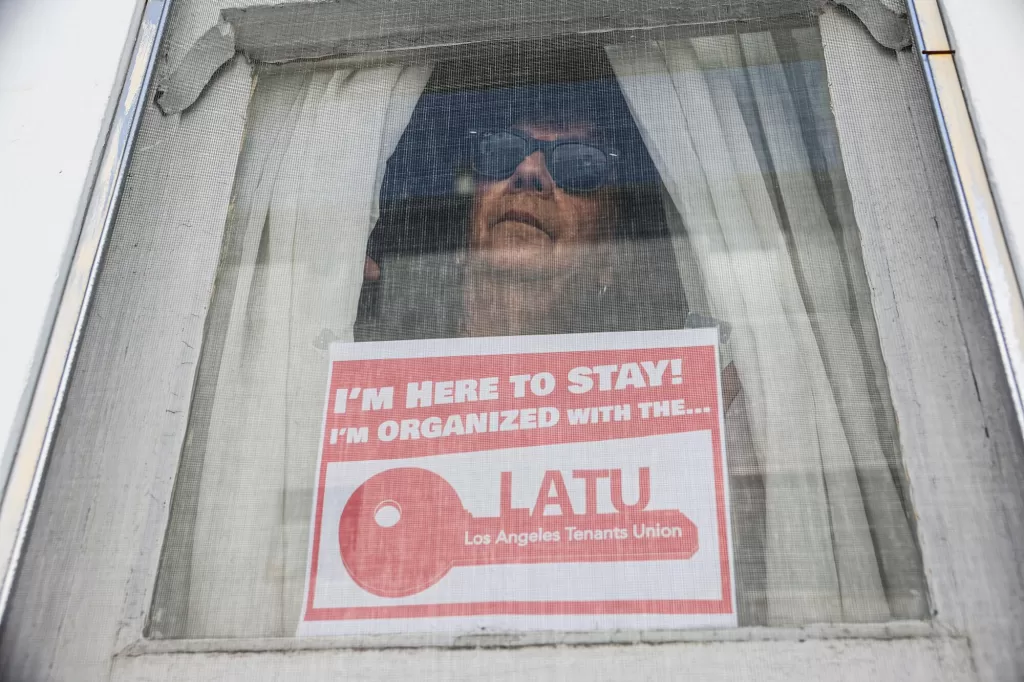

Juarez, who has lived in her home on Toland Way since 1978, said she is grateful to Hernandez for helping her neighborhood with the fight against demolition. She said safeguards aimed at protecting tenants won’t go far enough for her and her neighbors.

According to the city’s housing department, L.A. residents whose rent-controlled apartments are demolished must be provided relocation payments, which can range from $9,900 to $24,650, depending on a renter’s income and other factors.

Juarez, a retired schoolteacher, said she believes she would be eligible for nearly $25,000. But she said rents are now so high that she would likely burn through that money in less than a year.

“There’s no way I can afford to live anywhere in my neighborhood. There’s absolutely no way. Not on my retirement,” said the 71-year-old.

Representatives of JFP Toland LLC, which is listed in city paperwork as the developer of the Toland Way project, did not respond to inquiries or declined comment when contacted by The Times.

Under state law, low-income residents who are displaced to make way for affordable housing also are eligible to move into a comparably priced unit, with the same number of bedrooms, in the replacement building, said Eduardo Mendoza, policy director at the Livable Communities Initiative, a housing and transit advocacy group.

Lucktenberg, the spokesperson for Hernandez, said many tenants cannot realistically take advantage of that opportunity, in part because of the amount of time it takes to build the replacement project. Renters who relocate frequently have to find not just new apartments but also new schools for their children — making it difficult to uproot their families a second time, she said.

Juarez said she’s not interested in moving into the replacement building. And she’s not the only tenant on edge.

Johanna Olivares, 42, said she and her family have been paying $892 per month for their apartment on Toland Way. A 20-year resident of the building, she said the landlord has previously offered cash to her family to move out.

Tenants Johanna Olivares, son Emmanuel Riebeling, 4, and husband, Juan Riebeling, are facing an uncertain future if they are forced out of their rent-controlled apartment.

Appearing at Tuesday’s council meeting, Olivares begged council members to block the new project from being approved.

“I’m a stay-at-home mother. I’m on a fixed income,” she said. “We love Los Angeles.”

A developer is looking to demolish 17 apartments on Toland Way in Eagle Rock, replacing those units with a 153-unit affordable housing complex. The company is looking to take part in Mayor Karen Bass’ Executive Directive 1 program, which fasttracks the approval of such projects.

Bass launched the ED1 initiative in December 2022, during her first week in office. She signed the order to ensure that 100% affordable housing projects would have top priority, not just at the planning department but also at the Department of Building and Safety, which reviews construction work, and the Department of Water and Power, which oversees utility hookups.

The mayor later amended the order to make explicit her intent to prohibit ED1 projects from being approved on properties zoned for single-family homes.

Bass has portrayed the ED1 initiative as a big success, saying it has unleashed a flurry of applications to build affordable housing. During her recent State of the City speech, she announced that the city had cut the permitting process for 100% affordable housing projects from six months to 35 days.

“This has resulted in more than 16,000 additional, new affordable housing units in the pipeline,” she said.

At one point last year, the mayor’s team said that 46 units of new affordable housing were being permitted under ED1 for every rent-controlled unit targeted for demolition.

Still, some renters’ rights activists have been critical. Last year, they pointed out that dozens of tenants in South Los Angeles were being pushed out of apartments targeted for demolition by developers using ED1’s fast-track process.

Johanna Olivares with son Emmanuel Riebeling, 4, and husband, Juan Riebeling, at their home on Toland Way.

Those arguments were repeated during Tuesday’s meeting. Some Toland Way residents fought back tears as they described their fear of being forced out of their apartments. Tenant advocates took direct aim at the mayor.

“I’m here today to ask you to pass this ordinance and defend these families, because the mayor is not going to,” tenant organizer Yaya Castillo told the council. “Let’s speak plainly here: by not protecting our rent-controlled units, Executive Directive 1 has been implemented to accelerate gentrification.”

Bass is looking to transform her executive order into a permanent ordinance. Although the proposal has been endorsed by the city’s planning commission, it has not yet come before the council.