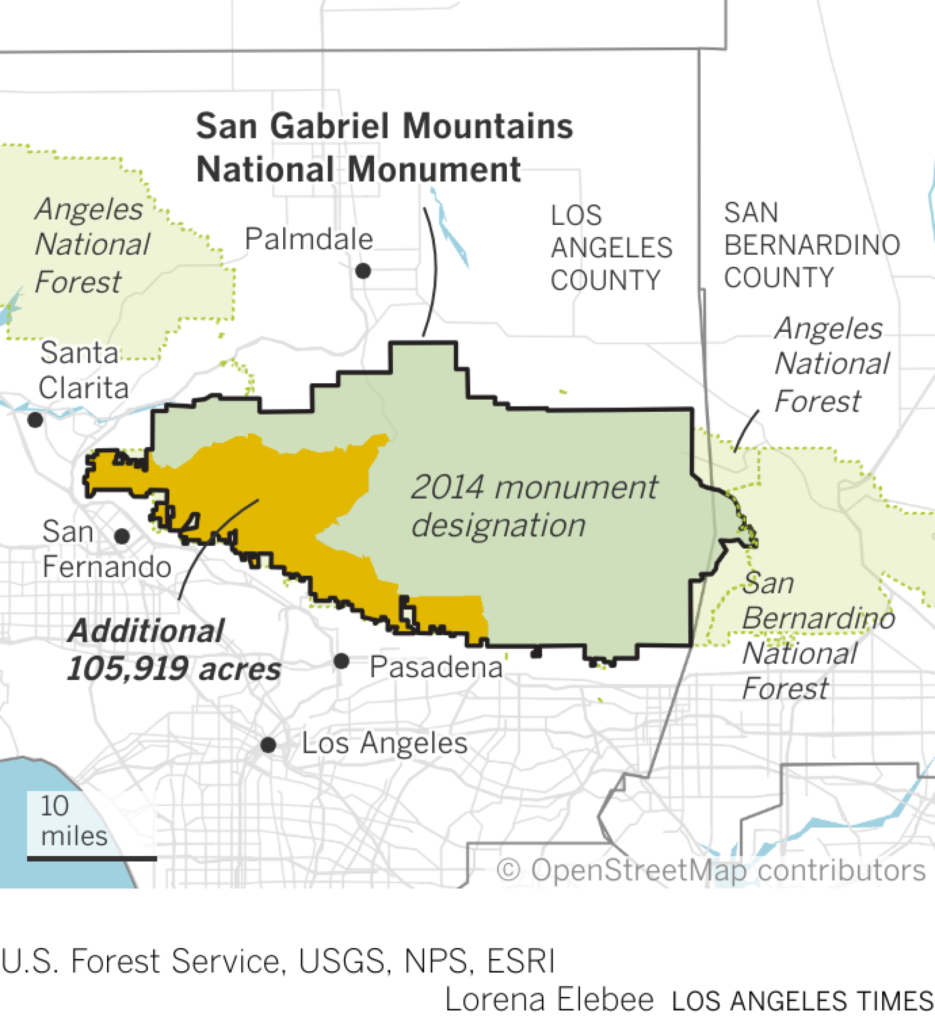

President Biden on Thursday will expand the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument by nearly a third in an action that is being widely praised by the Indigenous leaders, politicians, conservationists and community organizers who had long fought for the enlargement of the protected natural area that serves as the backyard of the Los Angeles Basin.

The president will also sign a proclamation expanding the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument by adding the 13,696-acre Molok Luyuk, or Condor Ridge, to the 330,000-acre swath of rolling oak woodlands, lush conifer forests and dramatic rock formations along Northern California’s inner Coast Range.

Biden’s actions put in place stronger federal protections for areas that were left out when each monument was initially set aside by then-President Obama, in 2014 in the case of the San Gabriel Mountains, and the following year for Berryessa Snow Mountain. Advocates say the designations will expand underserved communities’ access to open space and better preserve sacred and historic Indigenous cultural sites. The move also came as the commander in chief has sought to boost his conservation record heading into the presidential election.

“It’s a huge deal on so many levels,” said Sen. Alex Padilla, who had previously introduced legislation that would have expanded both national monuments. That legislation remains active, but lacks the Republican support in Congress to bring it to the finish line, he said.

As a result, Padilla and Rep. Judy Chu of Monterey Park last year urged Biden to bypass Congress and instead issue a presidential proclamation under the Antiquities Act of 1906, which the president is expected to do Thursday.

“I’m exceptionally proud to have worked in Congress with Sen. Padilla, other local, state, and federal elected officials, and many local advocacy groups for over a decade to highlight the significance of the San Gabriel Mountains to our environment, economy and health,” Chu said in a statement.

Millard Falls, at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains near Altadena, is part of the expanded national monument.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

The expansion of each monument was the culmination of years-long grassroots campaigns by conservation organizations, community groups and tribes, Padilla said.

“A lot of work went into the initial monument designations under President Obama, but the areas that are being added now were part of the initial vision, just not included in the initial designation,” he said. “So it’s finally completing the vision.”

The move adds nearly 106,000 acres to the 346,000-acre San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, which sits within an hour’s drive of 18 million people, extending its boundaries to the edge of San Fernando Valley neighborhoods including Sylmar and Lakeview Terrace, as well as the city of Santa Clarita. Those are some of the hottest regions within L.A. County, and home to communities of color that have historically lacked access to nearby green spaces, said Belén Bernal, executive director of Nature for All, a coalition of environmental and community groups that has long campaigned for more parks and safe outdoor opportunities, including the expansion of the monument.

“As a Latina, I believe that we, people of color, given our income status and that a lot of our family members are immigrants to this country, we have been deprived of nearby nature in our neighborhoods,” Bernal said.

Stretching from Santa Clarita to San Bernardino, the San Gabriel Mountains watershed provides Los Angeles County with 70% of its open space and roughly 30% of its water. Already, the Angeles National Forest attracts nearly 4.6 million visits a year — more than Grand Canyon or Yosemite National Park. The added protections will help ensure equitable access to the San Gabriels’ cool streams and rugged canyons, while also preserving clean air and water, Bernal said.

Leaders of Indigenous groups — including the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians and the San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians Gabrieleno/Tongva — were part of the coalition that pushed for the expansion.

“Expanding the monument helps protect lands of cultural importance to my people, who are part of this nation’s history and who have cared for these lands since time immemorial,” said Rudy Ortega Jr., president of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, in a statement heralding the announcement. “It also further protects areas that are critical for our environment and the wildlife and plants that depend on this landscape.”

The expansion will protect Bear Divide, a slot in a ridgeline overlooking Santa Clarita that is used by thousands of migrating birds as they make their way from Central America toward the Arctic. It will also preserve habitat for black bears, mountain lions, coyotes and mule deer, along with rare and endangered species, including Nelson’s bighorn sheep, mountain yellow-legged frogs and Santa Ana suckers.

The Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument, seen here at Lake Berryessa in Northern California, was first designated in 2015.

(Eric Risberg / Associated Press)

Newly included in the Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument, Molok Luyuk is the sacred ancestral home of the Patwin people — which include the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, the Kletsel Dehe Wintun Nation and the Cachil Dehe Band of Wintun Indians — that also served as an important trade and travel route for other Indigenous groups. As part of the agreement, the ridge will be officially renamed from Walker Ridge to Molok Luyuk, which means Condor Ridge in the Patwin language.

The expansion provides the Patwin tribes with the opportunity to co-steward Molok Luyuk with the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the monument, Anthony Roberts, tribal chairman of the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, said in a statement.

“Notably, the renaming of Walker Ridge to Molok Luyuk recognizes the Patwin ancestry of this area of California, whose traditional territory stretches south from these hills to the shores of San Pablo Bay and east to the Sacramento River,” he said. “It also highlights the restoration effort being made by our Tribes to reintroduce the California Condor to the ridge,” he said.

Molok Luyuk was initially left out of the 2015 monument designation because of multiple attempts to put a wind energy project on the ridge. The project was eventually shelved over a variety of issues, said Sandra Schubert, executive director of Tuleyome, a conservation nonprofit that has been trying to win protections for the piece of land for more than 20 years.

As the spot where two tectonic plates meet, Molok Luyuk has unique soils, plants and geological features that make it a popular spot for scientists to study, Schubert said.

“Think of walking like 100 yards, and you’re literally walking through millions of years of history because of the geology,” she said. “That unique geology also leads to unique, rare species, especially of plants.”

Although Molok Luyuk makes up about 0.2% of California’s acreage, it supports a staggering 7% of the state’s native plant diversity, including rare plants like the adobe lily and Purdy’s fritillary, as well as the world’s largest known stand of MacNab cypress, said Jun Bando, executive director of the California Native Plant Society, which was also key in pushing for the expansion.

The designation also paves the way for the piece of land to be included in Berryessa Snow Mountain’s national monument plan, which helps ensure it is adequately protected, she said.

“Molok Luyuk is an area that is sacred to the local tribes and it’s also really unique in terms of the degree of biodiversity that it supports,” Bando said.

Vice President Kamala Harris said in a statement that she fought for public land protections as a U.S. senator from California and thanked both Biden and local advocates for making the expansions a reality.

“These expansions will increase access to nature, boost our outdoor economy and honor areas of significance to tribal nations and Indigenous peoples as we continue to safeguard our public lands for all Americans and for generations to come,” she said.

Big picture, the national monument designations are key to the goal — put forward by a team of international scientists and adopted by California — of protecting 30% of lands and coastal waters by 2030, Bando said.

“This goal isn’t a ‘nice to have,’” she said. “It’s part of urgent international action to address the intertwined crises of climate change and extinction.”