Rafah’s population has swollen after hundreds of thousands of desperate families fleeing from the rest of Gaza sought what shelter they could from Israel’s relentless attacks.

The southern city has not been spared Israeli attacks from the air as Israel has threatened for weeks to invade it by land, spurring international concerns about the potential impact on Palestinian civilians there.

Under pressure from its allies in the United States and the West as well as pressure from its neighbour Egypt, Israel appears to have permitted the building of a refugee camp at Khan Younis, north of Rafah.

About 40,000 tents are reported to have been bought by Israel while others, of unknown provenance are already in place outside Khan Younis. How 1.4 million people would be housed in those tents remains unclear, as do the details of an Israeli announcement on Wednesday that it had determined other, “safer” zones for the evacuees.

Gaza’s fate beyond any Israeli assault on Rafah remains unknown.

Why Rafah?

Far-right and ultranationalist members of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s cabinet, whom he relies on for the survival of his coalition government, are publicly invested in a ground offensive on Rafah, reacting angrily to any implication that it might not happen.

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir reportedly told Netanyahu that not launching a land assault on Rafah meant he would have failed in his mission to protect Israel.

But the Israeli government also reportedly told Egypt on Friday that it would give a “last chance” to a potential captive release deal before invading, according to The Times of Israel, which quoted an unnamed Israeli official as saying “a deal in the near future or Rafah”.

Benny Gantz, a member of the war cabinet who is seen as a more moderate figure and entered the war cabinet only after the war on Gaza began, said on Sunday: “Entering Rafah is important in the long struggle against Hamas. The return of our abductees, abandoned by the 7.10 [Netanyahu] government, is urgent and of far greater importance.” A deal to return the captives, he added, should be taken so long as it does not require that the war end.

Israel says four brigades of Hamas fighters and the group’s leaders remain in Rafah, shielded by a number of captives taken from Israel on October 7, which justifies an assault in defiance of international concern.

Israel has previously sought to combat Hamas’s armed wing, the Qassam Brigades, at other locations, such as al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City, and declared them “cleared”.

Weeks later, Israeli soldiers and tanks would return to these same locations, killing more civilians and destroying more as the army “recleared” the areas.

“Netanyahu is coming to a strategic political intersection where the centrist bloc in the emergency government – led by Gantz – are pressuring for a hostages deal while the far-right section led by Smotrich and Ben-Gvir signal that a deal that would prevent Israel from initiating an operation in Rafah would not be acceptable for them,” Eyal Lurie-Paredes of the Middle East Institute said.

Judging by Netanyahu’s past, he will at all costs prioritise maintaining his coalition, which has a slight Knesset majority of 64 of 120 seats, Lurie-Paredes continued.

“His calculation is simple: He has full political dependency on Smotrich and Ben-Gvir for any future coalition after alienating most other factions of Israeli politics due to his ongoing corruption trial. Smotrich and Ben-Gvir are very aware of Netanyahu’s political dependency on them and use it to gain much influence on the government’s policy even though they are not part of the war cabinet,” he said.

Settler ambitions

Since Israel withdrew its 21 settlements and 9,000 settlers from Gaza in 2005, the enclave’s boundaries have held firm while Palestinians in the occupied West Bank have been divided up and isolated from each other by settlements, illegal under international law, whose settlers attack Palestinian towns violently, and decisions by Israeli authorities.

Many Israeli settlers have come to see the current conflict as an opportunity to reverse that withdrawal from Gaza, but how much impact they have on decision-making is unclear.

“There has been an Israeli movement to settle in Gaza for decades, so the idea is not new at all. What’s new is the plausibility of the notion,” said HA Hellyer, senior associate fellow at the London-based Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies.

Several Israeli organisations advocate for the return of Israeli settlers to Gaza, such as Nachala, a group that organised a conference in January calling for Gaza settlements that was attended by Israeli government ministers and members of parliament.

The director of Nachala and a leading figure in the movement, 78-year-old settler Daniella Weiss, says more than 500 families have already “signed up to settle Gaza”.

She also stated that no Palestinians will remain within the enclave after settlement.

While taking the entirety of Gaza may be a step too far, some analysts say Israel or its settler movement may have an eye on splitting Gaza in two and taking the north, cramming the entire Palestinian population into even less space than they had when Gaza was called “the world’s largest open-air prison” by international organisations, including Amnesty International.

The idea has also been suggested on several occasions by Weiss, most recently in a video filmed by Middle East Eye in February.

In the video, Weiss outlines settler plans to march into northern Gaza, taking it piecemeal while Israeli soldiers look on, much as they continue to do as settlers attack people, burn property and encroach on Palestinian land in the occupied West Bank.

“Settling just in the north of Gaza would make such settlements more strategically defensible in comparison to other parts of Gaza,” Hellyer said.

“The notion is serious. We have an Israeli government in office right now that is particularly hostage to far-right elements in order to stay in power, and we don’t have an opposition that is sufficiently resistant to ensure that such an eventuality does not take place.”

In March, Zvika Fogel, head of the Knesset’s National Security Committee, told Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, that “Israel must end the war when Jews settle in the entire northern Gaza Strip”.

Much of northern Gaza was destroyed in the early months of the fighting and now lies in ruins, split off from southern Gaza by a corridor created by the Israeli army and called the Netzarim Corridor.

Last week, the Israeli army replaced the Nahal Brigade, which was operating in the Netzarim Corridor, with two reserve brigades, ostensibly to prepare for future operations.

Israeli security forces initially looked on in late February when a number of settlers stormed the Beit Hanoon (Erez in Hebrew) crossing into northern Gaza, some getting as far as 500 metres (550 yards) inside the Strip and erecting haphazard wooden structures that spoke as much to their symbolism as it did to the setters’ serious territorial ambitions. Eventually, Israeli soldiers forced them back to Israel.

While Netanyahu has denied that Israeli settlements in Gaza are an option, many leading Israeli politicians are known to support the suggestion.

A poll carried out by the Jewish People Policy Institute in January showed that 36 percent of Jewish respondents in Israel believed that Israel should take control of Gaza and 26 percent said they supported the reconstruction of the former settlements.

However, thousands of Palestinians have stayed in northern Gaza and Gaza City, determined to never abandon their homes, and the return of civilians to northern Gaza has been one of Hamas’s central demands during ceasefire negotiations.

Humanitarian consequences

Focusing on the scenario of a ground offensive in Rafah, Israel’s Western allies have retained their concerns about the safety of the 1.4 million people sheltering there after fleeing Israel’s attacks on the rest of Gaza.

Regardless of whether a ground assault happens, conditions in Rafah are dire and not enough is being done about them, Louise Wateridge, a Rafah-based spokesperson for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), told Al Jazeera.

People lack food, sanitation, potable water, adequate shelter and healthcare and have had their suffering compounded by a heatwave, which has seen temperatures exceed 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit).

The US and others have said Israel must evacuate civilians in Rafah before a land invasion despite there being little evidence that Israel has taken humanitarian considerations into its calculations since October.

Israel for months has been refusing to cooperate with UNRWA, the best placed international agency to deliver aid in Gaza as it has both the teams and the infrastructure to do so.

“UNRWA is not only the backbone of the humanitarian operation in the Gaza Strip but also the glue that holds it together,” Wateridge said. “Nothing would be delivered or provided without the coordination of our UNRWA colleagues here.”

“The community engagement involved with the agency’s work is very unique. People in Gaza know UNRWA, and no other agency has this relation,” Wateridge added.

It is not clear what agency could administer any camps established for Palestinians evacuated from Rafah or support the traumatised population that will be sheltering there.

Shortfalls in aid crossings into Rafah have been the subject of repeated international criticism of Israel, including that from its closest international ally, the US. In April, Israel agreed to reopen the Beit Hanoon (Erez) crossing as the only access point for aid to enter northern Gaza and a crossing built for pedestrians.

Farther south, a pier is being assembled by the US in the Mediterranean Sea to be towed to Gaza to be used to deliver humanitarian aid.

Aid officials have told The Guardian newspaper that the pier will not be positioned in northern Gaza, where the threat of famine is most acute, but at the Netzarim corridor in central Gaza, where the Israeli army is stationed, ostensibly so that it can guard the supplies.

According to sources quoted by the paper, there are growing fears that the pier will be used to deliver aid to the displaced of Rafah rather than to the north, where it is most needed.

“One of the key arguments for having a dock was to put it farther north so that suppliers could come in more directly to the north,” a UN official said, adding that what was actually being proposed looked more like a “smokescreen to enable the Israelis to invade Rafah”.

Could Israel take Gaza and retain international support?

Protests around the world against the war show no signs of abating, and criticism from governments towards Israel continues to increase.

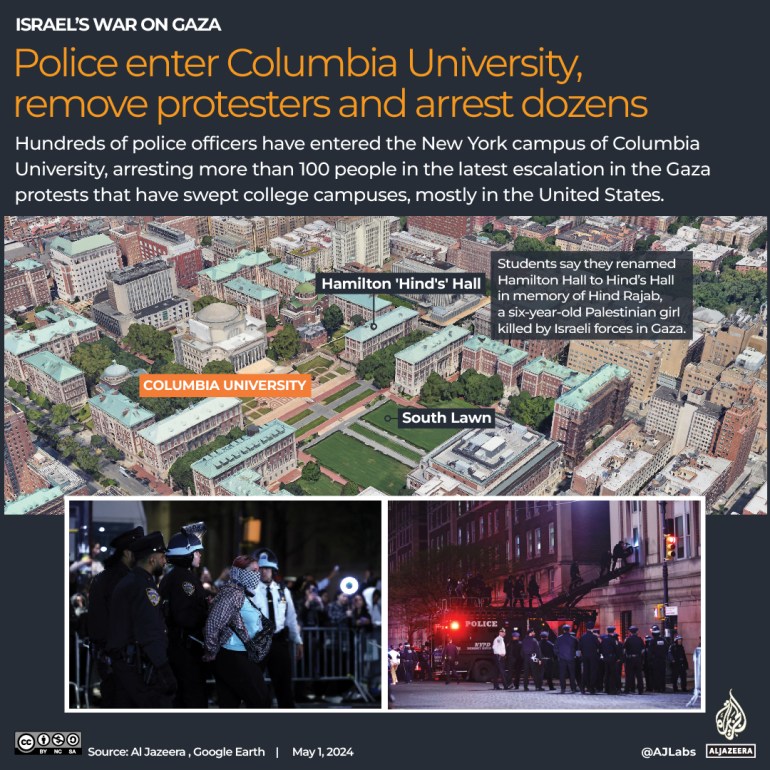

In the US and Canada, protests on university campuses are growing and have been in the spotlight for the past two weeks.

Nevertheless, even as criticism increases, the US government has remained by Israel’s side.

It has used its veto in the UN Security Council several times to block ceasefire proposals and in April was the only member to block a proposal for Palestinian statehood.

Whether Israel’s die-hard allies will be able to stem the tide of anger at its destruction of Palestinian lives and infrastructure in Gaza as well as in the occupied West Bank remains to be seen.

So far, despite an increasingly vocal public campaign for Western states to confront Israel over its actions in Gaza, governments have offered only the most tremulous criticism.