Another colleague walking by overheard her and interrupted, “That’s the devil talking,” before referencing a Bible passage.

“It was kind of intense,” Brenneman recalled to The Times. “Working on this play, which is talking about a specific history and also multiple world religions, there’s going to be rigidity. And I welcome it.”

Running through May 12 at Costa Mesa’s South Coast Repertory, “Galilee, 34” takes place months after the crucifixion, when Jesus’ family and followers are trying to figure out how to proceed after the sudden death of their leader. Where should they travel next to share his teachings? Why were his sermons always so confusing? And should one of them take up the mantle, even though it’s what got him killed?

As this group of Jews create what becomes the foundation of Christianity, they argue about the real meaning of his message and lament his sharp temper. They swear freely, accuse one another of being self-serving and criticize each other for not believing hard enough or in the correct way.

Despite Mary Magdalene’s disclaimer from the stage that “None of this happened,” the creative team behind the world premiere readily acknowledges that such a portrayal of biblical characters has the potential to be controversial — or even blasphemous — to some believers, especially in Orange County, home to substantial Catholic, mainline Protestant and evangelical Christian populations.

“It’s written with an enormous amount of care and thoughtfulness, and a searching curiosity about each of the characters and their quest to find what God wants from us,” said director Davis McCallum.

“Of course, you never really can predict what people will find offensive, but I think that people of faith who come and see the production will recognize it as a very honest wrestling with the questions of faith and the search for peace within and between people.”

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Playwright Eleanor Burgess began writing “Galilee, 34” in 2019, the year she became a mother. “Something about being pregnant and giving birth made me think about how the Virgin Mary was a real mom, who had a real son and had to watch him get killed by state violence,” she said.

“Thinking about her made me think about all of them as just real people — human beings who had a sincere longing for contact with the divine but who were also capable of jealousy, failure, doubt, grief and disagreement, and whose decisions had repercussions that still reverberate around the world.”

Burgess, who grew up in a Jewish-Catholic household and studied religious and intellectual history as a Yale undergrad, wrote the play amid “intense” reading of primary texts (the Bible, the Mishnah, the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Gnostic gospels), the writings of Jewish and Christian theologians and scholars, and historical research on the daily life of people in ancient Judea under the Roman Empire.

But it was a real-life exchange of ideas, not Burgess’ extensive syllabus, that crystallized the play’s premise. “I gathered a bunch of friends from different faith backgrounds — ordained ministers, people who’ve read the Bible countless times, people who’ve never read it and were raised in atheist or Jewish households — and, over coffee and bagels, we read passages from the Gospels together,” she explained. “Hearing them talk about their interpretations, and how they were taught in Sunday school or elsewhere, was really the most generative stage of the research.

“When these stories are taught, they get sanitized and flattened,” she continued. “The answers are so obvious and everyone gets sanctimoniously made into perfect saints, which is sad because, to me, the humanity is not sacrilegious at all. It’s more beautiful and inspiring, and much more likely, that they weren’t perfect and they’re trying to be better, even though it’s complicated and gnarly and incredibly uncertain.”

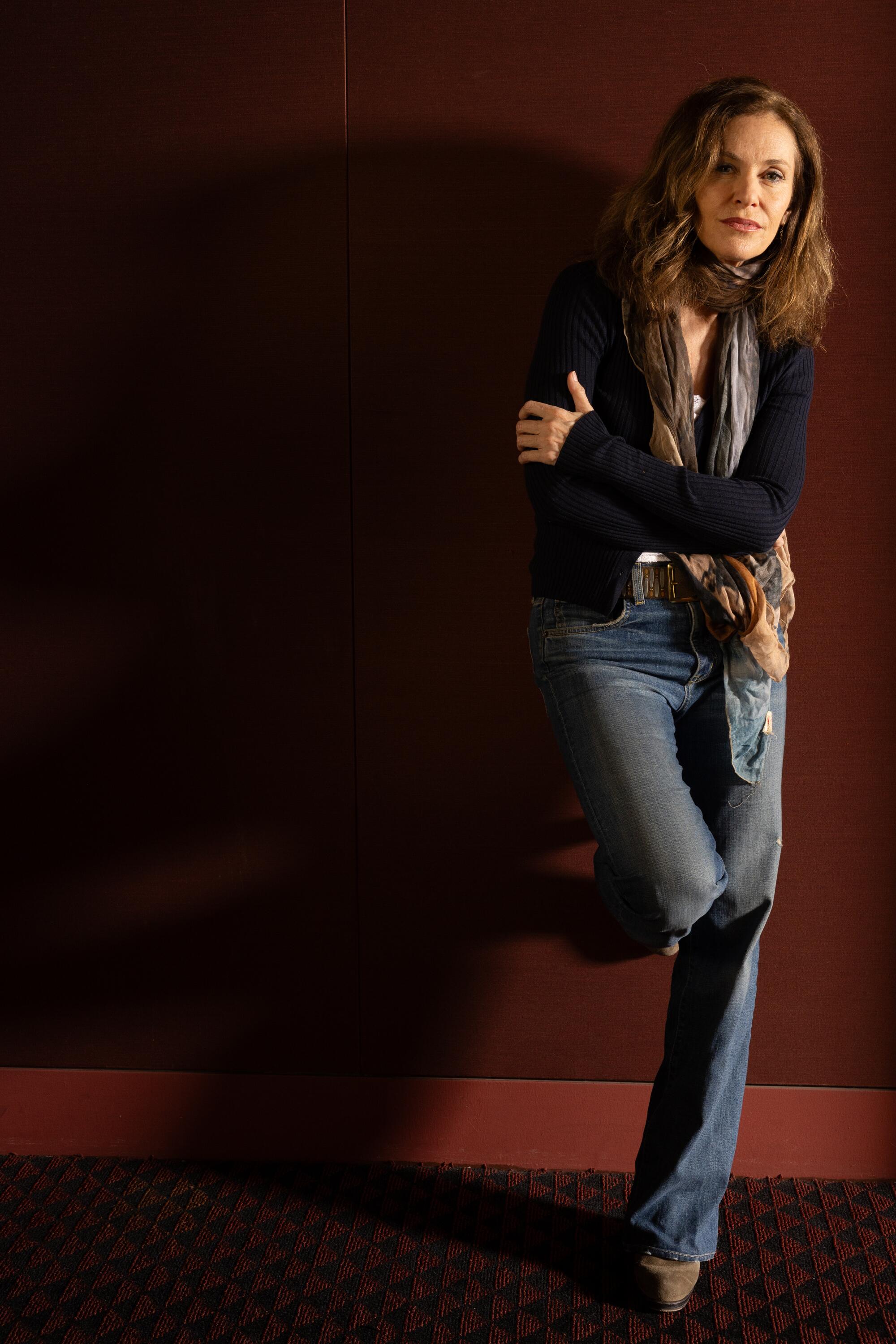

Amy Brenneman plays Miriam of Nazareth in “Galilee, 34” at South Coast Repertory.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

That ear for imperfection is most clear in the play’s portrayal of Jesus’ mother, Miriam. “She’s a Jewish mother — she’s pushy, she’s got an agenda, she thinks her son literally walks on water,” said Burgess with a laugh.

“In the Bible, she’s the person who encourages him to do his first miracle. So I think of her as this very righteous, fiery woman who cared enormously about justice and raised a son she was tremendously proud of, and then watched that son get killed, partly for teaching the stuff she had taught him.”

“Those images on stained glass where she’s blond and looking down, or the fact that she’s a symbol of passivity, acceptance and the total subjugation to the will of the Father — that’s what we’re pushing back against,” added Brenneman. For example, Miriam balks when Saul suggests that her son was a sacrificial lamb whose murder by the Romans was allowed by God; this foundational Christian belief is “a brand new idea to her, and it’s heartbreaking to hear someone spin it that way to a grieving mother.”

“Galilee, 34” further disrupts the scriptures by allowing its characters to break the fourth wall and correct the record, as it were. Mary Magdalene, here named Miri of Magdala, seizes the opportunity to announce that she’s not a prostitute, as long thought, but a wealthy divorcee. (The source of the confusion? A pope’s translation error.)

“She, for some reason, isn’t very palatable to any of the people that she’s surrounded by, and I don’t know that the audience will necessarily like her either,” said Teresa Avia Lim, who plays Miri.

“Here, she’s much more fleshed out than the cardboard version of her that was presented to me in Sunday school; she was more like Jesus’ wife, lover or romantic intimate partner, and I had never heard that before. But I love that, in this play, she challenges the notion that a woman must be ‘pure’ in order to have a deep, true connection to God.”

One character could draw criticism for his very inclusion: Jesus’ brother Yacov of Nazareth, also known as James the Just. Theologians have long debated his existence and connection to Jesus, arguing alternately that the two were merely “brothers in Christ,” distant relatives and close siblings. The play opts for the latter, and Yacov, played by Eric Berryman, claims that Jesus didn’t always practice what he preached.

“What is it like to grow up with the Messiah as your brother?” said Burgess. “Naturally, everyone is looking to him to carry on Jesus’ legacy, but he remembers a version of Jesus that’s not as perfect as what everyone wants to hear. There’s love, but there’s also sibling rivalry and pettiness and annoying, decades-old grievances. Should he push all that aside to finally step into the spotlight, even though that’s what got his brother killed?”

Teresa Avia Lim plays Miri of Magdla in “Galilee, 34.” (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Eric Berryman plays Yacov of Nazareth in “Galilee, 34.” (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

For future stagings of “Galilee, 34,” the script includes a note about casting: “Given that this play takes place in the crossroads of the Ancient World, and that all of this has since become a story that matters to people from every continent, this is an occasion where ‘color-blind,’ or color-open casting is the best choice — and many accents are welcome. Let this be a global story.” (At South Coast Rep, Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist’s mother are played by Asian actors, and Jesus’ brother is played by a Black actor.)

“From the very beginning, people have been taking these stories away from a specific historical and ethnic context, and making them universal,” said Burgess of the casting. “For better and for worse, all people have ever done with this man and this story is to say, ‘This is mine now; this is how I see it.’ So I’m just doing exactly that. This is how I see this story. This is how I want to tell it.”

So far, at least, no backlash against the play or the theater has developed, either when the piece debuted as a reading at last year’s Pacific Playwrights Festival or when South Coast Repertory announced to subscribers its inclusion in the season. Said festival co-director Andy Knight of programming the production, “There wasn’t hesitation, there was excitement.”

Raviv Ullman, left, Ben Pelteson, Eric Berryman, Amy Brenneman and Christopher Cruz in “Galilee, 34.”

(Robert Huskey / South Coast Repertory)

“People who want to be offended by things will always find things to be offended about,” said Burgess. “I didn’t make any choices hoping to provoke or piss people off. The perspective from which I’m writing is one of enormous respect for the project of faith and religion.

“This is an empathetic look at the struggles that come with faith being central to your life, so I would hope that, for a lot of people with religious backgrounds, it’s actually a story that reflects their experiences much more than a lot of what we see onstage. I live in New York; I’ve seen plays that dismiss faith by full on treating it as a punchline!”

In that way, the choice to debut “Galilee, 34” at an Orange County theater “is mirroring what the play is about,” said actor Berryman of the characters’ debate about where to evangelize. “This play talks about preaching a particular message into the lion’s den, where it may not be well received, but in the end, that’s exactly where it needs to go and has to go. I feel like all art has to do that.”

And for audiences who aren’t religious, the historical play is still plenty entertaining. “It’s like church,” said Burgess. “All are welcome.”

“Galilee, 34” playwright Eleanor Burgess, front, with actors Amy Brenneman, left, Teresa Avia Lim and Eric Berryman at South Coast Rep.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)