You can a) nicely ask the analysts to pay less attention to subscriber figures and instead focus on something else, like revenue and profits; or b) just stop reporting your subscriber numbers every quarter.

Netflix, the world’s largest subscription-based streaming service, is going with the second option, starting in the first quarter of 2025.

The Los Gatos, Calif.-based company gained 9.3 million subscribers in the first three months of the year, bringing its total paid membership base to 270 million globally. That’s a bigger gain than analysts were expecting, according to FactSet data. But it’s not what Netflix wants its shareholders to fixate on.

Instead, Netflix would prefer that the market judge its business based on metrics including sales and free cash flow (a measure of profitability), which is a better indicator of the company’s overall health. And if investors want to get an idea of whether Netflix’s shows, movies and app are connecting with viewers, the better statistic to look at is “engagement” (e.g., how much time customers spend with the platform), not subscriber data.

You could look at this as a real spiking-the-football moment for Netflix. According to Wedbush Securities analysts Alicia Reese and Michael Pachter, this signals the arrival of Netflix’s long-awaited pivot “from a high-growth, low-profit business to a slow-growth, high-profit business,” even if that transformation is not yet complete.

“Netflix has managed to establish a virtually insurmountable lead in the streaming wars, and we expect competitors to continue to flail while trying to replicate Netflix’s business model,” Reese and Pachter wrote in a note to clients. Netflix stock has risen nearly 70% in the last year, closing Monday at $554.60 a share. Wedbush’s 12-month target for Netflix’s stock is $725.

The much-discussed change doesn’t mean Netflix’s membership numbers are going into a black box. Greg Peters, the company’s co-chief executive, told analysts last week that the firm would “periodically update when we grow and we hit certain major milestones … It’s just not going to be part of our regular reporting.” The change also isn’t taking place immediately. It’s coming early next year, giving Wall Street time to adjust.

As some commentators have noted, there’s a certain amount of irony afoot here. Netflix has typically been more transparent with data than other streaming services, especially when it comes to disclosing how many people watch their shows. Now Netflix is going backward, at least with subscriber additions, even as it becomes increasingly forthcoming with viewership reports.

But the most interesting thing about Netflix’s transition is how it reflects broader changes in the way the market treats streaming.

When the streaming wars started, legacy media companies were jealous of Netflix’s soaring stock price. The thought was: investors were rewarding Netflix for its subscriber growth; if we show subscriber growth, our stock will go up. Media companies including Disney, (then AT&T-owned) WarnerMedia, Paramount Global and NBCUniversal were willing to lose vast sums of money to fuel growth.

That thinking has changed. Now, profitability is the top priority across the industry, and traditional media organizations have severely cut costs to get their cash flows under control, leaving Netflix to extend its lead.

The problem is, old habits are hard to break. People who cover Netflix, including analysts and journalists, understand that subscriber counts aren’t the same as money. But the sub figures are sexy and easy for general readers to understand, and more data is better than less, right? For example, the shift means Netflix will no longer report average monthly revenue per user on a quarterly basis, which has been a valuable way to compare the health of various services.

On the flip side, Netflix is adding annual revenue guidance to its reporting.

There are clear reasons why Netflix might want to avoid being judged by the number of subscribers it draws in and retains every quarter. For one thing, sub counts can suffer from short-term volatility. In other words, they could go down if Netflix raises its prices by a lot, or if, say, a big country suddenly becomes a non-market, as Russia did when it invaded Ukraine. In 2022, when Netflix reported losing subscribers for two straight quarters, it triggered a major sell-off. Not just of Netflix’s stock, but of the whole streaming video sector.

This came to be known as “the great Netflix correction.” Netflix would surely like to avoid repeating that history when its user growth stalls again. In recent quarters, the subscriber numbers have been boosted in part by the company’s efforts to crack down on password sharing, plus its promotion of the ad-supported tier, which reduces cancellations in the wake of the aforementioned price increases.

The effect of converting freeloaders to paying customers will eventually wear off, though Netflix still has room to grow. The company still accounts for less than 10% of U.S. television usage, according to Nielsen. People actually spend more time watching YouTube, which is free.

Netflix’s stock has long been sensitive even to subtle signs of stress. Back in the early days of the company’s push into original content, the shares took a dive seemingly after a negative New York Times review of its “Arrested Development” reboot. The stock remains volatile, and expectations are high. Netflix last week reported results that beat Wall Street data in terms of revenue, profitability and subscriber additions. The shares still fell.

Entertainment companies are always trying to work the refs, especially in the streaming era. Warner Bros. Discovery thinks it doesn’t get enough credit for its progress toward making Max (formerly HBO Max) healthy. Others say that Warner Bros. Discovery’s numbers, which show profitability from its direct-to-consumer segment, are hard to parse because they include traditional HBO. Peacock still seems to get points, at least in the press, for gaining subscribers, despite losing massive amounts of money.

Now Netflix is trying to shift market expectations again. But this time, on its own terms.

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

David Ellison’s journey from trust fund kid to media mogul vying to buy Paramount. Skydance Media CEO Ellison, son of billionaire Larry Ellison, has emerged as a strong contender to take over the iconic Paramount studios.

Journalist who accused NPR of liberal bias resigns from the network. Longtime editor Uri Berliner, suspended after the publication of his Free Press essay that said the nation had lost trust in the public broadcaster, announced his departure from the network.

‘The fairy dust fades away’: Why the people who play Disneyland’s costumed characters are unionizing.

Character performers at Disneyland Resort have filed a petition for a union election with the National Labor Relations Board, per the Actors’ Equity Assn.

David Zaslav earned $49.7 million in a year when Warner Bros. Discovery struggled. Zaslav’s compensation, like other Warner Bros. Discovery executives, was closely tied to free cash flow, a measure of profitability that reflects cost cutting.

Number of the week

If Sony teams up with Apollo Global Management’s $26-billion bid for Paramount Global, it would provide a substantial boost to the private equity giant’s proposed takeover.

Apollo had already expressed interest in purchasing Paramount in a deal that would include the entertainment company’s $14 billion in debt. But Paramount has instead engaged with David Ellison’s Skydance Media, the Santa Monica-based company best known for producing “Top Gun: Maverick.” Ellison has a 30-day exclusivity window to reach a deal for Paramount (the time frame could be extended).

Under Ellison’s proposal, Skydance would acquire Shari Redstone’s National Amusements Inc., the holding company that owns 77% of Paramount’s shares. Paramount would then acquire Skydance for $5 billion in stock, up from the $4 billion valuation estimated during a 2022 funding round led by KKR. Redstone prefers the Ellison option because she can cash out. Many investors are displeased with the Skydance framework because, as they see it, they’d be left with diluted shares in an uncertain enterprise.

Apollo’s bid would be harder to ignore if it brought on Sony, a Japanese electronics and entertainment giant that already owns a U.S. movie and television studio. But a pairing of Sony and Paramount would likely invite regulatory scrutiny, even though the Trump administration approved Walt Disney Co.’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox with minimal friction.

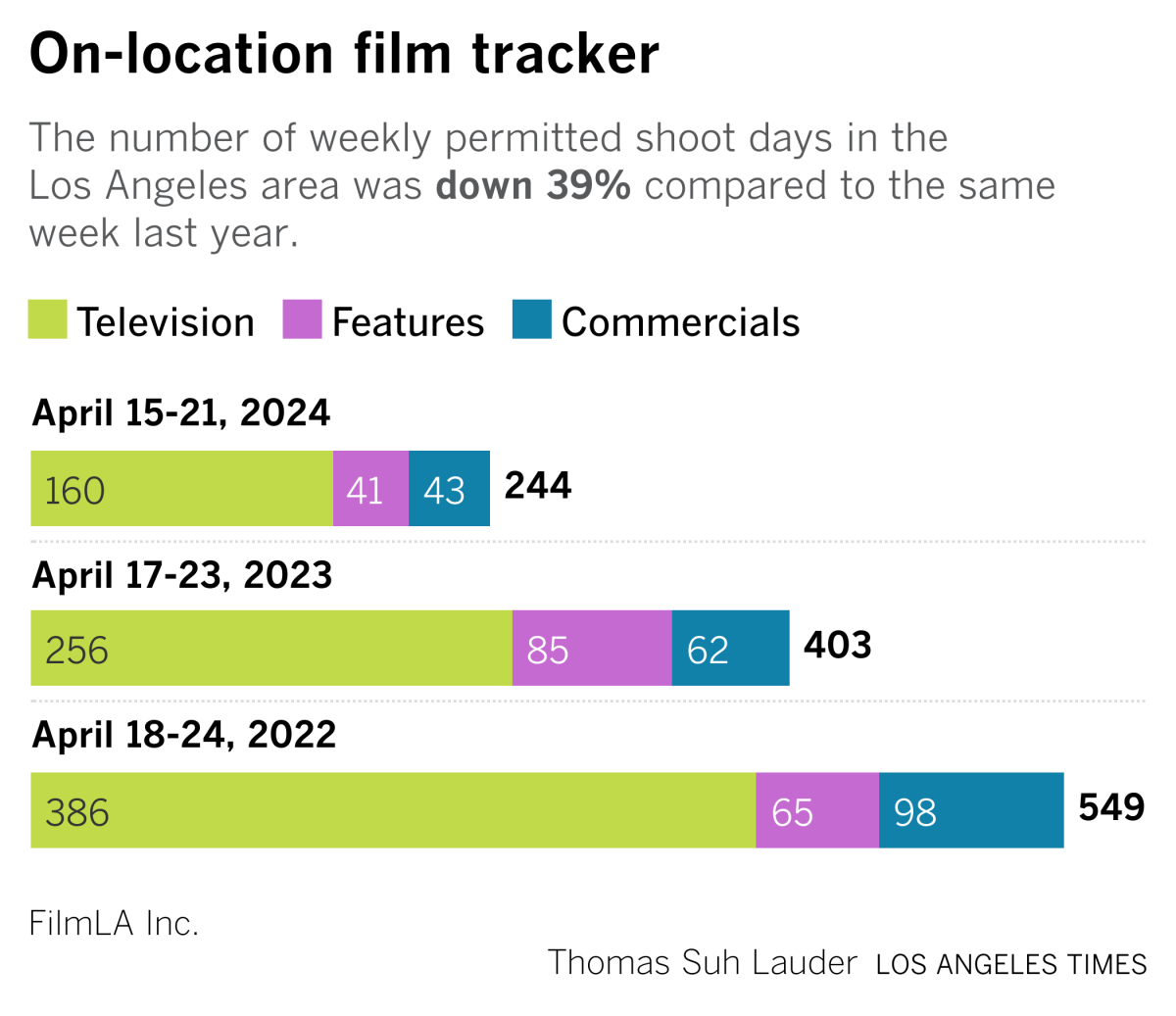

Film shoots

This week’s film production chart:

Best of the web

— It won Oscars and was a big supporter of independent, mission-driven cinema. What happened to the once-promising Participant Media? (Hollywood Reporter)

— Networks get creative to cover Trump’s trial. (New York Times)

— A now-former NPR editor critiqued the institution’s alleged shift toward advocacy. A media critic takes apart the polemic (or at least part of it). (Washington Post)

— Documents found on a North Korean server suggest U.S. studios may have unknowingly outsourced animation work. (CNN)

Finally …

Carolyn Cole, a veteran Los Angeles Times photographer who won a Pulitzer Prize for her coverage of civil war in Liberia, breaks down the depiction of her profession in A24’s “Civil War.” It’s a great read.