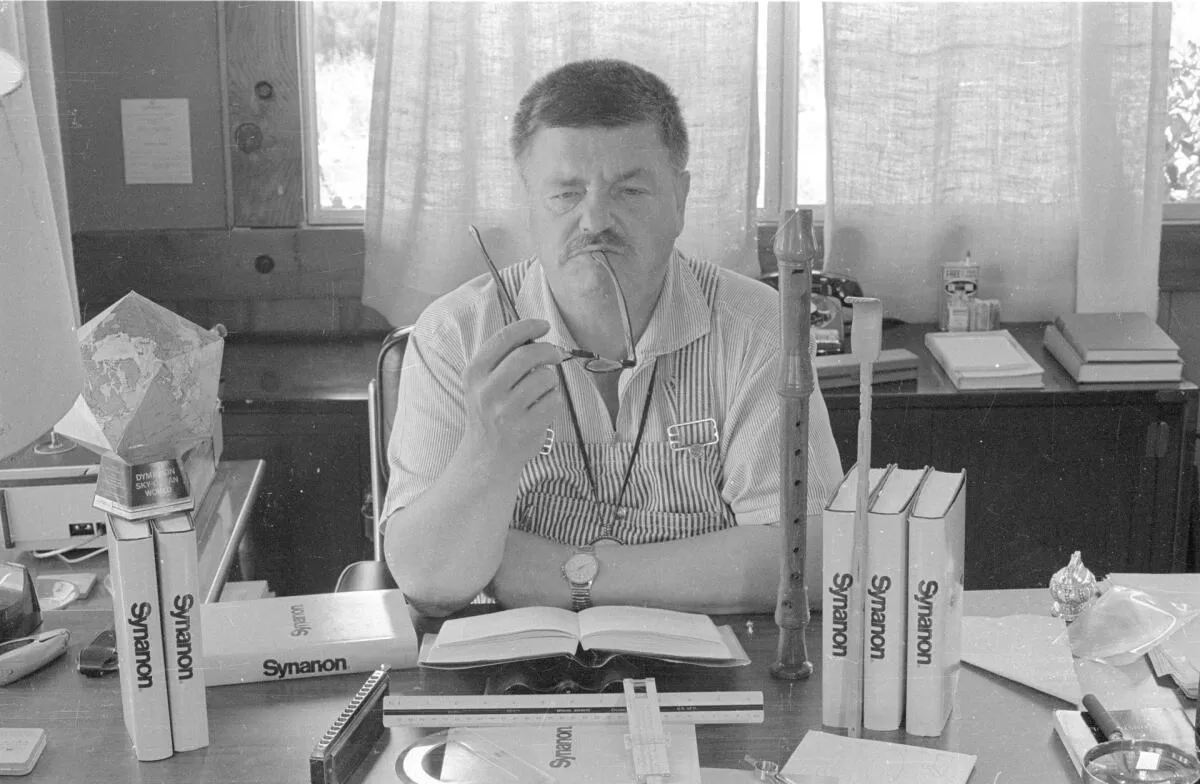

Over the next decade and a half, the group, named Synanon, expanded across the country and evolved into a self-help movement with thousands of members, including many who were not addicts but were simply drawn to its idealistic vision — no drugs, alcohol, or violence — and its primary ritual, an intensely confrontational form of group therapy known as “The Game.”

Yet by the late 1970s, Synanon had strayed dramatically from its original mission, devolving into a dangerous quasi-religious paramilitary organization whose devotees, beholden to Dederich’s increasingly erratic whims, were willing to undergo forced vasectomies, relinquish control over their own children and even attempt to murder a prominent critic by planting a rattlesnake in his mailbox.

The dark saga of Synanon is now the subject of a four-part documentary “The Synanon Fix,” concluding Monday on HBO. Directed and executive produced by Rory Kennedy, the series traces the group’s utopian origins and gradual descent into violence and manipulation. Arriving at a moment when the public’s interest in cults and high-control groups seems almost insatiable, “The Synanon Fix” offers a particularly grim, resonant twist on the familiar tale of the California dream gone awry.

The story “had this really dramatic, almost Shakespearean arc to it,” said writer and executive producer Mark Bailey, in a video chat with Kennedy from their home in California (the couple are filmmaking partners and have also been married since 1999). “The intentions and accomplishments for the first decade or so were really amazing. But where it ended up was really dark and destructive.”

Kennedy, who has made more than a dozen documentaries including “Ghosts of Abu Ghraib” and “Downfall: The Case Against Boeing,” said she was not particularly interested in “quote-unquote cult stories,” but was struck by the drama of Synanon’s 180-degree transformation. “In the beginning the pillars of Synanon were no drugs, no alcohol and no violence. By the end, they had bought more firearms than anybody in the history of California and had an open bar in the facility.”

Not only was the story dramatic, but it contained lessons about the dangers of blindly following a charismatic leader — a topic that feels politically relevant in 2024. Dederich was just such a figure, someone who built a community and inspired intense loyalty from his followers. “Because they’re tethered to him, where he goes, they go. And that’s the danger — as he starts becoming less stable, whether it’s from his alcoholism or mental illness, he takes Synanon with it,” Bailey said. “That felt, to us, like an important thing to say right now.” (Along with many members of her famous family, Kennedy, whose brother Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is running for president as an independent, endorsed President Biden last week.)

Kennedy and Bailey first learned about Synanon about a decade ago while reading “Straight Life,” an autobiography by jazz musician Art Pepper and his wife, Laurie, who met while getting clean in Synanon. “I had never heard of Synanon, but it’s right there on the beach, these folks with shaved heads, playing ‘The Game,’ which sounds like this pretty radical therapeutic treatment,” Bailey said. “I was instantly like, ‘Wow, what was this? And why have I never heard about it?’”

(HBO)

The documentary is woven together using extensive archival material — including news reports and visceral footage of members playing “The Game,” in which participants were aggressively pushed to be brutally honest about themselves and each other. It also features audio recordings of Dederich lecturing his followers over “the Wire,” the group’s internal broadcasting system, as well as first-person accounts from roughly 20 former members and interviews with journalists including Narda Zacchino, who wrote about Synanon for The Times.

Some former members were initially wary of sitting for interviews, Kennedy said, because “everybody was aware that there was a way to tell this story that’s pretty sensationalist.” But as she gradually won them over, more people decided to participate in the documentary — including Dederich’s daughter, Jady Dederich Montgomery.

After years of wrangling, the filmmakers were also able to secure access to Synanon’s archives, which included thousands of photos and “a treasure trove of extraordinary footage,” according to Kennedy. Because this happened just weeks before they were set to lock picture, they had to ask HBO for several more months and more money to recut the documentary. “To their credit, they agreed,” said Kennedy.

Interviewing people who spent years in Synanon playing “The Game” was both fascinating and challenging, she said.

“On average for documentaries, which I’ve now been doing for 25 years, the interviews are maybe two to three hours long. None of these were less than seven hours. Some of them went for nine hours, in like a sitting.” At times, Kennedy felt she was playing “The Game” with her subjects. “They would talk back to me more about how they were feeling about the interview as the interview was happening.”

Kennedy takes a straightforward approach in “The Synanon Fix,” allowing the story to unfold chronologically and spending time explaining the group’s origins before diving into the rattlesnakes and mate-swapping.

“This was a community that was taking a big swing at something that was really ahead of its time, in many ways, in terms of how it was treating drug addicts, who had been a very ostracized community,” said Kennedy. “They either went to jail, or they went to a mental hospital, or they died.”

Viewers learn how Synanon, which eventually moved into the historic Hotel Casa Del Mar in Santa Monica, began to attract a wider array of followers with the rise of the counterculture in the late 1960s. “Lifestylers,” as they were known, were people who joined Synanon because they were seeking a sense of purpose and belonging, not to treat their addiction. They saw the group as “a cure for loneliness and alienation,” said Bailey, and “The Game” as a way to heighten connection and sense of community. Some also donated large sums of money and professional services to the organization.

Throughout the ‘70s Dederich became increasingly dictatorial, making bizarre demands of his followers that had little to do with the group’s original mission. He required members to shave their heads and follow stringent diets and exercise regimens. Men were pressured into getting vasectomies and women into having abortions. After his wife died and he remarried, Dederich urged married couples to divorce and take new partners assigned to them. Eventually, Dederich fell off the wagon and rolled back the group’s ban on alcohol. Children were separated from their parents and had to shave their heads and play “The Game” just like adults, even if they lacked the ability to understand it. Some children allegedly were beaten and forced to do grueling labor.

Throughout the decade, Synanon faced mounting criticism including charges of kidnapping and child abuse, but its members grew ever more militant, stockpiling weapons and forming a militia called the Imperial Marines. The group made national headlines in 1978 when a lawyer named Paul Morantz, who had won a $300,000 settlement from Synanon, nearly died from a rattlesnake bite after Synanon zealots planted the animal in his mailbox.

The incident marked a breaking point for some adherents, but not all.

One of the more striking aspects of the series is how many former members still seem to believe in the Synanon cause — and remain grateful to Dederich, who died more than 25 years ago, for saving their lives.

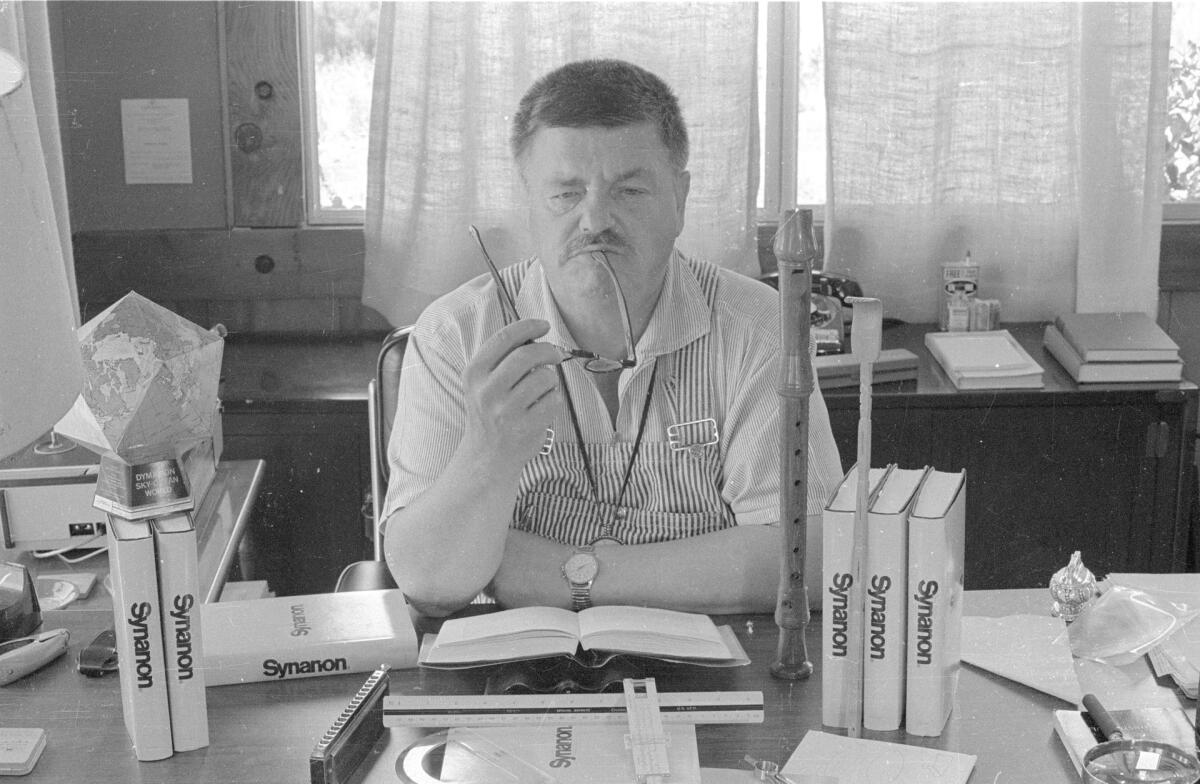

Rory Kennedy, one of the filmmakers of HBO’s “The Synanon Fix.”

(Jon Kopaloff / Getty for HBO)

The series’ central question is “Did the cure become a cult?,” and the filmmakers don’t entirely agree on the answer.

Bailey is not fully convinced Synanon fits the definition of a cult, if only because “there is something that feels too random and disorganized in what it was trying to do,” he said.

Kennedy is more confident in using the term. “I talked to enough people who felt like they compromised their moral compass to follow an idea that drove them in directions that they didn’t feel they should have gone in. That’s a defining quality of a cult,” she said, gently needling her husband for his more ambivalent take. “If you were there, you would have stuck with it to the end, clearly,” she said, laughing. “Sucker is what you are.”

Regardless of how they classify the group, the filmmakers see “The Synanon Fix” as a quintessentially Californian story about the kinds of spiritual seekers who’ve been drawn to the state for generations.

“You think of the people who move West as already kind of having searching in their DNA,” said Bailey. “We came out here about 14 years ago, but both of us were born and raised on the East Coast. And it was really something to get used to how you are allowed to just follow your own weird jam and everybody’s like, ‘Oh, that’s great.’”