Harry Edwards is one of those people. The Dodgers gathered Monday to hear him talk.

His name lives forever in Olympic lore, and not in a way the International Olympic Committee would prefer. In the 1968 Olympic Games, when American sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised fists of protest on the medal stand, Edwards was the man who prompted the gesture.

Before the Games, when Edwards announced the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) amid talk of a boycott by Black athletes, famed broadcaster Howard Cosell called Robinson and asked him why the runners could not turn the other cheek, as Robinson had.

The next week, Edwards said, Robinson appeared on Cosell’s show and endorsed the OPHR.

“Jackie built the bridge,” Edwards told me. “We crossed it.”

Carlos and Smith were vilified. Edwards received hundreds of death threats. He said that was the start of a 3,000-page file compiled on him by what he called “my presumptive biographer,” former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

This was two decades after Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. In some corners of the country, however, the right to vote had not followed the right to play ball. The pushback was not peaceful.

“That’s what Smith and Carlos were saying,” Edwards said. “We are better than our presidents being assassinated. We are better than our churches being bombed. We are better than civil rights leaders being shot dead in broad daylight.”

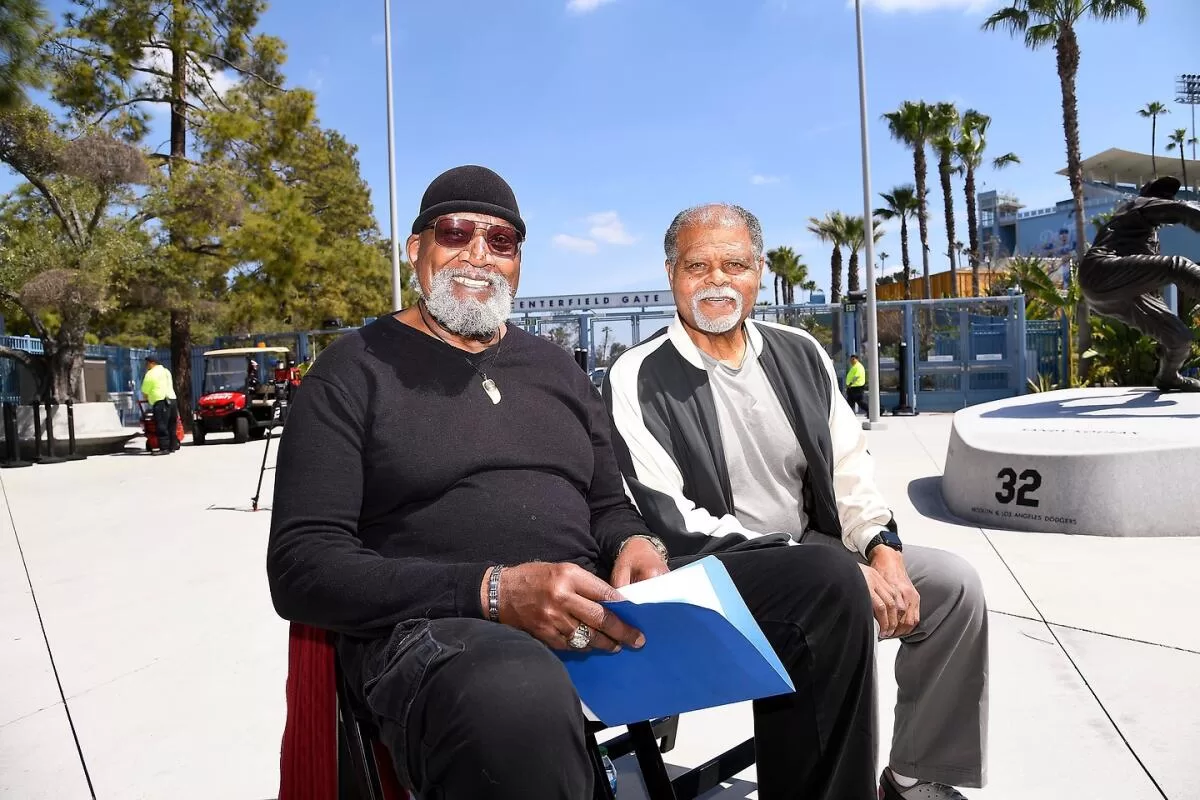

(Jon SooHoo / Dodgers)

The civil rights movement led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was grounded in nonviolence. King often credited Mahatma Gandhi for inspiring that journey.

“But most Black people didn’t know anything about Gandhi,” Edwards said. “For them, Jackie Robinson was America’s Gandhi model.”

In 1969, Edwards asked Robinson if he believed King and the civil rights movement appreciated what Edwards called the “monumental debt” owed for his contributions to social change on and off the field.

“In a profoundly modest, unassuming and almost self-effacing tone and countenance, he turned to me,” Edwards said, “and said, ‘Yes, I think they knew we were traveling the same path.’

“The fact, of course, is that Jackie blazed and paved that path.”

Edwards was one of the first to turn the study of sport into a legitimate academic discipline. In 1987, after former Dodgers general manager Al Campanis said on national television that Black people “may not have some of the necessities” to become a manager or general manager, the team promptly fired Campanis.

Peter Ueberroth, then the baseball commissioner, called Edwards for help. Edwards reached out to Campanis, to enlist him in developing a pipeline of Black prospects for the jobs of manager and general manager. The first name Campanis suggested: Dusty Baker, now a potential Hall of Fame manager.

Almost four decades later, on this Jackie Robinson Day, MLB had one Black general manager and two Black managers.

“That isn’t progress,” Edwards said.

Neither is this: Since the year Campanis spoke, the percentage of Black major leaguers has fallen from 18% to 6%. The reasons are many — spiraling costs, fewer neighborhood facilities, and the increasing popularity of other sports among them — and Edwards offered another.

“They offshored player development,” he said, “to academies in places like the Dominican Republic.” (This year, Latinos make up 30% of Major League Baseball players, and the league has a record six Latino managers.)

For the good of a badly divided country, Edwards hopes Americans take heed of the lessons Robinson taught us.

If not, Edwards said, “We are in for some very, very dark days,” perhaps as dark as the turbulent 1960s, the era that spawned the OPHR.

“We look to what a lot of people still consider the toy department of human affairs for guidance,” he said. “In the voices of children, and in the games they play, a lot of times we find resolution to some of the most important issues and challenges that we face.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts, center, introduces Ayo Robinson, rear left, the granddaughter of baseball legend Jackie Robinson, during a tribute at Dodger Stadium marking the 77th anniversary of Robinson breaking the color barrier in baseball.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

“We are still talking about race. We are still talking about ‘Can she do it?’ We are still talking about religion. We are still talking about the rich and the poor, rather than talking about ‘We the people.’ The words are there. We just don’t believe them.”

Edwards might not live to see whether our days turn dark. He is 81, and he is fighting bone cancer. He walks slowly and deliberately.

“I’m tired all the time,” he said.

He has fought injustice in the arena for a lifetime, from Jackie Robinson to John Carlos and Tommie Smith, from Jim Brown to Colin Kaepernick. He happily pulls up two pictures from his cell phone: one of him with Martin Luther King Jr., another of him with Malcolm X.

He will fight all his good fights, for however long he can.

“I am not just at peace,” he said. “I am fulfilled.”