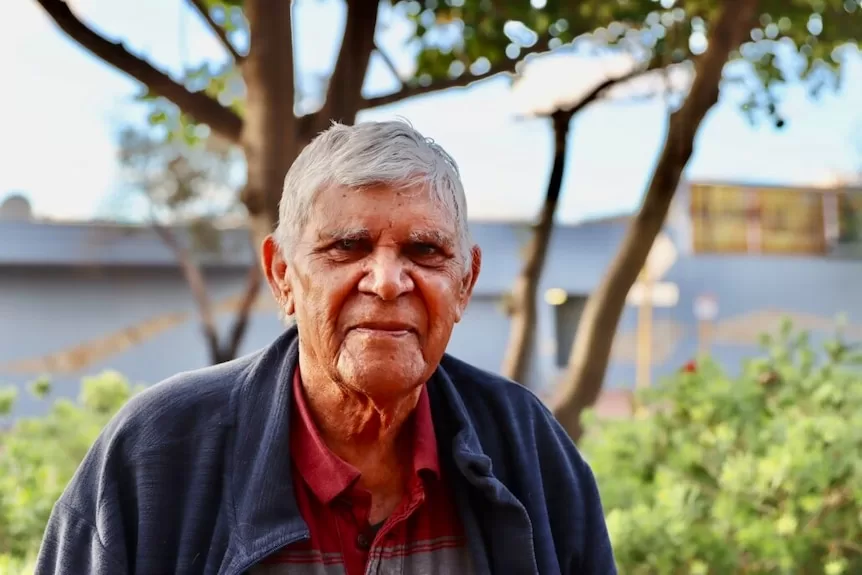

Aubrey Lynch, a Wongatha elder, remembers when he and his mother couldn’t get into Kalgoorlie’s town centre.

“If you were seen in town, you got put in jail.”

It was the 1940s, and Mr Lynch, who will turn 87 next month, was “only a kid running around” in Western Australia’s Goldfields.

He was too young to question the law, but old enough to recall how it made him feel.

“Angry, I suppose, but very frightened. During that time, you knew to keep out of the way of the authorities, otherwise you’d get locked up,” Mr Lynch said.

“You put up with the law at the time, we weren’t allowed to go there, and that’s all that mattered.”

A series of proclamations were passed in the 1930s to exclude Aboriginal people from entering towns and settlements unless they carried a permit, which was given to those who had a job in town.

Perth was the first place in WA to declare a prohibited area.

Kalgoorlie-Boulder followed suit in 1936 with a series of proclamations that prohibited Aboriginal people from being within 6 miles (or 9.6 kilometres) of the town centre.

“We’ve seen lots of Aboriginal people being locked up for not obeying the rules,” Mr Lynch said.

Legacy affecting Native Title rights

For Mr Lynch, not being able to enter town meant struggling to find safe accommodation.

For other Aboriginal people, prohibited areas limited access to water, healthcare, job opportunities and services, making it difficult for those whose children were removed due to the Stolen Generation policies to talk to government officials.

Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre chief executive Sue Hanson said the proclamations had been damaging for families.

“Imagine you are sitting on the outskirts of a town, and you are not permitted to go in and try to find your family members, it must have been quite a torment for people,” Sue Hanson said.

She said the proclamations, abolished 70 years ago, still affected people’s rights in Kalgoorlie-Boulder today.

Native title rights over the mining city have not yet been officially determined, with a number of conflicting claims over Kalgoorlie-Boulder and its surrounds.

“For about 20 years, there are no photos or documented evidence of Aboriginal people being in Kalgoorlie-Boulder,” Ms Hanson said.

“That’s impacting people who are trying to prove native title.”

Hidden history and a way forward

The language centre is currently staging an exhibition on the history of prohibited areas, the first in what Ms Hanson hopes will be a series on the Goldfields’ “hidden history”.

She says truth-telling can “bring Australia into a mature country”.

“It allows people to engage with history, and also look at the impact of history and be more understanding towards each other,” she said.

Rex Weldon, a Murri man from Queensland, moved to the Goldfields when he married a Wongatha woman, and worked as a police officer in Laverton for 21 years.

For him, learning is a step towards reconciliation.

“There’s no two-way about it, what we are all aiming for is equality,” Mr Weldon said.

In his time in the force, he worked to make relationships between Aboriginal people and the police better than what they used to be in the past.

“It’s an ongoing process and I think both sides have got to keep working on it,” he said.

Mr Lynch fought for Aboriginal rights and marched in Perth and Canberra.

Now he’s working with mining companies and other organisations to share struggles of the past to promote cultural awareness.

“It’s important to have respect from each side, the Aboriginal side and the non-Aboriginal side,” he said

“It’s the only way we can move along together.”