Diane Lynn sat in terror-stricken disbelief on the side of the pitch when a rival fan offered her a cup of tea.

On a famously sunny spring afternoon in 1989 Lynn, then 22, and her 17-year-old brother had been pulled from a crush of bodies at the Leppings Lane end of Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield.

The crush would ultimately result in the death of 97 of their fellow Liverpool fans.

Lynn and her brother had been in one of the two central pens where the tragedy unfolded.

“I knew I was dying,” Lynn says.

But she survived, climbing across into a different part of the Leppings Lane terrace in a blur, before finding herself on the pitch in front of the adjacent South Stand.

There, she flopped down in front of a section of Nottingham Forest supporters – fans, just like those of Liverpool, who had made the journey to South Yorkshire to watch their side in an FA Cup semi-final.

“We collapsed near Nottingham Forest fans and they were offering us cups of tea and coffee from their flasks,” Lynn tells BBC Sounds podcast Hillsborough Unheard: Nottingham Forest Fans.

“I’d love to know who they were. They kind of helped us; they calmed us down. My brother – I’ve never seen someone is such shock. He was so pale, he couldn’t speak and I still don’t know what he saw because we have never spoken about it.

“One of the Forest fans was a dad with a couple of kids – you think now, those poor, young kids, what they saw.”

None of the 28,000 Forest fans in attendance died that day, but Britain’s worst stadium disaster played out in front of them.

And, for many of the 35 years since, they have been Hillsborough’s silent witnesses.

Now, as vice-chair of the Hillsborough Survivors Support Alliance (HSA), Lynn has helped some Forest fans open up about what happened and come to terms with Hillsborough’s horrors.

“People in Liverpool need to hear what Nottingham Forest fans have got to say,” she says.

“They need to know exactly what happened to them, what they saw and that they were part of that tragedy.”

That is why, in 2021, she responded to a tweet from Forest, which marked the 32nd anniversary of the disaster, with a message of support for their fans who were there.

She signed off the HSA’s reply by writing, “we are here for everyone”.

Those five words meant so much to Forest fan Martin Peach.

“That was a huge moment,” he says.

“I just remember thinking, ‘wow, that is the first time I’ve seen acknowledgment that Forest fans may have been affected by what they saw that day’.

“It felt like a real relief to be recognised and the responses to that from Forest fans were quite overwhelming.”

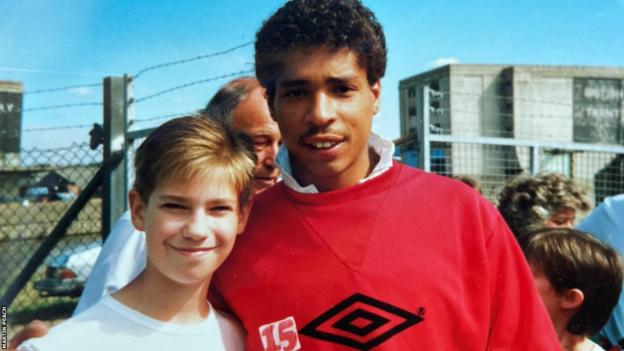

Peach was 12 years old in 1989 and sat in the South Stand, closer to the fenced Spion Kop end of Hillsborough – the behind-the-goal terrace where his fellow Forest supporters stood in their thousands, facing an unfolding disaster.

“I remember that day more vividly than any other day in my whole life, and I have thought about it every day for 35 years,” says Peach, who now has a 12-year-old daughter.

The image of police forming a cordon on the halfway line, and a Liverpool fan in ’80s rocker’ attire – long hair, beard, ripped jeans and leather jacket – barging through the line and running toward the Forest fans in despair, is among the scenes seared in his mind.

“He ran the whole length of the pitch and got to the goalmouth in front of the Kop, in front of 20,000 Forest fans, and he just dropped to his knees and was screaming his head off up to the heavens,” Peach recalls.

“That was the moment that Forest fans first thought, ‘There is something amiss here. This is not a pitch invasion. There is something seriously wrong’.

“It was a massive event that had a huge impact on me at a young age. There was never any outlet to talk about it or share it, so it has just stayed scarred into my brain.

“The match was on Saturday and on Monday I was back at school and got on with it. My parents must have asked if I was OK, but I don’t remember discussing it in much detail.”

Peach was a music-loving, football-mad child from Swanwick, a small village which falls on the Derbyshire side of the county border with Nottinghamshire.

He wasn’t the only youngster from the old mining community who went to the game. Two 18-year-old Liverpool fans from the area also made the journey.

“One of them came home and the other didn’t,” Peach says.

“That’s why Hillsborough has been a really important issue for me.

“I know how easily it could have been me who didn’t come home that day, if I’d chosen to support Liverpool instead of Forest, or we had been given opposite ends that day.”

For more than an hour, Peach was among the Forest fans who could do nothing but watch on.

At least one Forest fan sat by him attempted to get on to the pitch to help administer first aid, but police blocked their access.

In 2016 an inquest found that the 96 fans – which later became 97 – were unlawfully killed amid a number of police errors.

It took 27 years for that verdict to be passed down.

Survivors and families campaigned for three decades to discover what led to the deaths.

On the day itself, Forest fans, only 100 yards away at the opposite end of the pitch, struggled to fathom the gravity of the situation.

Peter Hillier, then a 25-year-old Forest fan, had taken the train from London to join his father and brother on Hillsborough’s Kop to support a team challenging for every major honour at home and abroad.

For more than a decade Forest had battled with Liverpool for some of the game’s biggest prizes.

The rivalry was intense and tensions between supporters were often high. Crowd trouble was common.

When Hillier first saw people in the Leppings Lane terrace trying to climb over the fences, he admits his “first suspicion” and the “assumption” of many at the Forest end was that it was an attempted pitch invasion.

“Those things happened in those days,” he says.

“And people hurled abuse. That changed when you could see people were desperate.

“The gates were then opened, and they started bringing people out and you had Liverpool supporters ripping up the advertising hoardings to carry what you assumed might be injured people away.”

A number of those people on makeshift stretchers were brought over and laid out in the penalty area in front of the Forest supporters.

“You realised these people weren’t injured with a broken leg. You could see people doing resuscitation and trying to save people. Then you would see them stop,” Hillier says.

“Somewhere along the line you realised someone has died there.

“It was numbing, because you couldn’t do anything. It was silent by then. There was no more chanting, no abuse. It was bewilderment.”

Hillier had his father and brother to talk to in the terrace, but they did not speak about what they saw then, nor in the years since.

“We stood there not wanting to be there,” he says.

“It is not a normal human experience to watch 97 people be killed.”

For years afterwards, Hillier says he had recurring nightmares, struggled to form relationships and grappled with alcohol issues.

He feels he reacted, like the vast majority of Forest fans, by bottling up the trauma.

“There was the feeling that it didn’t happen to us,” he says. “We were there, but it’s Liverpool’s tragedy and we are a by-product of it.”

The perception of Forest fans was damaged on Merseyside by what Brian Clough, Forest manager at the time, said about the catastrophe.

Clough, who had guided Forest to an English title and two European Cup triumphs, repeated infamous and inaccurate claims that Liverpool fans were to blame for what happened.

Clough later apologised for his comments before his death in 2004.

“It caused a lot of resentment and probably an assumption in Liverpool that everyone in Nottingham feels like that,” says Hillier.

“He was a hero, and is still my hero, and he made a mistake on that. If people delve into that, they will find that he was badly advised.

“He retracted it much, much later, and people in Liverpool will say too little, too late.”

Hillier and Peach were among the Forest supporters who produced a huge banner calling for an end to tragedy chants and respect for the 97 fans who lost their lives through the Hillsborough tragedy. It was first unfurled at Anfield in 2023.

Forest fan Amanda Stanger, who was in the South Stand at Hillsborough in 1989, says the memory of that day “never goes away”.

She now works in a prison and the sight of people behind fences has caused flashbacks. She has been stricken by panic attacks in crowds.

But she worries most about what some fellow supporters may chant whenever Forest play Liverpool – a fixture that has only become regular again in the past two seasons after her club ended their 23-year Premier League absence.

“My anxiety levels go through the roof,” she says.

“I wonder, what will I do? What will I say? I can’t ignore it.

“We’ve had that only recently, but Liverpool supporters have that every single match, no matter who they play.”

Stanger was once invited by an anti-discrimination charity, Kick it Out, to meet with a Forest fan who had been found to be tragedy chanting.

“The shock was that his dad was at Hillsborough,” Stanger says.

“I asked him, ‘why did you do it and how is your dad?’ He thought his dad was fine about Hillsborough because he didn’t speak about it, but that tells me loads. That tells me he doesn’t speak about it because emotionally he probably can’t speak about it, not because he doesn’t want to speak about it.”

Stanger has found comfort in recent years by talking about her experiences.

She took up the offer of therapy that the HSA funds, and has since set up a Nottingham branch of the alliance.

On her first trip to Anfield to attend a HSA meeting she says she was “petrified”. Afterwards it was as if she had “found a new family”.

“When I sat there and was asked to introduce myself, I got emotional,” she says.

“I said, ‘I’m Amanda and I’m a Forest supporter and was at Hillsborough’. And one person turned to me and said, ‘you are a survivor – you are one of us’.

“Nobody had ever said that. You don’t think of yourself as a survivor – you think of yourself as a Forest supporter who was there and nothing more than that.”

Whenever she is at Liverpool’s home ground, she visits the eternal flame memorial to think about all of those who lost their lives.

Stood in front of that tribute, she shed a tear explaining what it would mean to have something at Forest’s City Ground to remember a tragedy that has linked the Reds from the banks of the River Trent to the Reds from Merseyside.

“This is what we need at Forest, just somewhere to go and have a cry and to say we are sorry – sorry because it should never have happened,” Stanger says.