Desperate for some communication from her three abducted children, Izumi quickly opened an envelope that had arrived in the mail.

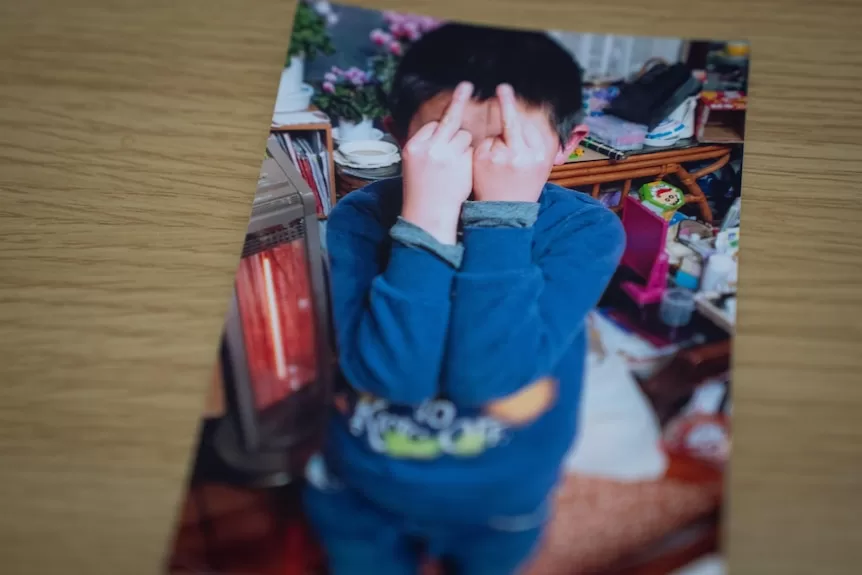

Inside were a series of photos that left her stunned.

One image showed her daughter holding a sign that said “die old bitch”.

Her son was next to her, holding another piece of paper that said “stupid shit”.

Other photos were just as heartbreaking.

Her daughter was shown using scissors to cut up Izumi’s handcrafted letters. Her son was giving Izumi the middle finger.

“They weren’t children who would do such things,” she told 7.30.

“I imagined they were being forced to do these things and having a hard time.”

It’s been seven years since Izumi last saw her two daughters and son.

Fed up with her husband’s behaviour, accusing him of affairs and physical abuse, she fled the marriage with her children.

But in the months that followed they were taken back from her, one-by-one, never to be seen again.

She continues to fight for visitation and access, but it’s proving to be an impossible dream.

In Japan, courts only grant one parent full control during a custody dispute.

Custody is typically granted to the parent who has physical possession of the children. It’s supposed to provide stability, but critics say it incentivises child abduction.

The issue is not just one for Japanese parents.

There have been 89 Australian children reported as victims of parental abduction in Japan since 2004 and in the past 12 months alone DFAT says seven were added to that tally.

“The one who takes the child wins,” Izumi told 7.30.

“The police said at the time, ‘There’s no problem as it’s the father that took the children.’ They said it’s a family matter and didn’t do anything to help see my children.

“The courts don’t understand how people feel or how children feel.”

The photos Izumi received were supposed to provide some comfort early into her drawn-out battle. They were supposed to confirm the welfare of the children.

Instead, she received abuse and the courts did nothing to intervene.

“I didn’t do anything bad and I care for them deeply, but I can’t see them,” she said, tearfully.

“Why can’t I see them?”

Japan set to change custody laws

After years of increasing pressure, the Japanese government has finally decided to change its sole custody laws, giving courts the power to enforce joint custody if there is a dispute.

Legislation was introduced to parliament in March and is expected to pass both houses by mid-year.

But rather than settle the long-running dispute, the laws have only deepened division in an already bitter, emotional debate.

Parents who have lost their children say the laws don’t go far enough, while victims of family violence are demanding they are scrapped.

Family law expert, Emeritus Professor Shuhei Ninomiya from Ritsumeikan University, said Japan’s joint custody legislation is a step in the right direction.

“Seventy per cent of children do not see their separated non-custodial parent after divorce,” he said.

“Seventy per cent are also not receiving child support. I think this reality needs to be changed in some way. In order to change that, we need to make joint custody.”

The laws were created after a year-long review process which attracted a wide range of submissions, including one from the Australian government promoting joint custody.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of a Child, which Japan is a signatory to, states children should have access to both parents when it is safe to do so.

The new laws are seen as a way for Japan to become more in line with comparable countries.

But Professor Ninomiya sees shortfalls in the current legislation.

Visitation rights are not guaranteed, meaning parents could still go many years without seeing their kids, while the legal dispute is ongoing.

This meant children could be “brainwashed” into hating their separated parent, also known as parental alienation.

“The biggest solution to prevent this is to continue trial visitation until a conclusion is reached,” he said.

‘Insufficient screening for family violence’

Survivors of family violence have been some of the biggest critics of joint custody, calling for the proposed laws to be scrapped.

Their fear is joint custody will force victims back into the orbit of an abusive partner.

“There is only one policy, which is the victim runs away,” said Chisato Kitanaka, head of Women’s Shelters Network Japan.

“Only in very severe cases does the court issue a restraining order. There is basically no punishment for the perpetrators. Domestic violence courts are not functioning.”

Mother of two boys Hiromi Tomoyama is one of those voices, joining about 100 other protesters this week outside parliament.

She says she left her relationship after 15 years of financial and physical abuse.

“It’s about being forced,” she said.

“I’ve been forced to do everything and then been deprived of everything.

“I feel very sorry for the children. Everything in our lives was gone, we had no water, we had no gas.”

Japan’s latest survey on family violence showed almost one in five people had experienced family violence, an increase of almost six per cent since the 2020 survey.

Women are disproportionately affected, with almost 23 per cent of women reporting abuse, compared to 12 per cent of men.

Hiromi has documented her allegations of physical abuse, including photos of bruising and medical reports.

Her ex-partner denies the claim.

“I haven’t been paid child support for three years now, and I’m living in poverty as a single mother,” she said.

“We first need a system that supports parents and children that were hurt.

“There is no organisation to certify domestic violence. Can [judges] really make the right decisions? I’m really anxious.”

Izumi also submitted photos showing bruising to the courts in the early days of her custody battle. It didn’t help her case.

“It’s not a society where adults protect children properly,” she said.

Professor Ninomiya agrees Japan’s family legal system is poorly equipped to deal with family violence.

“There is insufficient screening for domestic violence,” he said.

“Investigators do not have specialist skills in domestic violence.”

‘I don’t know what the kids look like’

Those who have lost access to their child argue they too are suffering a form of family violence.

Australian dad Scott McIntyre returned to his Tokyo home five years ago to find his wife had taken their two Australian-born children.

His story attracted international headlines in 2020 after he was arrested for trespassing and jailed for six-weeks.

At the time, Scott was trying to confirm the welfare of his abducted Australian children, so he went to the public area of his in-law’s apartment.

Since then he has received no scraps of information, despite pleading his case to the courts and submitting evidence that included a 30-page report from a child psychologist.

He’s pressured the Australian government to locate his kids.

He even got an Interpol notice issued on his children, which lists them as being abducted by a parent.

“I don’t know what the kids look like,” he said.

“I don’t know if they’re in Japan. I don’t know where they are. I don’t know if they’re dead.”

It’s led him to conclude the judiciary is not only ill-equipped, but also disinterested, in handling child custody disputes with thoughtful consideration.

“It’s been this way for 50 years,” he said.

“The courts won’t change. And the judges won’t change.

“What I want to happen is an independent panel of experts [and] they make a thorough and rapid investigation.”

‘I love you no matter what’

Those fighting for access to their own children feel they are being punished for the crimes of the minority.

Most divorcees do not claim family violence as the reason for a break-up – only about 3 or 4 per cent, according to Professor Ninomiya.

It’s for this reason he wants joint custody laws to press ahead, while still acknowledging further improvements must be made.

“I think it’s necessary to introduce a joint custody system, even if it is selective, in order to guarantee the rights of many children,” he said.

Parents simply do not want to wait any longer.

They have already missed too many major milestones, and the years continue to tick by.

Izumi, who holds little hope she’ll see her kids again, has one final plea.

“I want to tell them that we haven’t seen each other for a long time now, but I love you no matter what,” she said.

Watch 7.30, Mondays to Thursdays 7:30pm on ABC iview and ABC TV