An unapologetic confession or perhaps a warning comes a few pages inside: “I’m a liar. I’m a thief. I’m emotionally shallow,” Gagne writes. “I’m mostly immune to remorse and guilt. I’m highly manipulative. I don’t care what other people think. I’m not interested in morals. I’m not interested, period. Rules do not factor into my decision making. I’m capable of almost anything.”

That bold declaration leads one to wonder about the veracity of a memoir written by a confessed, if charming, part-time fabulist: “I’m not a perfect messenger,” Gagne said during a Zoom conversation while sitting in front of a bookcase in a house in a city she asked not to be identified over concerns that others with mental disorders might contact her. “I know my stories are true, but I also know not everyone is going to believe them.”

Gagne’s tale is a map of psychological discovery and illicit tendencies. Published by Simon & Schuster, the new memoir traces the life of a girl who grew into a woman trying to understand her sociopathy, which today is often labeled as antisocial personality disorder. Gagne knew early that she was different, fighting an apathy that could spark an anxiousness that provoked destructive outbursts. She mimicked the emotions she lacked to fit into a world where novels and films tended to depict sociopaths as violent and soulless transgressors treading the fringes.

“Lying kept me safe. I was sliding under the radar,” Gagne, 48, said in the interview, estimating that as many as 15 million Americans may be sociopaths. (In an overview of Antisocial Personality Disorder, the Cleveland Clinic states that it “affects an estimated 1% to 4% of adults in the U.S.”; 4% of the current population is about 13.7 million Americans.)

“There’s nothing inherently immoral about having limited access to your emotions,” Gagne added. “Not all sociopaths are dangerous criminals. They’re not going to be easy to spot. They’re not going to be stereotypical monsters. You could be sleeping next to one. You could have, in fact, birthed one.”

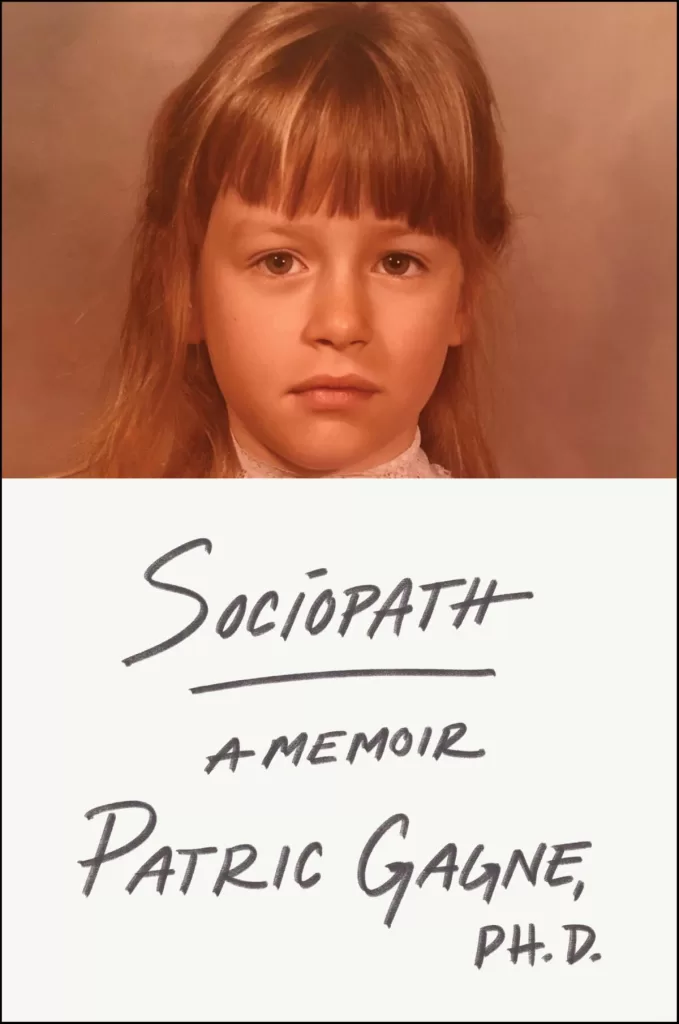

(Stephen Holvik / Simon & Schuster)

A master of interior disguise, Gagne is married with two children and has settled into a well-to-do conformity. She is a former therapist with a doctorate in clinical psychology. Her years-long mission has been to, as she puts it, demystify and humanize a condition that has been “misappropriated to cover all manner of sin.” She has learned to navigate the contours of love, empathy and other feelings even as in her younger days she felt the “cunning genius of [a] subconscious mind” — like a jazz composition of loose rules and shifting structures. She became less interloper than practiced assimilator.

“I find neurotypical people fascinating. You guys are like ice skaters. All of these colorful emotions,” said Gagne. “These little things you do. I could watch it all day. I don’t want to be an ice skater, but I really find it fascinating. In much the same way that neurotypical people find me fascinating. I’m not envious of it. But you guys have more pieces on the chess board than I do.”

Gagne said she is grateful not to possess some of those pieces, notably guilt and shame, which she sees in her Catholic-raised husband. “It seems,” she said, “like a very heavy and unnecessary burden.”

But she can telegraph moods. In 2011, when she was working as a therapist, she wrote and acted in a skit for the Groundlings comedy troupe. It was titled “Resting Bitch Face,” a phrase her sister whispered to her in high school whenever Gagne’s face slipped into a sociopathic gaze. That inspired the sketch about a hiring interviewer whose alternating expressions of smiles and scowls unnerve a job candidate played by Nate Clark.

“I enjoyed working with her, but I wouldn’t characterize Patric as the warmest person,” said Clark, a writer and independent creative director, adding that Gagne was open about her sociopathy. “The ‘Resting Bitch Face’ sketch came from her personal experience. That makes good comedy. Her writing was always very self aware. She had intelligence and a lot of different experiences. I don’t think she cared what people thought of her. She had a unique point of view.”

The daughter of a music industry executive, Gagne lived in Florida before moving to Los Angeles to attend UCLA. Her impulses flared. She’d break into a house and sit in the quiet — stealing nothing — and then vanish into the night, her apathy jolted by an unlawful act that would calm her brain. She stole cars, joy riding for hours and later returning the vehicle, sometimes putting gas in the tank, a consideration she called a “karmic adjustment.” It was, in her telling, the thrill she craved, which was easily found in a city accustomed to reinvention and experimentation.

“In L.A., you can be anybody you want,” she said, remembering how people responded when she told them she was a sociopath: “They’d say, ‘Tell me more. Oh, let me hear about that.’ Everyone in Los Angeles, I think, has a streak of darkness. Certainly, that can be used negatively but also positively. Anyone and everyone who is a ‘misfit’ can find their place in Los Angeles. That was really true for me.”

She attended classes at UCLA — later earning a PhD from the California Graduate Institute of the Chicago School of Professional Psychology — and after graduation worked as a talent manager for her father’s company. The memoir offers an evocative glimpse of the music business, but, like much of the book, relies on pseudonyms, composite characters and long stretches of reconstructed conversations. The prose moves and the dialogue is sharp, but as in the case with Max, a star musician whose real identity is withheld, Gagne expects more than a degree of trust from the reader.

Kirkus Reviews noted that “the narrative itself, which relies heavily on conventions from the romance and thriller genres, has a markedly fantastical quality, and what emerges often seems to favor vivid storytelling and self-aggrandizement over honest introspection. . . Though the book is marketed as a memoir, it reads very much like a work of fiction.”

Gagne said her intent was to protect the privacy of characters by not naming them, noting the flashes of criminality described in her story. “I’ve lived a very colorful life, and in the editing process, the more colorful stories rose to the surface,” she said, adding that the original manuscript was about 200,000 words. “I can understand how someone reading this might have that opinion where this just seems to fit together too perfectly.”

Publishers Weekly commended Gagne’s honesty and introspection. It praised the memoir as “courageously candid and sometimes shocking,” calling it a “no-holds-barred self-portrait [that] offers an illuminating glimpse at a mental health disorder long shrouded by shame.”

The book is most insightful when Gagne struggles to clinically define herself and how to relate to emotions she didn’t have or could only interpret or approximate. Her frustration is enveloping but she is a tireless investigator. She consulted psychology textbooks, journal articles and other research, including conversations with therapists and professors, but for years her essence appeared elusive. She writes: “While I could easily identify with most of the traits on the sociopathic and psychopathic checklists, I was only able to relate to about half of the antisocial ones.”

Unlike a psychopath, Gagne did not have brain abnormalities. With the help of counseling, she realized she was a sociopath, although she notes that there is not a “singular definition” for the term. She believed that most people like her could learn to control their impulses. In an interview, she said that early on she discovered how to repress violent urges, knowing that if she didn’t she would be outed as different and become a “walking red flag.” Today, she said, she has no desire to hurt people but must reign in other compulsions.

“It’s my internal philosophy,” she said. “If you act out, your family, husband, that part of your life will suffer but the sociopathic side that gets off on these things will benefit. Which one do you want to pick? Nine times out of 10, as much as I would like to get away with these occasional destructive acts, I will choose this life I have chosen to lead. You have to make sacrifices.”

Much of the story tracks the often tempestuous relationship with her husband, David, a technology consultant. They met when she was a girl at summer camp and reconnected years later in Los Angeles. His was an enduring love, even as revelations about her disorder, including urges to break into houses, multiplied. “Why do you have a lock-picking kit?” he once asked her. David often felt irrelevant — that he cared about the relationship and she didn’t — and wanted things she could not give. Over time, and, again, through counseling, she said, their bond deepened and they had two children.

“David’s ability to accept my sociopathic symptoms,” she writes, “was nothing short of life-changing for me.”

But Gagne said her emotional detachment can complicate family life. It can also provide clarity and not letting feelings get in the way of solving problems. When asked if her children — boys ages 8 and 13 — sometimes hoped for more emotion from her, she said: “They probably do. But I have worked really hard to give them the space to tell me things. Sometimes they say, ‘Mommy, I want X,Y and Z from you. Can you try and give me that?’ and I try.”

Gagne writes in the memoir that when her first son was born, “I was not overcome with emotion. I didn’t get the profound surge of ‘perfect’ love I’d been promised. … I was unable to connect with my feelings — I was furious.” She later writes that she told her child: “‘You have a weirdo for a mom, babe,’ I said to him. ‘So I can’t promise your childhood is going to be entirely normal. … But I can promise that I will never put you in danger. You will never be safer than you are when you’re with me.’”

It is not always easy. Life, with all its calibrations, turns on unpredictable things. Gagne’s X bio is at once matter-of-fact and slightly fantastical: “David’s wife. Mother of dragons. Writer. Doctor. Sociopath.” She said she has come far from the 9-year-old with uneven bangs on the book’s cover, the one who secretly stole a barrette from a friend’s hair, was once transfixed by Blondie, and would later quote Oscar Wilde — “Every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future.”

But she still relates to that long-ago child: “I see myself in her. I know that stare. I know what you’re thinking, kid. I gotcha,” she said. “I’m also filled with compassion for her. … No one empathizes with a kid who doesn’t experience the social emotions. Nobody empathizes with the sociopath. I had to use my own sociopathic experience, my own lack of that empathetic experience, in order to create it. No one is empathizing with me. However, I can empathize with that little kid.”