“At just over 10 pounds, I wasn’t earning enough. Everything from energy to food prices and rent have gone up in recent years,” Subramanian told Al Jazeera.

While the new legal minimum wage, also known as the National Living Wage (NLW), represents a 9.8 percent increase from previous levels – the highest single boost since 2001 – it is still insufficient for Subramanian. “All my charges have increased since COVID,” she said.

The boost to the NLW, worth 1,800 pounds ($2,271) a year for full-time workers, will benefit 2.7 million people, according to an estimate from the Department for Business and Trade.

The move is part of a 2019 Conservative Party pledge to raise the NLW to two-thirds of average earnings. In 2022, the OECD estimated that the UK’s minimum wage was equivalent to 58 percent of the median wage.

The Conservatives, who have been in power since 2010, rebranded the statutory minimum wage as the NLW in 2015. Initially, it only applied to Britons over the age of 25. Since then, the age limit for those earning the NLW was lowered to 23.

Now, eligibility will be extended to 21-year-olds. Minimum wage rates for younger workers will also increase, with those aged between 18-20 receiving an uplift of 1.11 pounds ($1.40) an hour. For those aged 16-17, pay will rise by 1.12 ($1.41).

The independent Low Pay Commission – a body set up to advise ministers on the minimum wage – produces NLW recommendations every year. This hike represents an acceptance, in full, of last year’s proposal.

Speaking last November, the UK’s Treasury Secretary Jeremy Hunt said that today’s wage boost “will end low-pay in this country,” and that, “the national living wage has helped halve the number of people on low pay since 2010, making sure work always pays.”

The move has been welcomed by trade unions. But many feel the NLW needs to rise by more to keep up with inflation.

Afzal Rahman, a policy officer for the Trade Union Congress told Al Jazeera, “Don’t get me wrong, today’s move was badly needed.”

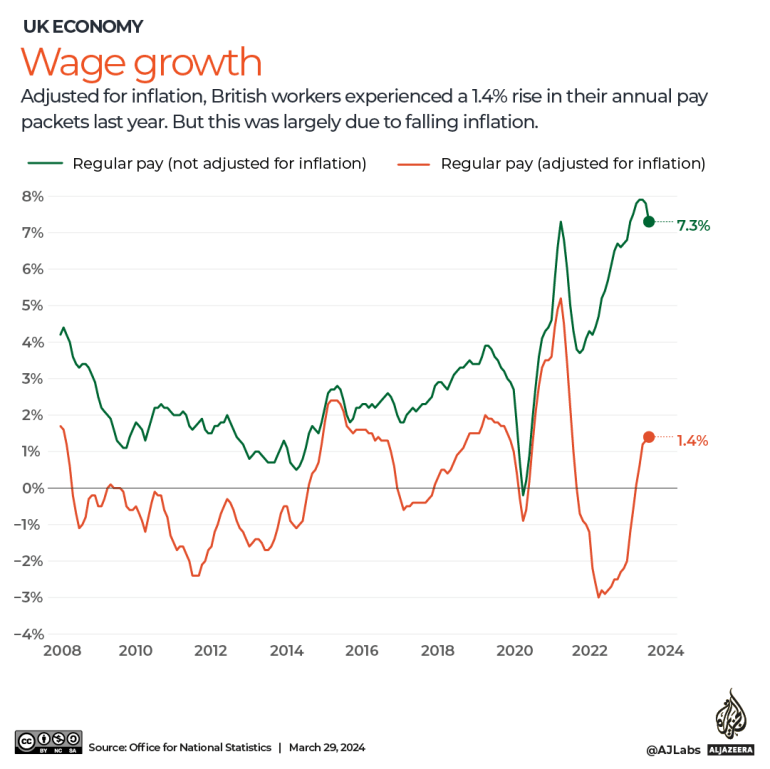

“But we can’t lose sight of the bigger picture. We’re calling for a minimum wage of 15 pounds ($18.93) as soon as possible,” he said, stressing that average pay packets have flatlined in real terms over the past 15 years by failing to keep up with consumer prices.

Central bank considerations

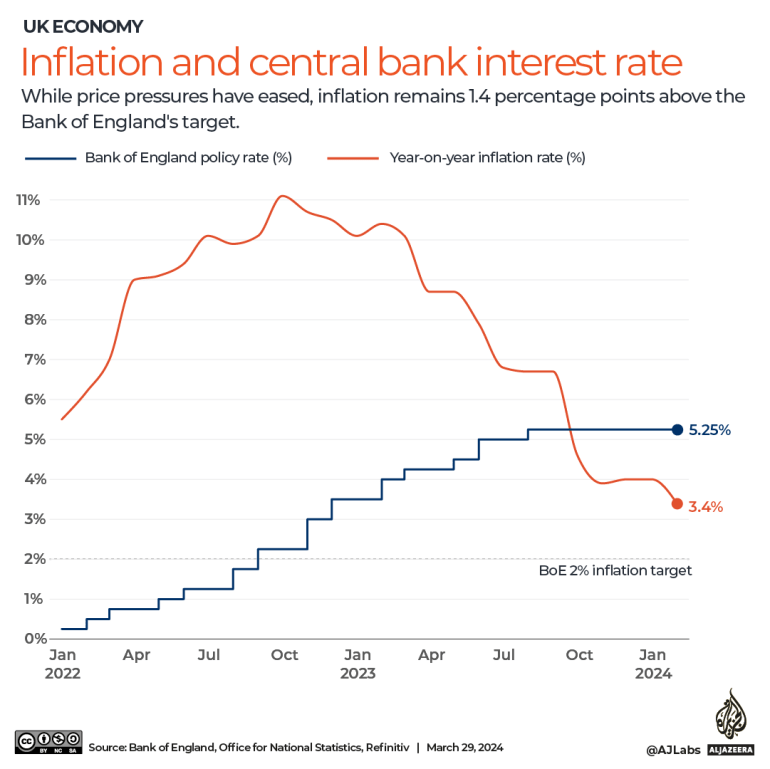

Last year, real wage growth was high by historical standards. Adjusted for inflation, British workers experienced a 1.4 percent rise in their annual pay packets. But this was largely due to falling inflation. Consumer prices fell from a peak of 11.1 percent in October 2022 to 3.4 percent this February, owing mainly to declining energy prices. In addition, the Bank of England’s (BoE) monetary tightening campaign has let steam out of the economy.

And while price pressures have eased, inflation remains 1.4 percentage points above the BoE’s target of 2 percent. In turn, the new NLW will keep policymakers on their toes for signs that pay growth could feed a new round of inflation.

“Central bank officials are concerned that raising the NLW could have knock-on effects, as employers seek to compensate staff higher up their pay scales,” said Edward Allenby, a UK analyst at Oxford Economics.

“Still, the latest trends in inflation have been positive. And while the BoE will be monitoring price effects from the new minimum wage, we think that overall inflation will continue to fall,” he said.

Allenby also noted that just 5 percent of the UK’s workforce was paid the NLW in 2023. “Taking everything into account, we expect the BoE to press ahead with lower interest rates this summer despite the higher wage floor,” he said.

Real living wage

Distinct from the NLW is the real living wage. Set by the Living Wage Foundation, a charity, at 12 pounds ($15.14) per hour nationally and 13.15 pounds ($16.59) in London, the real living wage is indexed to living expenses. Employers can choose to pay it on a voluntary basis.

In total, 14,000 employers are committed to paying the real living wage. According to Gail Irvine, a policy manager at the Living Wage Foundation, that means there are 3.7 million people – or 13 percent of the UK’s total workforce – paid below 12 pounds per hour.

“The real living wage is about trying to create a fairer society. In Britain, we’ve got a long way to go,” she said. The UK’s Gini coefficient, which measures wage inequality, tallies at 35, near its 2007 peak, higher than any EU country except Latvia and Lithuania.

A Gini score of zero would represent total equality, where income is shared evenly among all households. The higher the score, the greater the income inequality. For context, the UK’s Gini coefficient was 25.3 in 1979.

Away from headline measures, the Equality Trust, a charity, estimated that the top 10 percent of UK earners saw their share of national income rise by 23 percent from 1980-2020. Over the same period, the UK’s total income allocated to the bottom 50 percent fell by 7 percent.

At the highest end of the income spectrum, chief executive pay for FTSE 100 companies, the largest firms on the London Stock Exchange, was 130 times that of their average employee in 2020.

“Clearly, the benefits of national income growth have disproportionately benefitted high earners in recent decades,” said Irvine. “And that’s a big problem, because as most people’s real wages have stagnated or fallen, house prices have gone up.”

She pointed out that, “incomes have risen slower than rent and mortgages for most people, who have to spend more and more on accommodation. The new NLW is welcome, but the lift is too low relative to wider cost pressures, and especially since COVID.”

Last month, Treasury Secretary Hunt hinted that the UK’s next general election will be held in October. Conservatives are currently trailing the opposition Labour Party by 27 percentage points.

Keerthi, the South London shop assistant, will wait to see how the new minimum wage affects her lifestyle before the elections. “If the Conservatives can’t bring down costs, especially rent, I think they’ll be in trouble.”