The property, at 1100 Kettner Blvd., two blocks from the piers at San Diego Bay, consists of two structures, which opened to the art public in 2007. Exhibitions were held in the historic Santa Fe railroad baggage depot, built for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition and now named for museum benefactors Irwin Jacobs, billionaire co-founder of Qualcomm, and his wife, Joan. Like an adjacent office and storage building, named for the late newspaper publisher and museum trustee David C. Copley, the baggage depot was shuttered during the COVID-19 pandemic and did not reopen.

The sale of the downtown facility will dramatically alter perceptions of the museum’s long-standing binational mandate, aimed at artists and audiences in the border area of San Diego and Tijuana. Closure also raises difficult questions about the fate of several works of art in the permanent collection. Sculptures and installations by Robert Irwin, Richard Serra, Maya Lin and three other artists were commissioned expressly for the site.

Two sources with direct knowledge of the liquidation plan and who requested anonymity to speak freely said the museum was facing a sizable operating deficit. However, museum Director Kathryn Kanjo denied the claim in an interview. “We’re not running a deficit this year,” she said. MCASD operates on a fiscal rather than calendar year, from July through June.

(Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego)

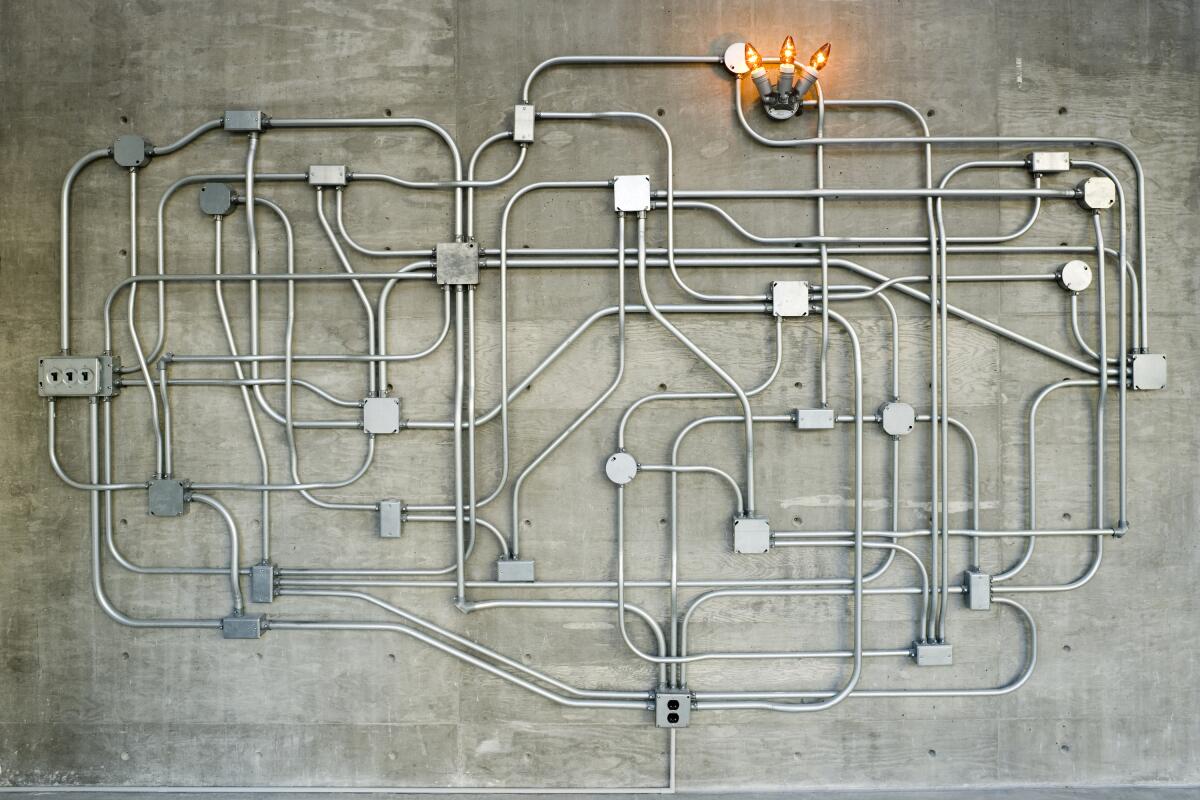

Installed in designated locations around the complex, the art will not be sold with the buildings, Kanjo said. Some artists might be asked to relocate their works. Jenny Holzer’s “For MCASD” (2007), a 61-foot-tall LED-sign attached to the Copley facade, and “Power Maze With Sconce” (1998), an elaborate indoor lighting fixture by Roman de Salvo, are candidates for possible transfer to La Jolla.

Others, including a massive Serra steel sculpture weighing more than 300,000 pounds, cannot be moved. How the buildings will be sold while the art remains in the museum’s possession “remains to be seen,” Kanjo said.

The decision to sell the property represents a significant challenge to the museum’s long-standing commitment to binational culture in the nation’s eighth largest city. Border art activities generated by artists in the 1980s brought the region its first sustained cultural notoriety on a larger-than-local scale. In a late February memo to museum staff obtained by The Times, Kanjo described the closure as an effort to concentrate programming in La Jolla, 13 miles up the coast, after its recent enlargement.

The director noted that gallery space at the La Jolla museum had quadrupled and that visitor amenities had expanded. “These successes,” she wrote, “coupled with the ongoing financial impact of operating multiple gallery spaces, have prompted the Board to take the significant step of listing 1100 Kettner Blvd. for sale or lease.”

The 18,000-square-foot Jacobs building is being marketed as a retail storefront for $3.65 million. The three-story Copley building is going for $2.65 million. The pair is listed at $6,299,400. David Marino, an executive at commercial real estate firm Hughes Marino and a MCASD trustee, is handling the transaction on a pro bono basis, according to the sources, to avoid a potential conflict of interest. Marino did not respond to a request for comment.

Roman de Salvo, “Power Maze with Sconce,” 1998, mixed media.

(Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego)

The plan to sell the facilities follows the March 5 transfer of a third building. A leased downtown space across the street at One America Plaza, an office tower owned by the Irvine Co., began to host MCASD art exhibitions more than 30 years ago. (The museum had nearly 70 years left on its $1-a-year lease.) More recently, the building has been home to the museum’s education department.

The One America Plaza facility features 10,000 square feet of interior space designed by Irwin, environmental artist Richard Fleischner and architect David Raphael Singer. It is slated to become the second home of the Navy SEAL Museum, based in Fort Pierce, Fla., and scheduled to open in December. Close to 90,000 active and retired Navy personnel live in San Diego County.

The art museum’s mandate, formally adopted in 1998 and declared on its website, is to engage “regional, national, and international audiences including the binational constituency of the San Diego/Tijuana region.” The San Diego Trolley runs between One American Plaza and the border crossing at San Ysidro, the busiest in the Western Hemisphere.

The Jacobs building had been a centerpiece for many of the museum’s Latino initiatives. The final exhibition before the pandemic was a retrospective of the late Chicana feminist artist Yolanda López, who was raised in San Diego’s Barrio Logan neighborhood. Mass transit from the city center to La Jolla is limited to bus lines, extending the 30-minute travel time from the border to museum programs to at least 90 minutes on multiple carriers.

The six commissioned works of art at the downtown site present thorny issues. They will be “carved out from the sale of the building,” Kanjo said, although exactly how they will function as protected museum objects available to the public is as yet unknown. Most cannot be moved without destroying them.

Irwin’s brilliant “Light and Space” (2007) is a mammoth installation of 115 fluorescent lights, created for a specific interior wall that is more than 22 feet high and 51 feet wide. An artist of international renown who called San Diego home for decades (he died in October at age 95), Irwin developed his installations in concert with the physical characteristics of the intended location.

Serra’s “Santa Fe Depot” (2004), an extraordinary sculptural ensemble arranged on the railroad loading platform behind the building and framed by the arcade’s arches, consists of six solid cubic blocks of forged, weatherproof steel, weighing in at a staggering 156 tons. The blocks each measure 52 by 58 by 64 inches, and they alternate along a center line — three on the left and three on the right. The six rest on different faces. The slight variations in scale yield an uncanny visual sense of tumbling lightness for these massive, immovable objects.

Lin’s delicate “Depot River” (2008) follows a meandering 25-foot crack in the building’s floor, a common construction blemish in large expanses of poured concrete. Lin filled the crack with silver leaf, playing on the traditional Japanese art of kintsugi, which repairs broken pottery with seams of silver, gold or platinum. The precious metal, emphasizing the breaks and flaws, dignifies age, usefulness and mortality. The jagged silver line of “Depot River” also evokes the omnipresent threat of the region’s earthquake faults.

An untitled 2006 work by Scottish artist Richard Wright is a secular re-imagining of an ecclesiastical rose window. The artist decorated the rippling glass of a high, arched window between two galleries in the Jacobs building with nearly imperceptible webs of shimmering gold leaf, which reflects the light passing through. Accentuating the glass wrinkles with gilding serves to sanctify the century-old depot structure.

MCASD’s Kanjo said that although the property is being marketed as retail space, the title stipulates that the new owner — or tenant, if a lease is arranged — of the downtown facility is restricted to cultural uses. Performing arts programs, art exhibitions or artists’ studios are among the possibilities, she said.

The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego opened its La Jolla flagship location in 2022 after a four-year, $110-million expansion.

(Maha Bazzari)

Whether or not MCASD is facing a deficit, perhaps related to closure during the pandemic, financial considerations surely have driven the lamentable decision to leave downtown. The museum still owes $3 million on the purchase of the Kettner Boulevard complex. Servicing that debt is accompanied by costs of staff, programs, insurance, utilities, maintenance and more. Operating expenses that grew significantly with the La Jolla expansion may have eaten up the downtown budget.

The knowledgeable sources indicate that on top of the funds raised for the La Jolla project, $20 million was expected to be added to the museum’s endowment, but that didn’t happen. Unexpected construction costs thwarted the plan. MCASD’s endowment is just over $44 million, relatively modest given the affluence of the La Jolla area. But a 5% annual draw on endowment covers 20% of the institution’s current operating budget of between $11 million and $12 million — a comparatively healthy percentage.

Ironically, in crass market terms, the art downtown may be collectively more valuable than the real estate being sold. Whether it is or not, however, questions of its future public accessibility and care now loom. The unresolved dilemma is unsettling.