The catch-all term encompasses your favorite rides, yes, but also an assortment of industries, ranging from architecture to animation to cinema to engineering to writing to game design. And that’s just a surface-level scan. Walt Disney Imagineering, the company’s secretive arm devoted to theme park experiences, likes to say that there are more than 100 job classifications among its ranks.

The theme park industry is also stealthy, a world of heavily trained spokespeople and nondisclosure agreements.

But once a year the Themed Entertainment Assn. throws an event in Southern California designed to honor the best of the past year. Honorees can range from the high-profile — the dance-like movements of Walt Disney World coaster Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind — to important but lesser known museum or new media offerings, such as Colored: The Unknown Life of Claudette Colvin, a traveling experience that arms attendees with augmented reality goggles and a small backpack, and sets them free to discover a forgotten story from the civil rights movement.

Accompanying the awards show are two days of panels and talks designed to give honorees the opportunity to discuss their projects. It provides a peek into the global theme park industry, and a high-level look at where the industry is heading.

I spent two days taking in these events in Hollywood, and this is what I learned.

(Eatrenalin)

Themed restaurants are becoming more interactive

Themed restaurants have come in and out of favor over the centuries — see the fanciful European-inspired façades and interiors of the World’s Fair restaurants of the 1890s, or the theatrical restaurant culture of Paris in the 18th and 19th centuries. Our city, of course, has had a rich history of themed restaurants, eateries decorated like a prison in the 1920s and a submarine in the late 1980s.

Germany’s Eatrenalin aims to go one step further, merging the techniques of a slow-moving dark ride with fine dining. Eatrenalin first started generating headlines in the themed entertainment space a little more than a year ago, and to combat any notion that it may be a gimmick, founders have long touted that it’s dedicated to exploring a multi-sensory experience. Each of its eight courses is served in a different room, but guests never have to leave their seats, as their chair will bring them from space to space by gliding across the trackless floor (think any number of modern rides, such as Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance at Disneyland, but slower, of course).

Expansive screens surround the diners — an underwater scene of colorful jellyfish accompanies a seafood pairing. But the backdrops aim to be more than a pretty setting; there’s a story to tell. Eat something sweet, for instance, and perhaps honey will appear on the screens as its scent slowly fills the room.

In an area dedicated to what co-founder Thomas Mack described as the “world of umami,” chairs will twist and glide guests into a space outfitted like a Japanese market. Think of each course as being served in a restaurant of its own, with the experience — starting at around $250 or so — ultimately taking guests to the moon.

Each course at Eatrenalin is served in a different room, which guests are ushered into via moving chairs. This publicity photo shows a space inspired by a Japanese market.

(Gerald Schilling / Eatrenalin)

Co-founder Oliver Altherr said the initial concept was born out of conversations about our increasingly tech-driven society and what it’s doing to attention spans. Eatrenalin wants to slow us down — smartphones are asked not to be used in most rooms, in part to keep guests focused on the story but also to preserve the experience for those who have not yet done it.

“When we looked at the trends at what’s happening in the world,” said Altherr, “we saw that the concentration space is getting shorter and shorter. People don’t want to sit the whole evening in a fine dining constellation in the same spot. They want more interactive stimulus.”

It appears to be working, so much so that Mack and Altherr were using their time in the United States to take meetings with investors for the second Eatrenalin location. So how about, say, Southern California, the birthplace of American make-believe and the modern theme park? “That’s one of the reasons we’re here now,” Altherr said, referring to their attendance at the Hollywood event. “We’re talking to people. We see L.A. or Las Vegas as a very nice spot for an Eatrenalin.”

Mario Kart: Bowser’s Challenge is an augmented reality-enhanced attraction, a tech some theme park execs will be a “disruption.”

(Universal Studios Hollywood)

Will augmented reality become more real?

Last year, the first major augmented reality attraction landed in the United States in the form of Mario Kart: Bowser’s Challenge at Universal Studios Hollywood. It’s a ride that places interactivity and playfulness ahead of speed and thrills. I’d argue it’s the best implementation of a game-focused attraction in Southern California, as it mixes silliness — the augmented reality comes courtesy of visors we wear, which also serve as aiming devices — with game-like proficiency amid largely physical sets.

But as much as I consider it a joy to ride and play, I recognize it also is representative of some of the challenges of bringing games — and digital accouterments — into physical spaces. Like Disneyland’s Millennium Falcon: Smugglers Run, Bowser’s Challenge takes a moment to get acclimated to. It’s a ride that gets better each time a guest rides it. That the focus is on re-riding isn’t a bad thing; I’m still noticing new things on It’s a Small World, despite having ridden it more than 100 times in my lifetime. It’s simply that the experience gets stronger as guests learn the game. I encountered plenty of attendees who had subpar initial experiences on the attraction.

Yet theme park creatives are clearly thinking about games and how to better meld them with physical spaces. Increasingly, a vast segment of theme park attendees come from a generation that was weaned on games and an interactive, on-demand lifestyle. “It’s almost impossible to have any conversation in the world of entertainment without acknowledging that gaming and digital and what [people] are doing at home is increasingly competing with what’s happening in a park or a physical setting,” said Kirin Sinha, who runs augmented reality firm Illumix, on a state of the industry panel.

“When you’re in these game worlds, you have a sense of agency,” Sinha continued. “You’re impacting the story. The world is fluid.”

Bringing such agency into a theme park has been a hot topic for a number of years. Last year, for instance, the Themed Entertainment Assn. honored Disney’s Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser with an award. Colloquially known as the “Star Wars hotel,” Florida’s Starcruiser was essentially a live-in theme park, a two-day live action role-playing game that utilized a mobile phone app to drive gameplay with real-life actors and sets. A critical success — though exorbitantly priced, I wondered if it was the future of how we would vacation — the Starcruiser shuttered after about a year of operation, failing essentially as a business enterprise.

“Let’s face it, gaming and gamers is the biggest audience we can have,” said Bruce Vaughn, the creative chief of Walt Disney Imagineering who re-joined the firm last year after departing in 2016. But how best to access that audience?

The Star Wars: Galactic Starcruiser, colloquially known as the “Star Wars hotel” and a past winner of a Themed Entertainment Assn. award, was once seen as the future of entertainment, bringing game-like techniques into a live-in theme park. The multi-day experience was shuttered after about a year.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

In the time between Imagineering stints, Vaughn helped oversee DreamScape Immersive, a virtual reality-based firm that had focused on communal games. DreamScape, too, was a critical success, but recently closed its Century City location, and announced that the company was pivoting toward educational pursuits, a further sign that succeeding outside the home with commercial XR projects — a term applied to virtual and augmented reality technologies — remains a hurdle.

Vaughn was not asked directly about any Disney projects and spoke only broadly, but stated, “None of us have really nailed it,” when it came bringing social gaming environments into a physical space.

“In my first round at Imagineering, pre-2016, we tried many things that allowed more agency and begins to touch on this,” Vaughn said, noting they failed to connect the home experience and the theme park visit in what he felt was a truly meaningful way. Vaughn theorized that things will get “more interesting as XR gets more real in the very near future. … I think that is something that we’re really craving.”

Theme parks have long been at the vanguard of technology, as evidenced by everything from lifelike robotic advancements to the all-enveloping playsets that are Wizarding World of Harry Potter and Pandora — the World of Avatar. Augmented reality, which can add a new dimension to a ride like Mario Kart or, at home, spring a board game to life, was seen as the next frontier, even if attendees were scant on specifics.

Those in the audience could speculate among themselves. Glasses that could turn Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge into a hub of spaceship activity, or flip Main Street, U.S.A. into a physical game board where Tinker Bell spreads pixie dust? Or perhaps digital overlays that dig into theme park history, allowing for guest-driven tours?

But that was just off-the-cuff guesswork. So far, a lot of augmented reality implementation in theme parks has been of the virtual “sticker” variety, that is, placing a digital character alongside a guest in a photo. It’ll get better, attendees promised.

“I’m very excited about augmented reality and what that can do. It’s going to be a bit of a disruption,” Vaughn said.

And yet that ultimately came with a warning, to build, essentially, from the bottom up and look for the tech that accentuates a product rather than the other way around. “Our product ultimately is emotion,” Vaughn said.

A fantastical nature theme permeates a China mall in Aura: The Forest at the Edge of the Sky.

(Aura: The Forest at the Edge of the Sky)

Perhaps there’s hope for the mall, after all?

Depending on who you’re talking to, the mall is either dead or on the verge of a revival. The suburban Chicago mall I grew up with is marked for closure and a reimagining, and giant department stores such as Macy’s have been struggling.

But then there’s research that points to Gen Z leading to a potential mall rebirth, arguing that malls provide both instant shopping gratification and an opportunity to be among the community. And the theme park industry has long had a rich history with malls, be it the amusement-centered Mall of America or the ways in which escape rooms and immersive art companies like Meow Wolf have found they provide the sort of big box spaces they need to create.

China’s Aura: The Forest at the Edge of the Sky attempts to split the difference between a Meow Wolf-like art exhibition and a traditional shopping experience. Developed in conjunction with New Zealand’s special effects house Wētā Workshop, Aura wants to be a mix of bold — there’s a 30-meter tall LED waterfall — and calming, as the centerpiece of the mall’s atrium is a 27-meter “Tree of Light,” which presents choreographed audio and visual shows. It’s an indoor space that serves as a love letter to nature, as designs were influenced by Eastern philosophies and strive to show that man-made structures can still be teeming with artistic life.

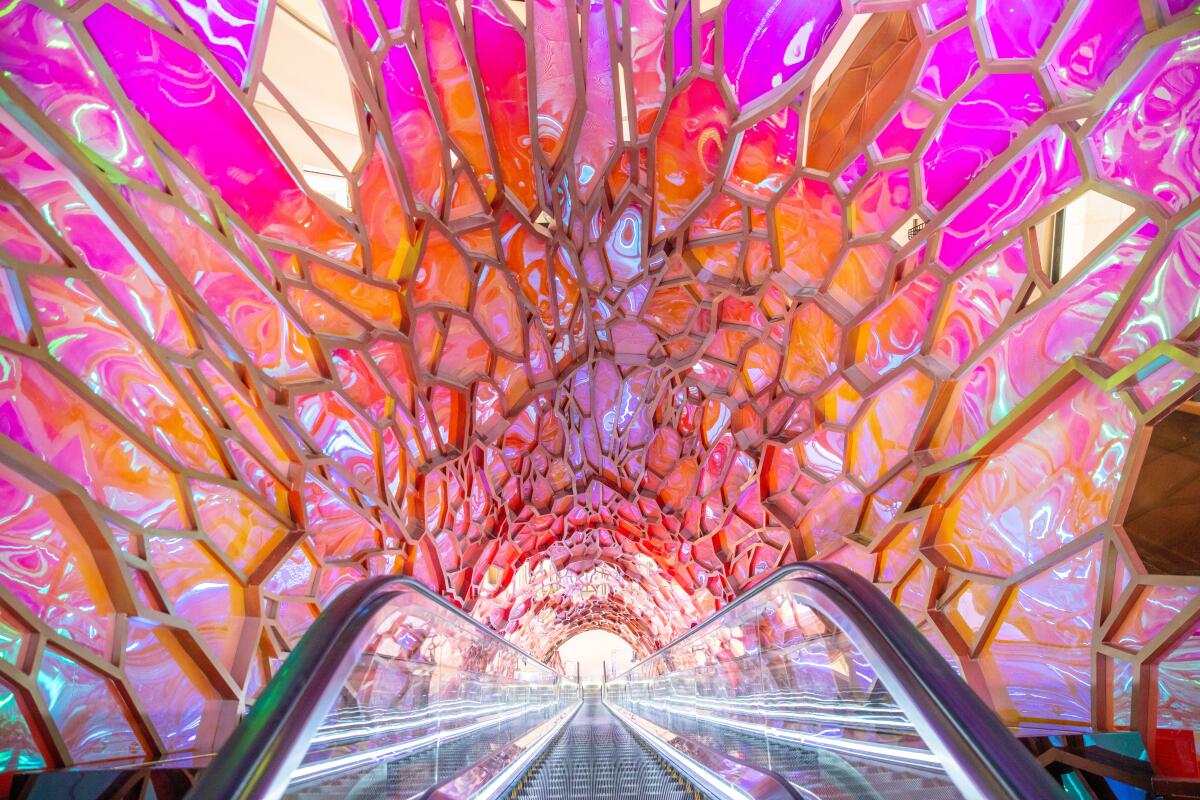

What stood out from the Aura team’s presentation was how a sense of movement permeates the space. An escalator is an excuse to create a 40-meter-long woodland-inspired tunnel, and pathways extend and weave out into the mall to circulate among the artificial trees. No one is going to mistake anything in Aura for the real thing, but that’s because it’s going for a fantastical, otherworldly look, with glowing leaves and orb-accentuated branches.

An escalator becomes an immersive art exhibit at Aura: The Forest at the Edge of the Sky.

(Aura: The Forest at the Edge of the Sky)

The overall tone is one that’s crystalline and fragile — there’s a “Tree Deer” sculpture that’s six meters high and filled with media panels, as aspects of the environment react to guest movements and actions. But rather than present a straightforward path regarding where to walk and what to touch, Wētā’s team opted to go for a sense of discovery and mystery, hiding interactive elements in nooks throughout the atrium.

“Like in nature, nothing is signposted,” said Richard Taylor, Wētā Workshop co-founder. “Surprise and discovery became an important design rule that we wanted to allow for. So for example, we didn’t want a visitor to go stand on a spot and press something and activate a thing. That doesn’t happen in nature and perhaps it shouldn’t happen in this space as well. So this thinking, that’s what we believe helped heighten the mystique of the place.”

Credit its success — in its first year of operation, Taylor said, more than 4.5 million tourists visited Aura — that form need not follow function.

“I think we are losing one characteristic of the park. That is that it is a very democratic thing,” said Andreas Andersen, CEO of Sweden’s Liseberg Group, of pay-for-access features at theme parks. Liseberg, pictured, opened in 1923 in Sweden.

(Liseberg Group)

Your time will cost you money. Expect more theme park add-ons and microtransactions.

Most Themed Entertainment Assn. events are largely focused on the creative aspects of the industry, deftly avoiding touchy business subjects to instead present the business as one big utopia centered on creating communal experiences. But there was one moment in which reality snuck in, and that’s when Al Cross of PGAV Destinations asked a theme park panel to discuss theme park pricing models, focusing specifically on up-pay initiatives such as line-skipping features.

At Universal Studios, for instance, this is known as Universal Express, which here in Hollywood can double the cost of admission to allow for one-time front-of-line access. At Disneyland, this perk is called Genie+, and typically sells for about $30 per person to allow for quicker access to an assortment of attractions. Other in-demand attractions, such as Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance, are not part of the Genie+ experience but are available as “individual Lightning Lanes,” often an additional $25 or so to purchase.

Expect such practices to continue.

“It’s one of the areas where you will see the most development in the years to come,” said Andreas Andersen, CEO of Sweden’s Liseberg Group. “I think the pay-one-price model is dying. I’m not sure if it’s a good or bad thing. It will also impact design.”

How, exactly, it will influence design wasn’t unraveled, but many in the industry are eagerly looking forward to Universal Studios’ Epic Universe, under construction in Orlando and soon to be home to four core mini-parks — immersive lands, essentially — themed to Nintendo, “How to Train Your Dragon,” the “Harry Potter” universe and the company’s legacy with monster films.

Though Universal has not yet detailed a pricing structure, it’s widely anticipated within the industry that the company will offer some sort of pay-as-you-go or a la carte model, in which guests can mix and match which of the lands they will visit on a given day. No doubt there will be a premium ticket that provides access to all four “portals,” as Universal is calling them.

“It kind of also maybe reflects the time we’re in, that we want something much more individualized,” said Andersen.

Imagineering’s Vaughn — quickly joking that such a topic was one his public relations team warned to be “cautious” on — said it’s also an area in which theme parks will rely on artificial intelligence, especially when it comes to helping guests plan a day or a vacation. “The genie is out of the bottle,” Vaughn said.

Walt Disney Imagineering creative chief Bruce Vaughn envisions a future when theme parks will utilize technology to better plan a guest’s day. The Walt Disney Co.’s Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind, at Florida’s Epcot, is pictured here and was honored with a Themed Entertainment Assn. award.

(Kent Phillips / Disney)

Currently, Disney’s Genie does attempt to help a guest program their day at a Disney theme park, but it’s in its early days and relatively rudimentary. Rare, for instance, is a day when Genie recommends something I actually want to do or a place I want to eat, but I can foresee some simple modifications to improve the guest experience. Say someone wants to dine at a particular restaurant. Rather than regularly checking the app to see if wait lists are open, the app should be able to alert a guest when the wait list is in fact open and if they would like to be added to it.

“We’re in this rough phase where we’re all charging more money to pay for a more expensive product,” Vaughn said. “But at the end of the day, we know how much people are willing to pay … if they get what they want.”

What Vaughn foresees is “a world of truly predictable itineraries and customizable itineraries” that can “begin to have a dialogue with the guest to understand” what more they would like to do at the theme park. All panelists essentially agreed that today’s culture values time as much as money.

Liseberg’s Andersen, however, was a voice of reason, reminding attendees and panelists that theme parks were once envisioned as shared experiences for all walks of life.

“I hate these programs,” Andersen said. “I understand that they work and they are financially very profitable, but I think we are losing one characteristic of the park. That is that it is a very democratic thing. It’s a place you can go and are like everyone else. I think we are losing something when we take this route, but I also understand we kind of have to. But I don’t like it.”

Theme parks can be magical spaces, places that reflect a culture’s myths and stories back to us, and allow us to connect with friends, loved ones or even strangers. But they can also be high stress, where one, after shelling out hundreds to get in the gate, will learn that a level playing field is impossible as they’re prodded to pay more for additional features.

A look at the 300-seat moving platform themed to a ship that is the ride vehicle for Bermuda Storm.

(Chimelong Group)

Rides can get bigger — and explore powerful themes

To end on a more uplifting note, let’s go back to China, specifically to the indoor aquatic park Chimelong Spaceship in Zhuhai.

Here lies Bermuda Storm, a giant 300-seat simulator platform designed to mimic a large seafaring vessel and sit in a sort of all-encompassing multiplex. Credit international destinations with keeping theme parks weird, and the Bermuda Storm doesn’t disappoint. Here in the states, new attractions — last year’s Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind at Walt Disney World’s Epcot or the upcoming “Fast and the Furious” coaster at Universal Studios Hollywood — are most always wedded to known intellectual property. But not everyone has access to a film franchise, and the themed entertainment world is richer for it.

What Bermuda Storm does have are animatronic figures, in this case a ship-guiding ape — he’s the “First Primate” — and a topsy-turvy motion platform designed to mimic a trip-gone-wrong to the Bermuda Triangle. The attraction’s original name was the delightfully to-the-point Disaster Theater, but the current Bermuda Triangle designation gives less away. The ride, after all, starts with reggae music and chill vibes. Feel wind, feel maybe some splashes of water, but all is calm, until, well, the storm. And then there are pirates. And then there’s a kraken.

But this kraken is no mythical sea monster. “We conjured a massive and grotesque sea creature grown from all the pollution and the debris that humans have been pouring into oceans and rivers for centuries,” said Rick Rothschild, who heads Far Out! Creative. “Seems like a perfect villain for our story’s finale, while also speaking to the Spaceship’s message of safeguarding the water and protecting the ocean.”

Tapping into conservation elements isn’t exactly a theme park rarity — Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida makes it a priority — but it’s welcome to see such a message in a fantastical, borderline thrill ride for 300 people. And it’s tantalizing to see the topic of sea pollution treated so otherworldly.

Most important, it’s an argument that theme parks remain as unique — and fantastical — as the cities and countries that house them.