On Saturday, the Election Commission of India – the country’s independent poll-conducting body – announced the dates for a democratic exercise that is unmatched in scale globally, and in history.

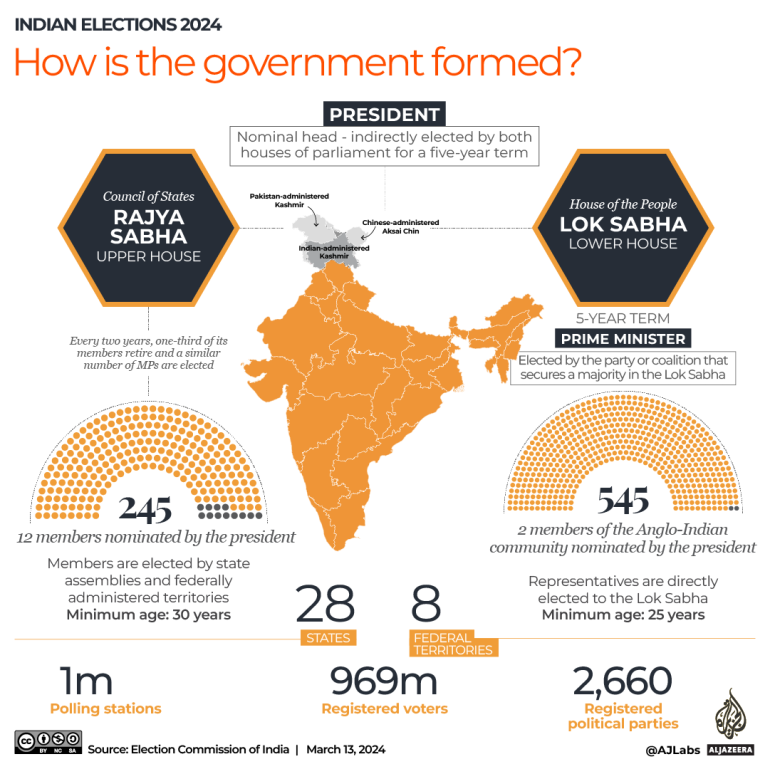

From the Himalayas in the north to the Indian Ocean in the south, from the hills of the east to the deserts in the west, and in concrete jungles that are some of the world’s biggest cities to the smallest of villages, an estimated 969 million voters are eligible to cast their ballots. They will elect 543 politicians to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament. Two other members are nominated, to make up a total strength of 545 in the house.

India’s election is colossal, colourful and complex. Here are seven ways in which it is unparalleled in size.

82 days, seven phases

The election process that started on Saturday will continue for 82 days until results are announced on June 4. With the announcement of the schedule, a model code of conduct also kicks in – campaign rules now apply, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government is not supposed to announce new policies that could influence voters.

Voting will run in seven phases from April 19 to June 1, said Rajiv Kumar, chief election commissioner of India. The counting of votes will take place on June 4. Assembly elections for the states of Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha and Sikkim will also take place along with the national elections.

After April 19, the other voting dates are April 26, May 7, May 13, May 20, May 25 and June 1. Some states will complete voting on a single day, while others will have voting spread out across several phases.

Over the years, the number of days over which voting has stretched has varied a lot – from the shortest ever four days in 1980 to 39 days in the 2019 election, to 44 days in 2024.

The primary reason for the multiphased election is for the deployment of huge federal security forces required to check everything from polling-related violence or attempts at rigging, according to N Gopalaswami, the former chief election commissioner of India.

Still, staggered polls are no guarantee for free and fair elections as longer campaigning favours the ruling party of the day, said N Bhaskara Rao, chairman of the New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies, and a pioneer in election research in India. Rao argued that the process should be shortened. The longer the process, the more the opportunity for the ruling party to use government infrastructure to campaign.

969 million voters

The size of India’s electorate is more than the population of all the countries of Europe combined.

They will cast their votes through 5.5 million electronic voting machines at 1.05 million polling stations, of which some are located in the snow-clad mountains in the Himalayas, the deserts of Rajasthan and sparsely populated islands in the Indian Ocean.

The Election Commission will deploy about 15 million polling staff and security personnel to conduct the elections. They will trek across glaciers and deserts, ride elephants and camels, and travel by boats and helicopters to ensure every voter can cast their ballot.

A $14.4bn election bill

It is expected to be the world’s most expensive election. Spending by political parties and candidates to woo voters will likely cost more than 1.2 trillion rupees ($14.4bn), said Rao, whose organisation regularly estimates the country’s poll expenditure.

That would be twice what was spent in India’s 2019 elections – 600 billion rupees ($7.2bn). The total spending on the US presidential and congressional races in 2020 was also $14.4bn.

Most of India’s election spending is not publicly disclosed. Candidates spend unaccounted money to woo voters. The election scrutiny machinery is weak in detecting cash transactions, said Gopalaswami, referring to attempts by candidates to directly bribe voters with money or other enticements, from alcohol to clothes.

Polling booth at 15,256 feet

Holding elections in the world’s seventh largest nation by area is a complex task.

In 2019, election workers travelled 300 miles (482 km) over four days across winding mountain roads and river valleys to set up a polling booth for one voter in the northeastern state of Arunachal Pradesh, which borders China. Beijing claims a part of the state, and ensuring elections are held there is vital for New Delhi to demonstrate its sovereignty over the region.

Election officials also set up a voting booth at 15,256 feet (4,650 metres) in a village in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh, making it the highest polling station in the world. Far off the country’s east coast, on the remote Andaman and Nicobar Islands, workers travelled through crocodile-infested mangrove swamps and dense jungles to reach polling booths.

In Malkangiri district of Odisha, where left-wing Maoist fighters have a presence, polling staff walked 15km (9 miles) through forests and hills to protect electronic voting machines from the rebels after voting. Intelligence agencies had warned them that using cars could have made them easier targets.

“On sheer numbers, it’s gigantic and complicated, but in a sense simple also because at each level the law is very clear about what are the duties and responsibilities of each polling official,’’ said Gopalaswmi. “Complications are arising as competition is becoming fierce,’’ he said, adding, that implementation of the model code of conduct has become increasingly challenging for the election commission.

2,660 parties

A multiparty democracy, India has about 2,660 registered political parties. Parties competing in elections each get symbols – like the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s lotus, the opposition Congress party’s hand, and others, ranging from an elephant to a bicycle, and a comb to an arrow. These to help voters easily identify candidates, in a country where almost a quarter of the population is not literate.

In 2019, seven national parties, 43 state parties and 623 unrecognised political parties participated in the elections. Parties that have a significant footprint in a state legislature are recognised as state parties. Those with a meaningful presence in multiple states get the national party tag.

In 2019, 36 parties were able to win one or more seats in the Lok Sabha. In all, about 8,054 candidates, including 3,461 independents, contested those elections. Of the 543 winning candidates, 397 were from national parties, 136 were from state parties, six were from unrecognised parties and four were independent.

A record 612 million people of a 912 million strong electorate cast their votes in the last election, registering the highest ever voter turnout at 67.4 percent. Women’s participation also increased to an historic 67.18 percent in 2019.

303 against 52

The principal protagonists of the 2024 battle are Prime Minister Modi and his BJP, who lead a coalition of more than three dozen parties; and the main opposition Congress party-led alliance of about two dozen parties.

In 2019, the BJP secured a landslide victory with 303 seats. Its coalition had a total of 353 seats. The Congress party won got 52 seats, and 91 with partners.

Currently, the BJP is in pole position following recent state victories and is expected to win a majority, according to opinion polls. The BJP alone controls 12 of India’s 28 states, while the Congress governs in three states.

Still, Indian political history is littered with instances of parties winning major state elections only to lose the national vote soon after. The BJP knows that better than most: In 2004, its then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee called early elections after winning the key state elections of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh before losing the Lok Sabha vote to a Congress-led coalition.

370 or 404?

Modi has set a target of 370 seats for the BJP, 67 more than in 2019; and for its alliance to cross 400 seats. He is seeking a third term in office.

The last time any party crossed 370 seats was in the 1984 election. The Congress party won 414 seats following the assassination of the former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

If Modi wins and completes five years, he will be the third longest serving prime minister in Indian history. The country’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru ruled for about 16 years and 9 months consecutively, while his daughter Indira Gandhi governed for a total of about 15 years and 11 months.