A nine-member high-level panel headed by former President Ram Nath Kovind on Thursday recommended amendments to the constitution to hold national and regional polls together.

The move, supporters, say will save time and money while allowing political parties and governments to focus on policy and administration. However, critics say it would go against the federal structure and spirit of the Indian constitution, cloud local issues that get attention when state elections are held separately, and potentially turn all votes subsumed in the giant election exercise into a prime ministerial contest.

The panel’s recommendation won’t have any bearing on the national elections which will kick off in a few days — but the coming vote could set the stage for the plan’s execution five years from now.

Here’s what the controversy is about:

What is ‘one nation, one election’?

Simultaneous elections are broadly aimed at ending frequent election cycles — about 30 polls were held for elections to states and union territories from 2019 to 2023, besides the 2019 general elections.

A single election would mean that voters would cast their ballot for electing members for all tiers of the government in one go, or at most on two days.

Elections were held concurrently for nearly two decades after 1951. The practice was disrupted in 1967 with the premature dissolution of some state legislative assemblies. The practice of conducting simultaneous elections exists in some countries including Sweden, Belgium, Germany and the Philippines.

The idea to bring the practice back to India is not new. The Law Commission, which provides advice to the government, had recommended simultaneous polls in 1999 — a quarter of a century ago.

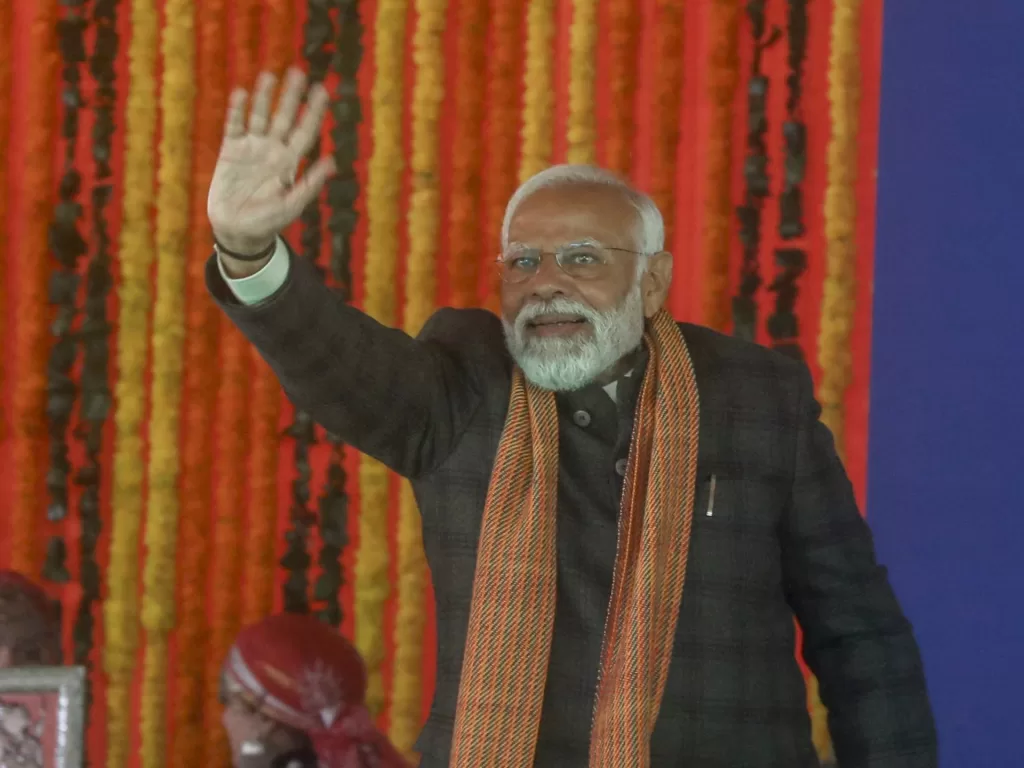

Since he came to power in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been pitching the idea in public forums.

What are the key recommendations?

The panel in its 18,626-page report has outlined a phased approach to synchronise elections — beginning first with elections for the lower house of parliament or Lok Sabha and state assemblies, followed by elections to local bodies within 100 days of general polls.

The president of India will notify a date for the first sitting of the Lok Sabha after a general election. This date will mark the new electoral cycle.

Former President of India Shri Ram Nath Kovind who heads High-Level Committee (HLC) on ‘One Nation, One Election’ presented the report on simultaneous elections in the country to President Droupadi Murmu along with members of the HLC including Union Home Minister Shri Amit Shah,… pic.twitter.com/wqlPZ3n0FV

— President of India (@rashtrapatibhvn) March 14, 2024

The tenure of all state assemblies formed after that date will be curtailed to coincide with the subsequent general elections.

In the event of a hung house and a no-confidence motion, new elections will be held to constitute the new lower house of parliament or state assembly — but only for the remainder of the five-year term.

What would be needed to hold joint polls?

The move to hold simultaneous elections for the Lok Sabha and assemblies can be done by amending the constitution, without having to get it endorsed by state legislatures.

But for synchronising votes for local bodies with general elections, amendments to the constitution will need the ratification of at least half of India’s 28 states.

The elections will also involve common electoral rolls and a single voter identity card for all polls.

Conducting simultaneous elections is possible, but the Election Commission of India will need three times as many electronic voting machines as it currently has, said SY Quraishi, former chief election commissioner.

It will also need many more than the 15 million polling staff and security personnel currently used for national elections, he said.

What are the arguments for and against this move?

Of the 47 political parties that gave their opinions to the panel, 32 supported the idea, while 15 opposed it.

The main opposition Congress party told the panel that implementing simultaneous elections would result in “substantial changes to the basic structure of the constitution”, go against “the guarantees of federalism” and “subvert parliamentary democracy”.

The All India Trinamool Congress, which rules in the eastern state of West Bengal, said forcing state assemblies to hold premature elections just for the sake of simultaneous votes would be unconstitutional and would ultimately lead to suppression of state issues.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has supported the concept by arguing that about 800 days of governance are effectively lost over five years. Ahead of every election, the election commission announces what is known as the Model Code of Conduct: After that declaration, until the elections are over, relevant governments can’t enforce any new policies that might affect voter choices.

Simultaneous elections will spur growth, cool inflation and avoid disruption of supply chains, while also optimising resources spent on polling and encouraging large-scale voter participation, the panel has said.

But Quraishi, India’s former election commissioner, argued that if many state assemblies are dissolved early just for them to hold new elections at the same time as the national vote, that would actually increase the total number of elections. And not just in the short run: If governments fall, and new elections are held for held for truncated tenures, that too would increase the total number of elections.

“It’s not a very brilliant idea,” Quraishi said.

Trilochan Sastry, founding member of the Association of Democratic Reforms, a group that advocates for greater political transparency and accountability, echoed Quraishi’s worries. And if India wants to cut the rising cost of elections, it can do so by capping campaign spending by parties, Sastry said.

Simultaneous polls could also give an advantage to the party ruling at the national level, said Quraishi.

According to a study by the IDFC Institute, a think tank, there is a 77 percent chance an Indian voter would support the same party at the federal and state level if elections are held simultaneously.

Political accountability activists also argue that frequent elections might actually be good — they put pressure on governments and parties to stay on their toes and remain sensitive to voter concerns.

“We are living with the current system of frequent elections,” said Sastry. “Now if you suddenly change the system, we have to examine all implications and hold wider consultations.”

What is the price for holding polls together?

Elections in India are costly affairs – the world’s most expensive.

Election expenditure by political parties and candidates for simultaneous polls could be 10 trillion rupees ($121bn) for five years starting in 2024, said N Bhaskara Rao, chairman of the New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies. Of these, 1.2 trillion rupees ($14.5bn) will be spent for this year’s general elections. Most of this spending is unaccounted for.

About 3 to 5 trillion rupees could be saved if simultaneous elections idea is adopted, said Rao.

The panel said simultaneous elections could help a 1.5 percentage point increase in GDP, which is equivalent to 4.5 trillion rupees ($54bn) in the financial year 2024, half of the public spending on health, and one-third of that on education.

Still, some argue that costs alone can’t be a determining factor for holding all polls together. The Congress party told the panel that the “argument that cost of conducting elections are extremely high seems baseless” and described it as “the cost of free and fair elections to uphold democracy”.

Can it become a reality?

Very possibly, if Modi’s BJP-led coalition comes to power with a clear majority after the April and May parliamentary elections. Ratification by states won’t be difficult as the BJP alone controls 12 of India’s 28 states and has allies ruling several others.

The BJP is in pole position for the 2024 general elections. Opinion polls suggest the BJP-led alliance will win with a clear majority.

Simultaneous polls have been an electoral promise of the BJP. And if the party returns to power this year, this transformation of Indian electoral democracy could become a reality in 2029.