But proposals by Tokyo to cancel the permanent residence (PR) status for those who fail to pay their taxes and social insurance contributions are now calling that security into question, stirring unease among some longtime foreign residents.

Ben Shearon, a British native who has lived in Japan for almost 24 years, is among those questioning the rationale behind the proposed changes to immigration law.

A permanent resident, Shearon retired in 2022 and now spends most of his time working on his website RetireJapan, where he offers coaching and financial advice to Japan’s expatriate population.

“I am not worried about my own status in Japan. I have paid all my taxes, and I have also been paying into the national health insurance and public pension in Japan since I arrived,” Shearon told Al Jazeera.

“My main issue at the moment is that the headlines seem to feed a narrative that foreign residents, especially permanent residents, are not paying their fair share.”

Under the standard process for obtaining permanent residency, applicants must have lived in Japan for at least 10 years and held a work visa for five of those years.

But since 2017, foreign residents have been able to fast-track the process to as little as one year if they score highly on a points-based assessment that looks at work experience, salary, academic qualifications, age and Japanese language proficiency.

The law also states that a foreigner’s permanent residence must be in the best interests of Japan, which includes paying taxes, pension contributions and health insurance premiums.

At present, the government can only revoke an individual’s permanent residence in a narrow set of circumstances, including being sentenced to more than one year in prison.

Under the proposals, authorities would be able to cancel residents’ visas over the non-payment of taxes and prison sentences of less than one year.

‘Small minority’

Shearon, like other foreign-born residents, is concerned that the proposals single out non-Japanese citizens for special scrutiny.

“I’m also not a fan of creating new penalties that only apply to foreigners when we already have laws and consequences for not paying tax that apply to everyone in Japan equally,” he said.

“If not paying health insurance or pension is a significant problem in Japan, then surely the way to address it is to strengthen enforcement for everyone, not just focus on a small number of a small minority.”

Permanent resident visa holders currently number about 880,000 in Japan, less than 1 percent of the population.

Since the announcement of the proposals last month, foreign residents reacting to the plans have generally fallen into one of two camps.

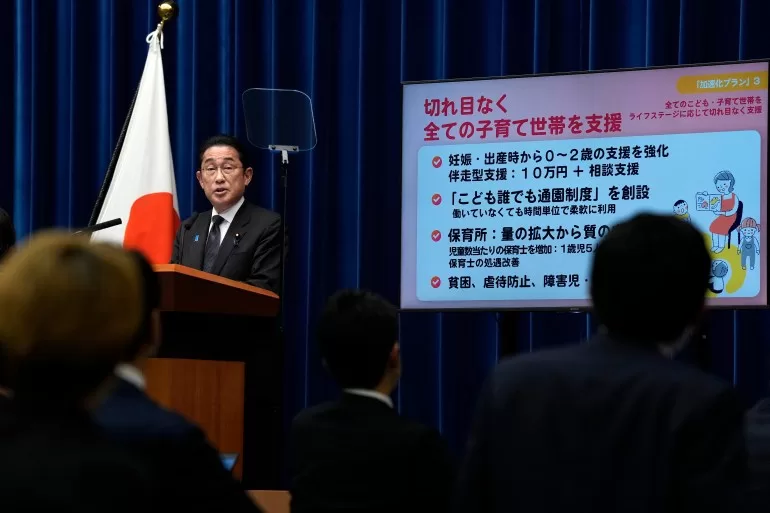

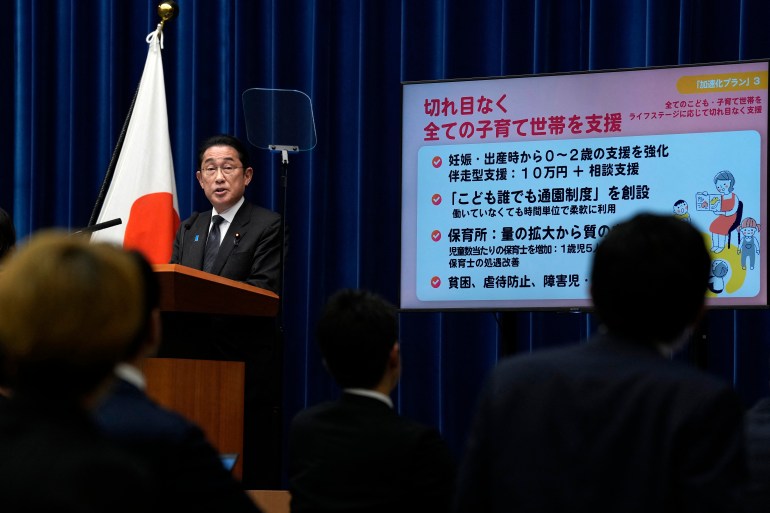

While some see Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s administration stoking xenophobia, others have scoffed at the suggestion foreigners are being singled out, arguing that tax evaders should be punished and only those seeking to game the system have anything to fear.

“What are these gaijin even complaining about? If you already pay your taxes, congratulations. You have nothing to worry about,” Oliver Jia, a Kyoto-based researcher and writer, said on X in response to a post decrying the proposals as discriminatory.

“Do these people realize that permanent residence by default means you have less rights than citizens? That’s how virtually every country on earth functions,” Jia added.

“Japan isn’t going to bend over backwards for you, especially because you’ve decided you don’t want to pay taxes. Unhinged.”

Austin Smith, public policy manager at GR Japan, a politically neutral government relations and advisory firm, said the proposed amendment would water down permanent residence status, but only to an extent.

“PR visa revocation will likely still be a rarity, but it will be more common than under the current system,” Smith told Al Jazeera.

“Still, even a slight increase in the likelihood of having one’s PR status revoked is bound to worry foreign residents, many of whom have built their lives around Japan.”

Smith said he believed the measures would most likely only be applied to those who knowingly committed tax evasion or crimes resulting in imprisonment.

“There are concerns, however, that this could affect those unable to pay taxes due to job loss or other factors,” Smith said. “Or that it could be expanded in the future to enable revocations for crimes resulting in fines.”

The move comes despite a push by Japan to attract more immigrants as it faces rapid population decline.

In recent years, municipalities throughout Japan have simplified the pathway for obtaining visas for startup owners and business managers.

Later this month, Tokyo is set to launch a new digital nomad visa, targeting remote workers from 49 countries who earn more than 10 million yen (about $67,000) a year.

Japan’s foreign trainee programme, which has often been maligned as a cover for importing cheap labour since its introduction in 1993, is undergoing a sweeping overhaul to make it easier to transition to being a skilled work visa holder, and, eventually, permanent resident.

In late February, the government also eased visa regulations to allow more foreign students to find jobs in Japan after they’ve completed their studies.

According to official forecasts, Japan’s population is on track to shrink from about 125 million to fewer than 80 million by 2070.

Policymakers see higher levels of immigration as one way to replenish the workforce and avoid a further slowdown in the country’s already meagre economic growth rate.

Smith said he is sympathetic to the need for more immigrants but does not see the proposed changes to the permanent residency rules as necessarily in conflict with Japan’s turn towards pro-immigration policies.

“The goal here for lawmakers seems to be aligning PR visa revocation conditions with the guidelines for securing PR status,” he said.

“[But], I think Japan needs to make immigration more accessible to curb some of the negative impacts brought about by an ageing society … Japan will need to ensure its labour market is attractive to a wide range of potential workers from overseas and that its immigration system is flexible and welcoming.”