It was a steamy August afternoon in Bulumkutu, Maiduguri, Nigeria. The kind that makes people sullen with discomfort.

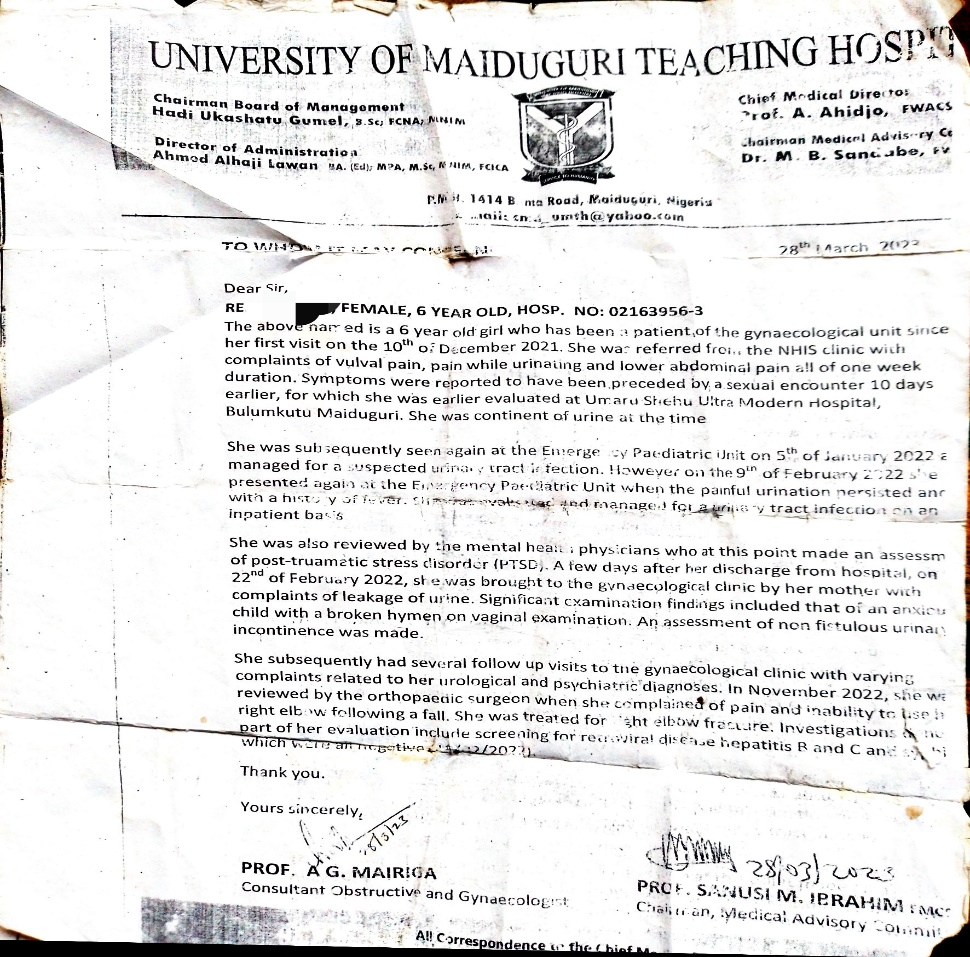

I found Hassana Ibrahim* smiling at her now 6-year-old daughter, Maimuna,* sitting on a mat. Mrs Ibrahim raised her head with the same smile as she welcomed and offered me a seat beside her. As I explained why I was there, her face filled up with anger as she narrated her daughter’s story: Maimuna was sexually abused at the age of five.

“I reported to the police immediately, before even taking her to the hospital, with all the evidence gathered. The police said it was confirmed that Modu*, who molested my daughter, was 16 years old, so he cannot be convicted,” Mrs Ibrahim remembers.

Modu lives in the same neighbourhood, and Mrs Ibrahim* lamented how she watched him get away with sexually abusing her daughter because he claimed to be 16. “I cried over what happened to my daughter almost every day, knowing that I am helpless to get her justice,” she said.

According to Mrs Ibrahim, Modu continued to stalk and harass Maimuna because his family supported and protected him. Mrs Ibrahim told me how they attempted to collectively beat her up when the incident occurred. “Whenever Modu sees Maimuna, he calls her “Kamunyi” which means my wife in the Kanuri language. I reported to the state National Human Rights Commission and the police again, but no action was taken.”

Tragically, Modu raped Maimuna a second time when she was six and Mrs Ibrahim furiously lamented how the community and the system are still failing Maimuna and other children by enabling Modu.

“I was sweeping in the house when some boys ran in, carrying her in their arms. She was unconscious and bleeding. I felt like dying at that moment as I listened to them telling me how they found her lying under a tree. I quickly rushed her to the hospital. The doctors examined her, and I still have the three underwear that I changed for her because I do not want to make the mistake of losing any evidence,” she explained.

Cases delayed

The police are relaxed and slow in their investigations, and Mrs Ibrahim no longer has faith in the system that should protect her and her daughter, she says.

“At the police station, I was assured that I will get justice for my daughter but I have started losing faith in the police and what they are doing with the case. They still did not forward the case to the court, though Modu is still in the custody of the police,” she said.

Modu’s family took legal steps against Mrs. Ibrahim, accusing her of slander. “I was summoned for a court hearing on 10th August 2023, I thought it was about my daughter’s case, but the story was different as they said I lied against their son. The court sitting was adjourned to 5th September 2023, and I am confused as to why the court will even consider their allegation that I lied against their son. I can feel my daughter’s pain and I am afraid of what she must face in the future because of this. I desperately need justice for Maimuna.”

Mrs. Ibrahim* noted how a friend suggested that she contact FIDA, and how FIDA’s swift action helped her. “Three days to 5th September, FIDA sought intervention from the Borno State Ministry of Justice and the ministry notified the Chief Judge that there is a criminal case against the boy, so when we arrived at the court on the fourth day, the Chief Judge dissolved the case,” She narrated.

The International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) is a Non-Governmental, Non-Profit Organization made up of women lawyers. FIDA is the acronym for the Spanish name “Federación Internacional dé Abogadas.”

“I was a victim, too”

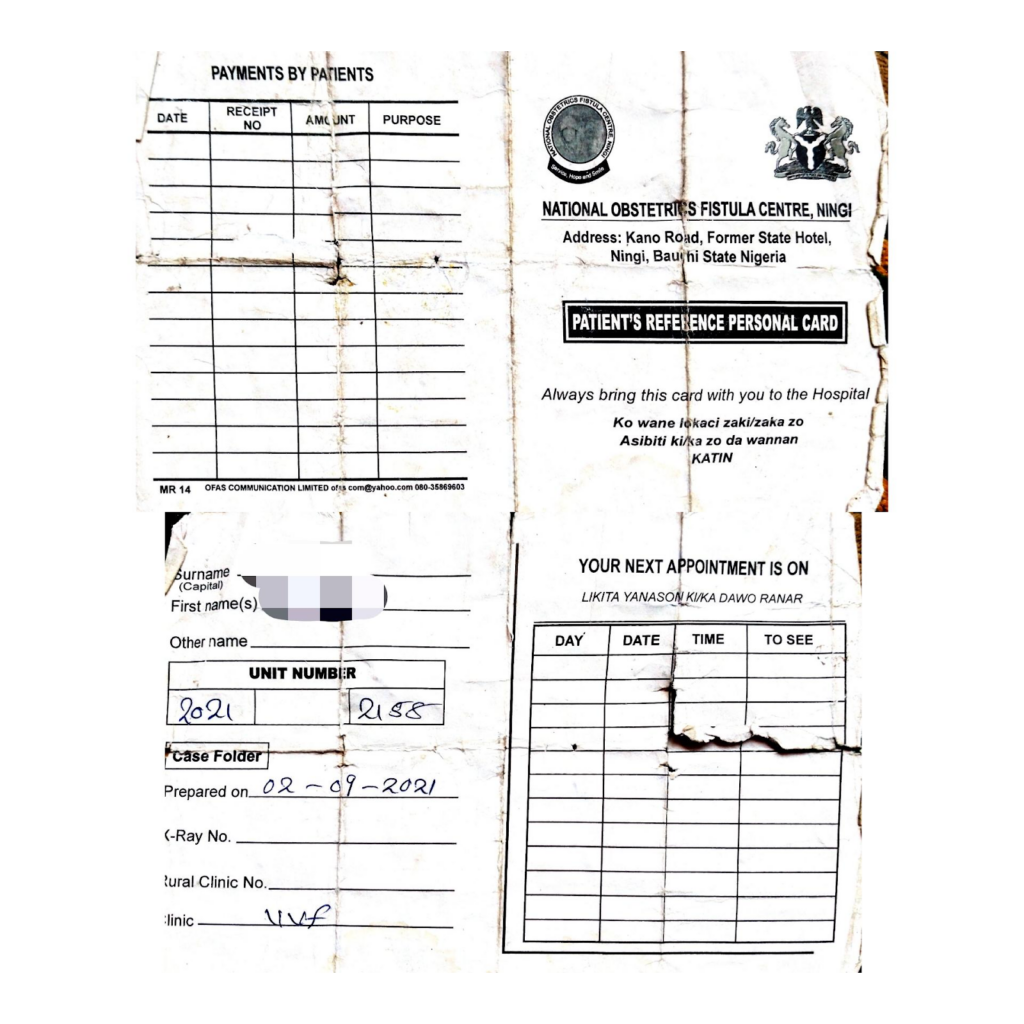

Mrs Ibrahim was sexually assaulted at the age of three, at Baga local government area in Borno State where she was born. She got married at age 17 and at age 30 she is still suffering Vesicovaginal fistula (VVF).

Early marriage often results in physical or psychological consequences that can lead to numerous diseases such as VVF. Vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) is an abnormal fistulous tract extending between the bladder and the vagina that allows the continuous involuntary discharge of urine into the vaginal vault. VVF is often caused by childbirth in which case it is known as an obstetric fistula, when a prolonged labour presses the unborn child tightly against the pelvis, cutting off blood flow to the vesicovaginal wall. The affected tissue may die leaving a hole. Vaginal fistulas can also result from particularly violent cases of rape, especially those involving multiple rapists and/or foreign objects.

“I dropped out of school and was divorced two weeks after my first marriag because of VVF.” Mrs Ibrahim ran helter-skelter in search of a remedy. She travels frequently from Bauchi state to Maiduguri for routine checks at the hospital spending the little money she has on medical care and transportation with no solution to her predicament. “This is my deepest secret but if it will help me find justice for my daughter’s ordeal, then I will expose it for the world to see, maybe someone will come to my aid,” she lamented.

Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) highlighted ‘Best interest of the child’, said “Governments should make sure children are protected and looked after by their parents, or by other people when this is needed. Governments should make sure that people and places responsible for looking after children are doing a respectable job ” Also, Article 3 of the UNCRC, states that “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” This means that all children and young people should be prioritised in all levels of society and that their rights should be respected by people in power. Article 3 is related to other articles that affirms the right of the child to life, survival, development and participation. According to section 38 of the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act “Every victim is entitled to receive the necessary materials, comprehensive medical, psychological, social and legal assistance through governmental agencies and/or non-governmental agencies providing such assistance” and “Victims are entitled to be informed of the availability of legal, health and social services”.

In 2021, the Guardian Newspaper reported that the Borno State Government recorded 4,104 cases of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) in 7 months with the Ministry of Women Affairs disclosing that 3,805 of the victims were females. In 2022, the National Human Right Commission (NHRC) recorded 495 Sexual and Gender Based Violence (SGBV) cases in Borno state.

Communities lack awareness

Sixteen-year-old Zainab Isa* shared her bitter story of how her life was in turmoil following abuse at an early age.

“I was raped at 15 by a man called Bana in 2022 when I was growing up at Bula-Bulin Garanam in Borno. I became pregnant, Bana ran away from the community and my parents rejected me.”

Zainab has no financial support and she is unable to take care of herself and the pregnancy. She became traumatised when her parents sent her out of the house when they found out she was pregnant. Zainab lost interest in associating with her age-mates.

“My grandmother, Iyya, was the one who accommodated me. Iyya is incredibly old and could not even take me to the clinic. We could not gather evidence nor seek any authoritative intervention through available Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) at the time. Three months after, a woman came to our house and told my grandmother that there was an organisation called Save the Children that could help me seek justice. Iyya did not hesitate to take me there, and she pleaded with them to help us find justice, but they said it is impossible because we did not have any evidence to prove I was raped. They enrolled me in weekly counselling sessions and orientation on how I can take care of my pregnancy.”

Although Iyya is ready to fight for her granddaughter’s rights, she is more concerned about lack of money and confidentiality if she is to take her granddaughter to the police station.

Grace Yakubu, a GBV case worker with Save the Children at Bulabulin Garanam, Maiduguri Metropolitan Council (MMC), explained that throughout their activities for over a year in that community, they did not come across any government appointed social worker.

“The people living in this community are partly ignorant of many things regarding SGBV including how they can secure evidence and the process of reporting. They have continually expressed their concern about community leaders not wanting them to report SGBV cases to authorities, so I believe community sensitisation would have helped, but there are no social workers here,” Grace Yakubu said.

Inactive social workers

The lack of social workers in Borno is not limited to the ones in MMC. Other resettled communities also do not have any active social workers supporting victims of SGBV. A social welfare field worker in Bama LGA, who only agreed to speak on anonymity, disclosed that he has not been to work for over seven years because of a lack of engagement and poor functioning of the social welfare Unit. “After the resettlement, I didn’t go out to work, I am not engaged in doing anything except for emirate meetings sometimes, but my salary is flowing,” he affirmed.

Similarly, Ya Hajja, a serving social worker at Jere LGA, confirms that she has not been to work for about nine years, while trying to justify her actions with a lack of support from the government. “I stopped going to work around 2013-2014, but I am not to blame for it. The last time our hazard allowance was paid was around 2011. We also need welfare and other support. Do you expect us to use our salaries to manage sensitisation or go up and down on people’s cases?” She questioned.

I spoke to the Executive Director of Women in the New Nigeria and Youth Empowerment Initiative (WINN), Comrade Lucy Dlama Yunana, who stated that the lack of social workers makes their work complex.

“This has been a great setback to our various interventions in Borno because the social workers are supposed to be there permanently for these communities. We are supposed to be handing over cases to them as government agents,” Comrade Lucy explained.

I also spoke to the Social Welfare Director at the Ministry of Women Affairs and Social Development, Borno state, Mrs. Aishatu Shettima and identified the lack of social workers as a challenge faced by her department.

“Most of our workers have aged, many have retired, and we haven’t had any recruitment for a very long time. One social worker is managing three locations, and we do not even have available social workers,” she said. Mrs. Shettima informed me that to work as a social worker means to sacrifice one’s time, energy and resources to ensure public welfare is delivered. She appealed to the government to enable them by recruiting social workers for them to be able to give efficient welfare services to the community. “We are calling on the state government to consider recruitment in this department and ensure their welfare as workers, though we have been supporting some that are active with transport fare from our end,” she explained.

The law needs evidence

There is a need for the public to be informed and educated on taking legal action in cases of abuse, violence and any form of harassment. The Secretary, International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) Borno state branch, Barrister Fatsuma Salihu, said, “It is of great importance for the public to know where to report, when to report, and to whom SGBV cases should be reported. Many of our people follow the wrong channel, and before the redirection takes place, they lose some vital information that will be needed in the court because the law works in due process and needs comprehensive evidence to convict offenders.”

Hassana Ibrahim told me that despite having all the evidence of abuse, her case has not been heard in court yet. “I have all the required evidence; what else do they want from me? This is the second time it has happened, so I made sure I didn’t lose any of the evidence,, including the medical report. I am tired of the process because, with all that has been happening, my case hasn’t reached the court yet. We need help,” Maimuna’s mother appealed.

Social welfare workers I spoke to agree that the Borno state government needs to consider the recruitment of active social workers in order to achieve an SGBV-informed society. Government agencies, Non-Governmental Organisations, and the Court also need to ensure transparency while managing cases for survivors to be aware of the processes and available justice, so that people like Mrs. Ibrahim and her daughter get the justice they deserve in the end.

All names with asterisks were changed to protect sources.

This story was done with support from Women Radio Centre and the MacArthur Foundation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.