Conlon’s departure from his leadership role coincides with that of Los Angeles Philharmonic’s music director, Gustavo Dudamel, who last year announced his plans to leave the L.A. Phil for the New York Philharmonic in 2026. In an interview with The Times, Conlon called the timing “a total coincidence,” but the simultaneous loss of two of the city’s most notable artistic leaders will nonetheless signal a sea change for the classical music scene in Los Angeles at a time when the city is awash in rich cultural and musical offerings and has distinguished itself as a center of cutting-edge artistic experimentation and expression.

Who Conlon and Dudamel’s successors will be is now almost as important as the tremendous legacies both are set to leave behind.

“I will look forward, together with [President and CEO] Christopher Koelsch, to find a good succession and we worked a long time on this to be sure that the public and the organization have a sense of continuity,” Conlon says. “I’m in good health. I have a lot of energy left, a lot of passion left. And there are other things that I feel I have wanted to do and I just can’t. I can’t do them without dedicated time.”

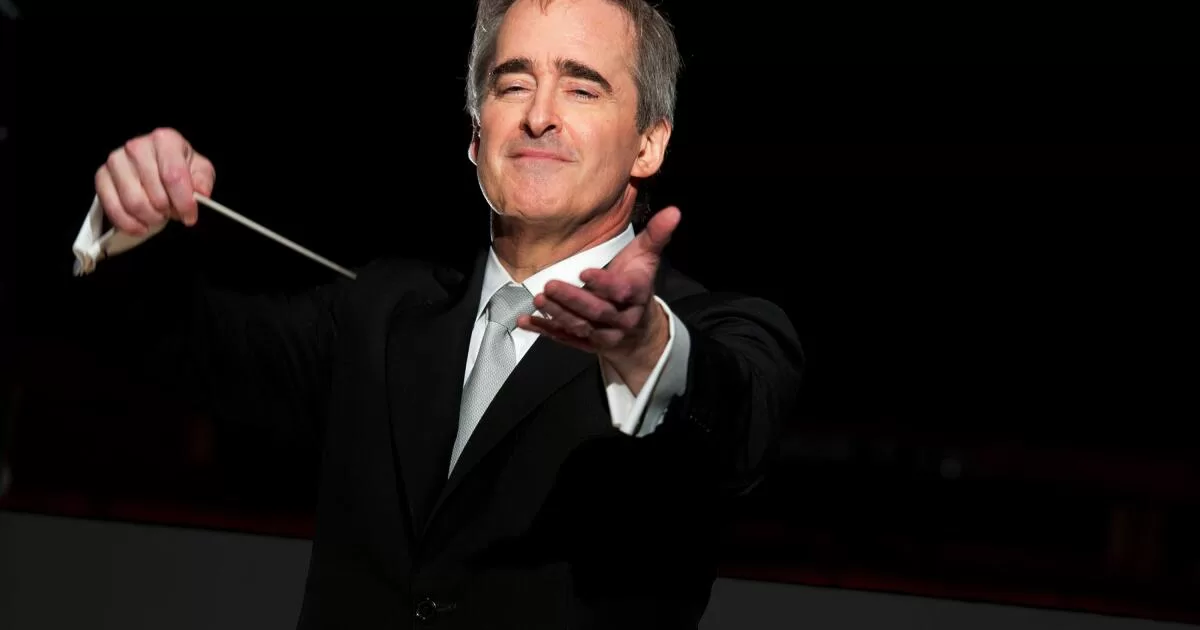

Conlon, 73, stresses that he’s not retiring and has no plans to stop conducting, “And, as you can tell from the appointment to laureate conductor, I’m not disappearing from L.A. Opera either.”

Educating young people about classical music and, most importantly, exposing them to the joys of it, remains one of Conlon’s most urgent callings. He grew up in the New York public school system, where he says he received a great musical education. Such an education, he believes, goes on to provide the basis for audiences going forward. When that education drops off — as it began to do for a variety of sociopolitical reasons in the 1980s — audiences begin to dwindle.

Today, Conlon says the situation has led to what he calls the “American paradox.” He says we probably have more great orchestras, conservatories and universities than any country in the world and are producing musicians at the highest level, yet musical organizations are “fighting to build and keep an audience.”

“We don’t have the demand we want,” says Conlon. “And as such, we’re called an elite art because we seem to be for fewer people. But it’s not an elite art. It’s for everyone.”

Conlon has displayed this sensibility over the years through his popular pre-show talks geared at educating and informing the audience in a relaxed, low-pressure way; as well as in the L.A. Opera performances that he has staged for free at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in downtown L.A.

“I like educating. So I want to continue education. Not in the formal sense. It’s possible, but I don’t think of myself as going to an institution as an educator,” Conlon says. “But I would like to do it through writing, through public speaking, through direct communication of that sort in order to stimulate and encourage and uninhibit people to come through the doors and give classical music a chance.”

Conlon has been a towering figure in classical music, both at home and internationally — with stints as principal conductor of the Paris Opera (1995-2004), general music director of the City of Cologne, Germany (1989-2002), music director of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra (1983-91) and principal conductor of the RAI National Symphony Orchestra. He has conducted more than 270 performances at the Metropolitan Opera since his 1976 debut there. He has also made appearances at major opera houses and festivals worldwide, including the Vienna State Opera, Salzburg Festival, La Scala, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Mariinsky Theatre, Covent Garden, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Teatro Real of Madrid, Teatro Comunale di Bologna and Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

During his tenure at L.A. Opera, Conlon has conducted 68 operas by 32 composers and presided over 460 performances to date, making him the most prolific leader in the company’s history. Career highlights include the company’s first Wagner “Ring” cycle; 2015’s “Figaro Trilogy” featuring John Corigliano’s “The Ghosts of Versailles,” Rossini’s “The Barber of Seville” and Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro”; and conducting a performance of “The Anonymous Lover” by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a prominent Black composer in 18th century France.

Conlon is also known for his devotion to his “Recovered Voices” initiative, which is dedicated to the performance of neglected or overlooked music by composers who were kept down by the Third Reich.

Conlon steered L.A. Opera through back-to-back turbulence, first in 2019 when general director Plácido Domingo resigned from the company amid allegations of sexual harassment after 16 years in that role; and a year later when COVID-19 ravaged live arts around the world, forcing the L.A. Opera stage at Dorothy Chandler Pavilion to go dark as the company canceled fall shows and projected losses up to $31 million.

“We’re living in difficult times and contentious times,” Conlon says, adding that the waters have smoothed significantly since the pandemic. “And so I believe that the constant availability of the arts, in whatever form — whether it’s museums or a symphony orchestra, whether it’s opera companies, whether it’s dance, or classical or modern ballet — I think that the classical arts have a stabilizing and humanizing influence on our society, and we need them.”

The arts are a privilege, says Conlon, but they are not just for privileged people. Art is for everybody, he says again. Because art is a spiritual force.